O1.M1.05. On borders: a theoretical research framework. Border as a working instrument for analysis and design

Free

About this course

Chapter 1. The study of borderlands phenomena

Teaching method: introductory lecture

Duration: 20 min

The notion of border signifies an edge condition, characterised by various meanings, layers and distinctions. Thresholds, boundaries and borders define the edges of our everyday life. Borders of all scales establish relationships between the built environment and surrounding communities.

While the idea of border underlies a huge, multidisciplinary and complex domain of research, with very many ramifications, this course is briefly highlighting only some of the recent ideas and theories on the concept of border, putting forth some different disciplinary perspectives for framing this topic. Based on some of the many foundational volumes that raise the border as a figure of theoretical analysis, the first part of the course will focus on the various contemporary definitions, interpretations and typologies of borders, while the second part will highlight the concept of border as a working instrument for analysis and design through relevant case studies.

There is an intense current debate surrounding borders in quite many disciplines, making it also a rapidly blossoming academic field. The so-called ”border studies” appeared since the end of the XX century and most of the organisations, academic programmes[1], academic journals[2], international associations[3] and centers for research date from the last three decades[4]. The study of borders now includes numerous disciplines, from political science and sociology to the arts, architecture and media. Therefore, the central perspective of the border studies is the interdisciplinary one, generating emerging research approaches that are innovative and appear to be important drivers of conceptual change, not only in planning and design.

In recent years, scholars had adopted the extended term “critical border studies” to reflect a fluid interpretation of what constitutes a border[5]. The critical ”border thinking”, attributed to Gloria Anzaldúa[6], describes the lived experiences of those who have been excluded from the production of modernity and, conditioned by decolonisation, promotes perspectives that speak back to political oppression.

The concept of border is an analytical tool and a reference point for cultural studies. At the same time, it became an attractive modus operandi because it has simultaneous material and metaphoric resonances.

Border is frequently used as a geographical lens through which one can study the evolution of society and tensions around issues like migration, place-making, colonialism, identity, conflicts, cross-border cooperation and globalization. The concept of border presents the advantage of a shift in focus to peripheral zones which contain contingent spaces, marked both by precariousness and interdependency. The border’s both inconsistent and fertile space incite cross encounters, favouring an unpredictable access to the unfamiliar, thus discovering unexpected connections. The consideration of the culture of a region from an alternative perspective of heterogeneity, messiness, contingency generates a lot of conceptual possibilities contained in the metaphors of borders, border crossings and borderlands, some scholars or artists celebrating in the hybridizing effects of borders. The latent power and innovative possibilities of conflictual regions allow the challenging of the formal structures that enabled the social, cultural and economic oppression.

Moreover, the sociopolitical transformations of the beginning of the XXI century have added still further nuances to the concept of border, as it is the case of the national borders in EU, which opposes characteristics as fluid and shifting versus rigid and static. In the post-war period, European borders were challenged by two key phenomena: globalisation and the emergence of the EU, both making them irrelevant and replacing them with cohesive border regions. Nevertheless, the recent massive wave of immigration into EU, the on-going pandemic period and the recent war in Ukraine had the importance of national borders reinforced. Therefore, one research question might be how to mediate borders through adaptation to existing contexts and growth, also considering “the border zones as laboratories for rethinking global citizenship”[7].

Border research in European cultural studies increasingly focuses on the shifts in European identity. New terms are coined, like ”b/ordered spaces”[8], a research term introduced to discuss the practices of identity formation in a global—and apparently borderless—world. The social oppositions order the populations according to a dualistic logic, categorizing difference and creating more and more boundaries. These social orders and structures not only serve as instruments for conflict resolution, but also distribute people and their interactions ex. wall-building delineates and demarcates space and controls peoples, things, and activities that are labeled as either belonging to or excluded from that space[9].

