ON BORDERS

A theoretical research framework. Border as a working instrument for analysis and design

The notion of border signifies a limit condition, characterized by various meanings, layers and distinctions. Thresholds, boundaries and borders define the edges of everyday life and establish relationships between the built environment and communities. While the idea of border underlies a huge, multidisciplinary and complex domain of research, this text is briefly highlighting only some of the recent ideas on the concept of border, putting forth some different disciplinary perspectives for framing this topic. Based on some of the many foundational volumes that raise the border as a figure of theoretical analysis, the first part of the text focuses on various contemporary interpretations and typologies of borders, while the second will highlight the concept of border as a working instrument for analysis and design.

Intro. The recent study of borderlands phenomena

Currently, there is an intense debate surrounding the notion of borders, spanning many disciplines, making this a rapidly blossoming academic field. So called ”Border studies” appeared at the end of the XX century and most of the organisations, academic programmes and journals, associations and centers dedicated to this type of research date from the last three decades. The study of borders includes numerous disciplines, from political science and sociology to the arts, architecture and media. Therefore, the central perspective of the border studies is the interdisciplinary one, generating research approaches that appear to be important drivers of conceptual change, not only in planning and design. Recently, scholars had adopted the extended term “critical border studies” to reflect a fluid interpretation of what constitutes a border (Gritching and Zebich-Knos, 2017).

The concept of borders is an analytical tool and a reference point for cultural studies. At the same time, it became an attractive modus operandi because of its simultaneous material and metaphoric resonance. Border is frequently used as a geographical magnifier to study the evolution of society and tensions around topics like migration, colonialism, identity, conflicts, cross-border cooperation, globalization. Advantageously, the concept of border shifts in focus to peripheric contingent spaces, marked by precariousness and interdependency. This both inconsistent and fertile space incite cross encounters, favouring an unpredictable access to the unfamiliar and unexpected links, some scholars praising the hybridizing effects borders pose. The latent power and innovative possibilities of conflictual regions allow the challenging of the formal structures that enabled the socio-cultural and economic oppression. Moreover, the socio-political transformations of the beginning of the 21st century have added still further nuance to the concept of border. In the post-war period, European borders were challenged by globalisation and the emergence of the EU, both making borders irrelevant and replacing them with cohesive regions. Nevertheless, the recent wave of immigration into the EU and the on-going pandemic had the importance of national borders reinforced, raising the question on how to mediate borders through adaptation to existing contexts and growth.

Border research in European cultural studies increasingly focuses on the shifts in European identity. The social oppositions order the populations according to a dualistic logic, highlighting differences and creating numerous boundaries. Borders not only serve as instruments for conflict resolution, but also spatially distribute people and their interactions (Silberman, Till and Ward, 2012). In order to accommodate the deterritorialization of capital and wealth, the border’s traditional role changed in geopolitics. It is now more a process than a place. In this respect borders are mobile, following people around, expanding and “thickening”. (Rosas, 2006). Hence, borders can be found anywhere, transcending physicality and becoming portable, especially wherever poor, ethnic, immigrant, and/or minority communities collide with the leading society (Fox, 1994): their meaning ever changing with the people experiencing them.

The nature of borders

Borders are limits. From ancient times, by describing spaces through which relational systems of identity could be established, they offered groups and societies a sense of stability. The human need to draw lines functions as a cultural practice in its own right. Historically, borders materialised in walls have been justified to protect and regulate conflicts. A wall restrains mobility, interactions and exchange; yet it also establishes order by keeping people secured, protected and separated, tracing limitations between the private and public domains while also defining segregation patterns. The understanding of the many functions of borders is grounded in the cultural relationship to territory, which can change over time. During the Roman empire, “limes” were understood as transit zones, areas of contacts between diverse people. Only from the 19th century boundaries had become precise, measurable, both a physical and a legal topic in the Western world. Modern scholars have identified specific forms of bordering that affect not only a city’s structure and functional logic, but also the nature of urban experiences.To describe limits within the city that cut off and constrain neighborhoods, Jacobs coined the term ”border vacuum”. Instead of growth, these produce lifeless voids, dead-end city streets, vacancy and urban decay (Jacobs, 1961). In contrast, Lynch argues that boundaries can fuse communities together (Lynch, 1960).