The border as the “open wound” invoked in the late 1980s by Anzaldúa no longer exists in this state, but in a mobile one, following people around – the border has expanded, had “thickened”[10]. In order to accommodate the deterritorialization of capital and wealth, the border’s traditional role changed in geopolitics, and the border is now more a process than a place. Hence conceptually speaking, borders, as discussed by Claire Fox, can be found anywhere; borders transcend physicality and become portable, especially wherever poor, ethnic, immigrant, and/or minority communities collide with hegemonic society[11]. The meaning of border changes with the people that experience them.

Chapter 2. The nature of borders

Teaching method: lecture, case study

Duration: 30 min

Borders are limits: from ancient times they offer a sense of stability by marking off a space through which to establish relational systems of identity. The human need to draw lines functions as a cultural practice in its own right, for example, in constructing the walls of his own house. But walls not only divide, they also bind. The mere existence of a wall embeds the idea of the existing other side of the wall line, bringing in various social meanings in time.

The nature of borders can widely vary: they can be visible or invisible, law or custom, closed or opened, edgy or fluid borders. They can also be centres, not only peripheries; borders can be dividers, but also unifiers. There are diverse types of borders (infrastructural, geographical, topographical, historical, architectural, social, cultural etc.) that are to be understood through their collective imaginary and their potential: as a place of movement from one area to another, as a meeting point, as a possibility to experience the Other, as a social construction for negotiating identity, as instruments for shifting and focusing on the perimeter/periphery rather than the centre. Borders are generated by differences (physical, legal, political, geographical, social, cultural, economic, symbolic etc.) that are varying in influence and strength, so the borders become negotiable, even pliable, productive, rich in resources and, therefore, characterised by permeability and mutability.

Historically, borders materialised in walls have been justified to protect and to regulate conflicts. A wall restrains mobility, interactions and exchange; yet it also establishes order by keeping people secured, protected and separated. Of course, walls are used to fortify and protect the city or parts of its quarters, but they also trace the limitations between the private and public domains within the city fabric. Walls can express the existence of conflicts of various kinds; they also divide, categorize and control the urban populations, defining segregation patterns.

Our understanding of the functions of borders is grounded in our cultural relationship to territory, which can change over time. During the Roman empire, borders or “limes” were not understood as boundary lines, but as transit zones, a collections of areas of contacts between different heterogeneous people. Only from the XIX century boundaries had become precise, measurable, both a physical and a legal topic in the Western world.

Scholars have identified specific forms of dividing and bordering that affect not only a city’s structure and functioning, but also the nature of urban experiences and, thus, the urban condition itself. In 1961, Jane Jacobs was coining the term ”border vacuum”[12] to describe limits within the city that can cut off and constrain neighborhoods that would otherwise grow, producing lifeless voids, dead-end city streets, vacancy and urban decay. In contrast, in 1960 Kevin Lynch argues that boundaries can fuse communities together[13].

There is a great variety of physical materialisations of the national borders, from hard and violent to smooth, even too subtle to notice, to no materialisation at all. Sometimes, these political borders are diffused, unclear and temporary, as the barricades improvised by the Hong Kong pro-democracy protesters against the oppresive opposition of China-led government. Some borders became quite famous, like US-Mexico frontier, the more than frequent subject of news reports, daily in our lifes of news readers. In the wake of 11 September 2001, the border technologies and policing were increasingly fortified. Border wall construction is a notably aggressive strategy, nevertheless, hard, walled borders became quite popular in the last three decades[14]. Elisabeth Vallet is assessing the growing phenomenon of border walls around the world as an attempt to control transnational movements with a view to securitization of borders rooted in the need to control mobility and preserve national identities. She identifies and analyses seventy border barriers worldwide to protect national borders, compared with only about fifteen of them in 1990[15]. The factor driving governments to erect walls are not necessarily territorial disputes or the presence of civil war in a neighboring state, but the economic inequality that makes the border unstable, as is the case for US-Mexico. The contradictory function of borders could not be ignored: while global corporate elite celebrated this new world in which national borders appeared no longer to prohibit the movement of people and material, a lot of nations restricted the informal movements of poor people across national borders, as happened with the new border walls in Europe as anti-intrusion barriers against migrants[16].

The contradictory yet simultaneous functions of borders —to divide and connect, to exclude and include, to shield and constrain—are fundamental to all cultures. While mutable borders are a sign of life, closed borders signify ethnic or political division and often become quite violent. The hardened lines of demarcation also cut border people’s ability to coexist, while internal borders cement social differences on each side the longer they remain in place[17]. The sealed borders cause hardened social edges to emerge: the reified borders between the Eastern and Western Bloc, with Berlin wall the most famous edge, the division between North and South Korea, the harsh realities of the Israeli-Palestinian and US-Mexico barriers that divide worlds and generate conflict and violence.

Usually, national borders have often been perceived as dead zones, as peripheral regions separated from the nation’s “core”. In this sens, it would be useful an approach that pays attention to spatial and cultural practices that inform these architectures of separation and exclusion: borders are dynamic spaces of inhabitation that exceed those of the national or administrative body. Borders and boundaries are far from fixed, static entities; besides tales of domination and division, they encompass dynamic narratives of negociation, survival, adaptation, as well as possibilities of identity formation. The palestinian terraced gardens can be perceived as a form of resistance to colonialisation by Israel; they are the residual traces of a vanishing garden landscape which was and is under the threat of colonial fragmentation and deliberate destruction[18]. Thinking on the recent debate on the ethics of immigration, the borders may become symbolically activist markers that encourage people to assume “political responsibility for pursuit of a decent life” extending “beyond the borders” of individual countries[19].

Starting from philosopher Henri Lefebvre’s theory on the production of space, the borders can be understood as representations of space, as spaces of representation and as everyday spatial practices[20]. Borders as a dominating space represent the geopolitics, the top-down process where political space is ordered and administered. On the contrary, borders as spaces of representation are a dominated space, possible to change and appropriate, according to how people (inhabitants, users) live and feel about the place, through its association of symbols and signs, psychological attachments and memories, and also physical qualities of the social space. Borders as everyday spatial practices generate social cohesion and continuity. Berlin Wall encompasses all these perspectives, as it is both a real physical object, a metaphor for Cold War’s division of the world and a place where topics as memory and commemoration are individually addressed. Another example is Israeli West Bank barrier: although the wall is to be a temporary defense against Palestinian attacks, many see it as significant in terms of geopolitics, this is the future negotiations over Israel’s final borders. The Berlin wall serves as an ironically metaphor in this sense, as its after 1989 meaning of freedom hereby is denied. At the same time, on a daily basis, Palestinian communities continue living and cultivating the land right near the wall or go to work in Israeli territories through the numerous check points.

Reading walls, borders and boundaries is according to their spatial strategies, physical presences, racial impacts, symbolic functions, or geopolitical effects. Sometimes there are overlapping cathegories: city walls, border zones, and migrating boundaries[21].

The city walls have served not only to protect from outside, but also to separate from within, to segregate (ex. the Jewish ghetto in Renaissance Venice; the twentieth century’s trend in the US toward spatial residential segregation and suburbanization; the global spreading of purified, gated, exclusive communities etc.). These enclaves communicate widening income and social gaps and show the physical markers of social segregation, including gates, walls, highways, blocks of buildings or natural features, and land use zoning restrictions etc.

The urban walls might both bind and separate: the recent European national strategies of containment toward unwanted urban pockets of religious conflict or ethnic difference mean that certain groups of people are expected to disappear from the inner as well as outer urban map behind newly constructed barriers (ex. the recent non official wall-making policies applied on the poor Roma or immigrant communities in cities all over Europe). These physical walls, achieved at high economic and symbolic costs, are actually the expression of the mental walls already existing between rival groups of people.

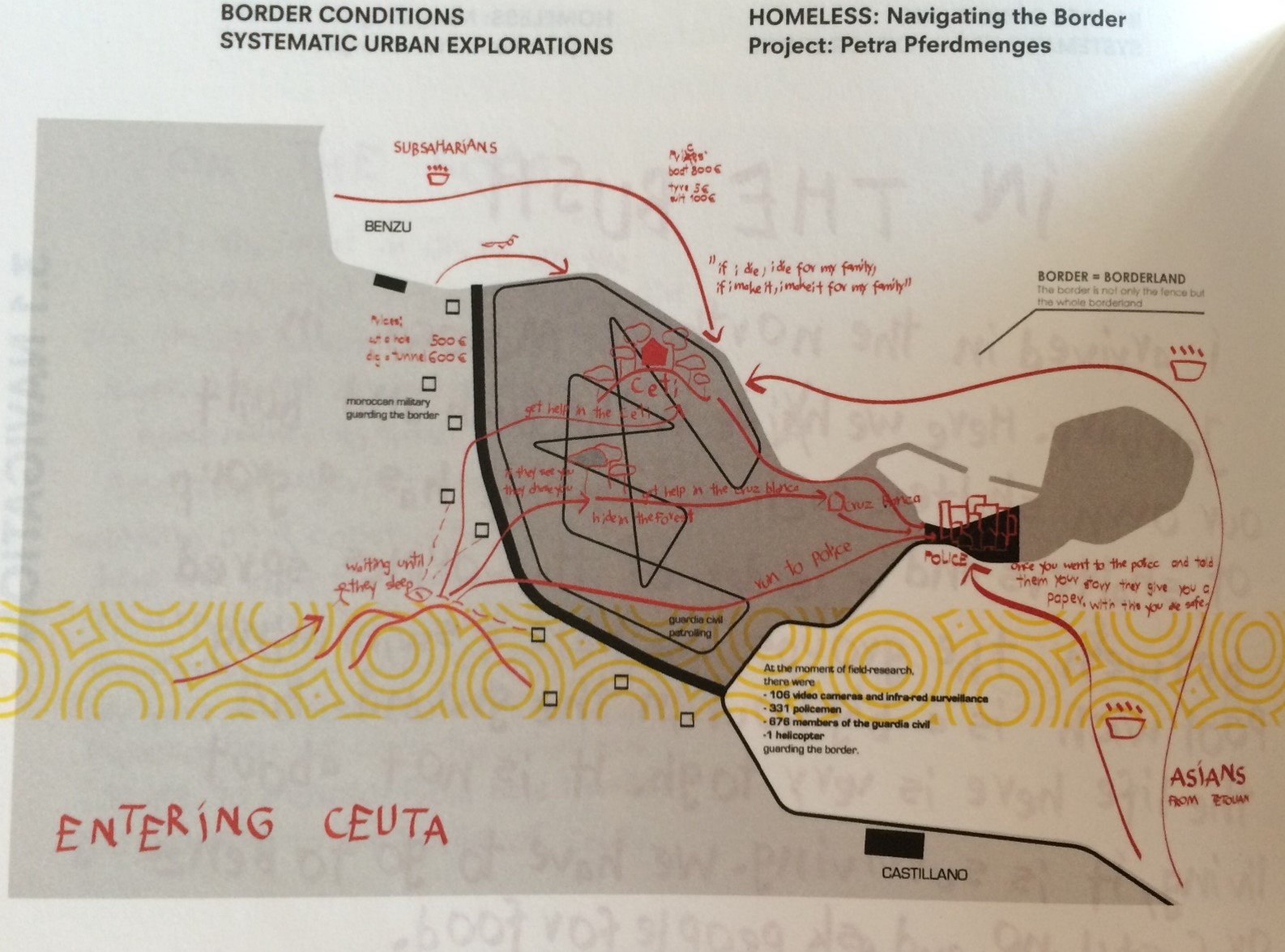

The situation when the external borders of the city have been walled against illegal immigration is well represented by the Spanish enclaves within Northern Africa. Here, buiding up a mechanism to protect the European border zone means that the hard borderline is more permeable to the circulation of goods and capital than to the movement of people. But, at the same time, the fence functions as a filter in both ways, there is the cross-border labor dynamics and social interaction typical of a border zone[22] (African traders and workers come to Ceuta, while the city’s inhabitants exit for lower prices for goods or a vacation house on the seashore in Morocco etc.). For the border zones, it is to be considered the sociocultural transformations and multiple historical layers in communities separated for decades (ex. the insular-like situation of West Berlin behind the Wall, the political divisions of the Cold War etc.).

In the light of the recent theory on multiculturalism in today’s Europe[23], communities negotiate the boundaries of established European democracies facing racism or migration and finding tactics of surviving exclusion and violence. The age of the “war on terrorism” and economic uncertainty made the governments and residents of receiving countries to respond to their migrants with increased surveillance and differentiated expectations of citizenship, creating the intangible migrating boundaries (ex. islamophobia etc.)[24] and hierarchies of exclusion.

Chapter 3. The concept of border as a working instrument for analysis and design. Some relevant disciplinary perspectives

Teaching method: lectures, case study

Duration: 40 min

Some social and geopolitical perspectives on the concept of border.

In 2007, Mike Davis used the term the “great wall of globalization” to describe the enclosed character of our newly globalizing world, one in which human movement was becoming increasingly stratified and dangerous, if not impossible, for migrants from the Global South[25]. Before him, the term “gated globe”[26] was used to capture a similar dynamic, arguing that international borders were playing the dual role of providing increased mobility for elites while denying mobility to the world’s most impoverished populations[27].

The border condition is to be discussed in the frame of today’s world, of our contemporary society, continuously transformed by the global capitalist economies with their increasing privatization of services and by the information revolution. This condition is defined so suggestive by the concept of ”liquid modernity”[28], a concept that embodies the shift from a hardware-focused world that is ordered, solid, stable, heavy to a software-based modernity where change and uncertainty are a permanence, a light, fluid, ever changing world. These changes of meaning in the human condition are to be investigated through the concepts of emancipation, individuality, time/space, work and community.

The concept of border in social theory works as an epistemic framework, as a method that enables new perspectives on the crisis and transformations of the nation-state, reconceptualizing issues of labor, migration, sovereignty, and governmentality. Far from creating a borderless world, contemporary globalization has generated a proliferation of borders[29].

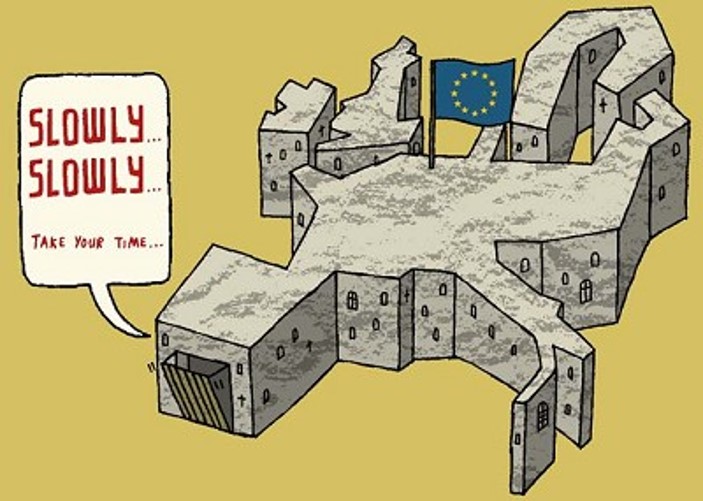

From a geopolitical perspective, borders among the EU member states have become more porous, and barriers to the flow of goods, capital and information have been increasingly lifted. But the softening of borders among EU member states has been the progressive hardening of the external frontlines toward nonmember states, leading to what has been called “Fortress Europe”[30]. These external borders reflect a mosaic of spatial practices (peace lines, fear walls, anti-immigration walls, and more liminal and invisible barriers like mutual prejudice and mistrust that aim to control the everyday forms of exchange and coexistence: the forecasted “borderless world” has indeed turned out to be a “gated globe.”

The anthropological perspective starts from the concept of border in order to explore nowadays social conditions. All borders, Agier argues, are social constructs. These social constructs are amplified where territory, sovereignty and cultural identity overlap. Borders have acquired a new kind of centrality in the societies, becoming reference points for the growing numbers of people and raising a new kind of topic, the border dweller, who is both inside and outside, enclosed on the one hand and excluded on the other: today the experience of the unfamiliar is more common and the relation between self and other is in constant renewal[31].

Working with impermanent contradictions: borders as research instruments for architecture and urban planning

From the social and urban perspective, Senett’s Building and Dwelling. Ethics for the City might be a manifesto for the XXI century cities, because its starting point is today’s rupture between the urban environment and daily social and cultural practices of its people, the fracture between the built and the lived. Throughout the book, he tries to answer the difficult question: ”Can ethics shape the design of the cities?”. Observing today’s urban processes, he highlights global phenomena as unpredictibility, segregation, crookedness, contingency, that directly shape the local reality, the relation between the city and its inhabitants and the fluctuation of borders and boundaries. Borders act as markers of inclusion and exclusion on different levels, and Senett brings in a distinction between the concepts of borders (porous, permeable, interactive) and boundaries (hard, limits which separate). ”The closed boundary dominates the modern city.”, he concludes. Senett brings positively in his plea for an open ethical city the concept of ”liminal edges”, referring to the experience of transition even if there is no clear barrier between the two entities. Aldo van Eyck’s playgrounds in post-war Amsterdam are such porous borders, liminal edges, ambiguous spaces that have an open function, merging with the city and stimulating street life and community spirit.

Borders and boundaries can be used as research instruments (ex. to define the public domain, the relation between space and society, as ground for potential commons of the people etc.), also considering the way in which the border may be perceived to be a boundary / a line of exclusion (in terms of communities, ethnicity, economy, everyday life etc.)[32].

Following the fall of the Berlin Wall and European unification, the related discourse was celebratory, praising flexible accumulation, fluid and borderless social mobilities and cosmopolitan identities, largely related to common values and globalisation. After the attacks in New York in 2001 and the age of terrorism, conditions in Europe and North America were linked to wars elsewhere—in the Balkans, Africa, the Middle East and Afghanistan. Surveillance was directed towards internal enemies, casting suspicion on culturally different minorities and migrant groups. These cultures of securitisation expanded to encompass socio-economic insecurities, particularly following the 2008 Global Economic Crisis[33].

Given this, until twenty years ago, borders have not attracted much researchers from the urban and architectural perspective. The first collective volume is ”Architecture of the Borderlands”[34], a special issue of Architectural Design, which covered urban peripheries, abandoned spaces, marginalized communities and vernacular buildings bringing together scholars as diverse as Teddy Cruz, Anuradha Mathur, James Corner, Paul Andreu, Manuel De Landa and Mike Davis. They made this effort to step outside the vastly apolitical space of professional design programmes to address a much neglected subject. Similar compendiums would appear again in the early 2000s, some being examples of tactical critique of border politics and emphasizing ‘border thinking’ as a design practice in sites of friction, many of them in the ”Global South”.

The general global environment of precarity is a more recent focus of architectural scholarship. One of the main references is the 2016–17 Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) exhibition, ”Insecurities: Tracing Displacement and Shelter”[35], which drew attention to the physical environments globally experienced by refugees. Public anxieties regarding refugee camps, detention environments and stateless populations have overtaken concerns regarding the social integration of minorities or migrants[36].

Starting from the state of liminality and transition that characterizes the border conditions and using the ”liquid modernity” concept coined by Zygmunt Bauman, Avermaete says that the contemporary architectural interest in border conditions starts from ”change as a permanent condition of human life”[37]. Therefore, recently, among the academic programmes that deal with