The nature of borders can widely vary: they can be visible or invisible, law or custom, closed or opened, edgy or fluid borders. They can also be centres, not only peripheries; borders can be dividers, but also unifiers. The diversity of borders is to be understood through their collective imaginary and their potential: as a place of movement from one area to another, as a meeting point, as a possibility to experience the Other, as a social construct for negotiating identity, as instruments for shifting and focusing on the perimeter/periphery rather than the centre. Borders are generated by differences that are varying in influence and strength, so the borders become negotiable, even pliable, productive, rich in resources and, therefore, characterised by permeability and mutability.

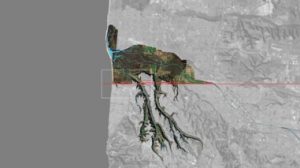

In this respect, borders are to be read always considering their spatial strategy of division (intra muros /extramuros), physical presence, social (racial and etnic including) impact, symbolic meaning, and, at a larger scale, geopolitical effect. Sometimes there are overlapping categories, like city walls, border zones, and migrating boundaries (Silberman, Till and Ward, 2012). There is great variety in the physical materialisations of national borders, from hard and violent to smooth, and even to ones too subtle to be easily noticed. Political borders are sometimes diffused, unclear and temporary. Sadly, some borders have saturated our daily headlines, like the US-Mexico one. In the wake of 11 September 2001, border technologies and policing were increasingly expanded. While border wall construction can be considered as a notably aggressive strategy, especially on the environment and on the affected local communities, they have become exceptionally popular with certain politicians throughout the last three decades.

The contradictory yet simultaneous functions of borders —to divide and connect, to exclude and include, to shield and constrain—are essential to all cultures. While mutable borders are a sign of life, closed borders signify social, ethnic or political division and often become quite violent. The hard demarcations also cut border peoples’ ability to coexist, cementing social differences on each side the longer they remain in place (Silberman, Till and Ward, 2012). The sealed borders cause hardened social edges to emerge: the reified borders along the Iron Curtain, the division between North and South Korea, the harsh realities of the Israeli-Palestinian and US-Mexico, but also less visible boundaries of the spatial residential segregation through the global spreading of gated, exclusive communities. These enclaves communicate widening social gaps and show the physical markers of social segregation, as gates, walls, highways, blocks of buildings or natural features, and land use zoning restrictions.

- fig 2

- fig 3

- fig 4

- fig 5

- fig 6

- fig 7

- fig 8

- fig 9

- fig 10

- fig11

- fig12

- fig13

- fig14

The concept of borders as a working instrument for analysis and design. Some relevant disciplinary perspectives

From the social perspective, Richard Senett questions today’s rupture between the built city and daily socio-cultural practices. Unpredictability, segregation, crookedness, contingency shape the relation between the city and its inhabitants and the fluctuation of borders and boundaries. Borders act as markers of inclusion and exclusion on different levels, and Senett brings in a distinction between the concepts of borders (porous) and boundaries (hard), discussing them as research instruments (to define public domain, relation between space and society, ground for potential commons etc.), also considering the way in which the border may be perceived to be a boundary/a line of exclusion in terms of communities, ethnicity, economy, everyday life etc. (Sennett, 2018). While concluding that ”the closed boundary dominates the modern city”, Senett brings in his plea for an open ethical city the possibility of the ”liminal edges’ ‘.

The anthropological perspective starts from the concept of borders in order to explore nowadays social conditions. All borders, Agier argues, are social constructs. These social constructs are amplified where territory, sovereignty and cultural identity overlap. Borders have acquired a new kind of centrality in the societies, becoming reference points for the growing numbers of people and raising the new topic of the border dweller, who is enclosed on the one hand and excluded on the other: today the experience of the unfamiliar is more common and the relation between self and other is in constant renewal (Agier, 2016).

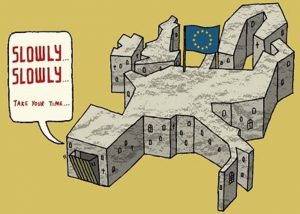

In 2007, urban geographer Mike Davis used the term “great wall of globalization” to describe the enclosed character of the newly globalizing world, one in which human movement was becoming increasingly stratified and dangerous, if not impossible, for migrants from the Global South (Gritching and Zebich-Knos, 2017). Before him, the term “gated globe” (Cunningham, 2004) was used to capture a similar dynamic. Lately, borders in the EU have become more porous, but the softening of borders among member states has been the progressive hardening of the external frontlines toward nonmembers, reflecting a mosaic of spatial practices and leading to what has been called “Fortress Europe”.

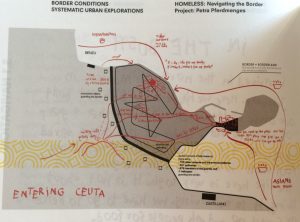

Until recently, borders have not attracted much researchers from the urban and architectural discipline. The first collective research steps outside the vastly apolitical space of professional design programmes to address a much neglected subject (Boddington and Cruz, 1999). Similar compendiums reappeared in the early 2000s, some emphasizing border as a working instrument in design practice. The global environment of precarity is a more recent focus of architectural scholarship: one of the first references is a 2017 MoMA exhibition, which drew attention to the physical environments globally experienced by refugees. Recently, some academic programmes are focusing on the spatial impact of borders, from conflict zones to marginal urban areas. The focus on border conditions is stated as an antidote to the predominant current of generic architecture determined by globalisation (Schoonderbeek, 2010). Borders are used as working instruments, focusing on local vectors such as identity, materiality, specificity; they present an intriguing situation that requires a selective and subjective multidisciplinary perspective. The border condition is a fertile ground for architecture, because there is still something left of a mystery, it is a vague territory to venture into, as vagueness is a form of tolerance that produces diversity (Schoonderbeek, 2010). The pioneers of the domaine, architect Teddy Cruz and political scientist Fonna Forman unfolded a twenty years research on the border, at the intersection of architecture, art, urbanization, borders, civic engagement and political theory, urging the intervention into the contested space between public and private interests, mediating interfaces between top-down and bottom-up urban dynamics, and designing political and civic processes to mobilize a new public imagination.

The social ecological perspective uses the concept of border in order to suggest hidden opportunities and to generate innovative approaches for softening hardened or conflicted borders. The environmental strategies in the form of conservation corridors, peace parks, transboundary protected areas etc. are robust, integrative approaches that encourage in-depth analysis of human–nature interactions during the policy-making process, enhancing exchanges and constructive interaction possibly leading to conflict resolution at the borders. Through direct interaction with ecosystems, using cleverly edge effects, some projects and visions were born (Gritching and Zebich-Knos, 2017).

Border Art is a contemporary practice rooted in socio-political experiences in borderlands. Emerging in the mid 1980’s, this artistic debate has assisted in the development of questions surrounding homeland, borders, surveillance, identity, race, ethnicity, and national origins. The spatial practices as cultural practices are artistically investigated, generating mappings of interference, in which the different boundaries take ephemeral shapes and various fusions become possible, fostering a new hope for the borderlands.

Image credits:

Fig. 1 – The national border at Triplex Confinium – the intersection of the national borders of Hungary, Serbia and Romania, https://turismistoric.ro/cum-arata-cel-mai-vestic-punct-al-romaniei-un-loc-simbolic-si-istoric-dar-care-poate-sa-iti-starneasca-fiori/ (Accesed: 14.10.2021).

Fig. 2 – The border trace the limitations between the private and public domains within the city fabric – Jimbolia (Photo: Irina Băncescu)

Fig. 3 – The permeable boundary fuse communities together – Via Zamboni, Bologna (Photo: Irina Băncescu)

Fig. 4 – The walls: from ancient times they offer a sense of stability by marking off a space through which to establish relations and identities – old city of Jerusalem (Photo: Irina Băncescu)

Fig. 5 – The Berlin wall (Photo: Irina Băncescu)

Fig. 6 – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bethlehem_Wall_Graffiti_-_Ich_bin_ein_Berliner.jpg

Fig. 7 – Improvised wall delimiting people with opposing social status, Berlin (Photo: Irina Băncescu)

Fig 8 – Liminal edges as described by Richard Sennett: Aldo van Eyck, playground Van Boetzelaerstraat, Amsterdam, (Photo: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01130/full)

Fig 9 – Mapping_ Border Conditions, Schoonderbeek, Marc (ed.), Border Conditions, Architectura & Natura Press, Delft, 2010

Fig 10 – Estudio Teddy Cruz + Fonna Forman, De-border 2020, 2020 (Photo: https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/at-the-border/358908/unwalling-citizenship)

Fig 11 – Fortress Europe (Photo: https://dafilms.com/program/388-keep_bangin_on_the_wall)

Fig. 12 – Demilitarized Zone between the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North) and the Republic of Korea (South), a significant ecological wildlife zone (Photo: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/130820-wildlife-korea-dmz-war-culture-biology-science)

Fig 13 – An installation by architecture studio Rael San Fratello, which connected children in the US and Mexico (Photo: https://www.dezeen.com/2021/01/19/design-of-the-year-2020-rael-san-fratello-border-seesaw/)

Fig 14 – Ecosystems and biodiversity, photo: Alejandro Prieto, 2021 (https://currentaffairs.adda247.com/alejandro-prieto-wins-bird-photographer-of-the-year-2021/)

Bibliography:

Agier, M. (2016) Borderlands. Towards an Anthropology of the Cosmopolitan Condition. Cambridge and Malden: Polity Press.

Boddington, A. and Cruz, T. (eds.) (1999) Architecture of the Borderlands. Architectural Design.

Brady, M. P. (2020) ”Border”, in Burgett, B. and Hendler, G. (eds.), Keywords for American Cultural Studies. 3rd edn. NY: NYU Press.

Cruz, T. and Forman, F. (2016) ”The Wall: the San Diego – Tijuana Border” in Artforum.

Fox, C. F. (1994) “The Portable Border. Site Specificity, Art and Representations at the U.S-Mexico Border” in Social Text 41. Duke University Press, pp. 61–82

Grichting, A. and Zebich-Knos, M. (eds.) (2017)The Social Ecology of Border Landscapes. Anthem Press.

Gržinić, M. (ed.) (2018) Border Thinking: Disassembling Histories of Racialized Violence. Viena: Sternberg Press.

van Houtum, H., Kramsch, O. and Zierhofer, W. (2005) B/ordering Space. UK: Aldershot.

Jacobs, J. (1961) “The Curse of Border Vacuums” in Death and Life of American Cities. NY: Random House.

Kolossov, V. and Scott, J. (2013) “Selected conceptual issues in border studies” in Belgeo 1.

Lynch, K. (1960) The Image of the City. Cambridge, Mass.: M.I.T. Press.

Mezzadra, S. and Neilson, B. (2013) Border as Method, or, the Multiplication of Labour. Duke University Press Books.

Pieris, A. (ed.) (2019) Architecture on the Borderline. Boundary Politics and Built Space .Architext, Routlege, Taylor and Francis.

Rael, R. and Cruz, T. (2017) Borderwall as Architecture: A Manifesto for the U.S.-Mexico Boundary. University of California Press.

Rosas, G. (2006) “The Thickening Borderlands: Diffused Exceptionality and ‘Immigrant’ Social Struggles during the ‘War on Terror’” in Cultural Dynamics 18, pp. 335-49.

Schoonderbeek, M. (ed.) (2010) Border Conditions. Delft: Architectura & Natura Press.

Senett, R. (2018) Building and Dwelling. Ethics for the City. New York: Allen Lane.

Silberman, M., Till, K. E. and Ward, J. (ed.) (2012) Walls, Borders, Boundaries. Spatial and Cultural Practices in Europe. Spektrum: Publications of the German Studies Association/ Berghahn Books.

TEXT: Irina Băncescu (UAUIM)

The above text captures some of the main ideas debated in the lecture held by Irina Băncescu during our LTT1.

Read more similar articles in our LTT1 Digital Publication linked below: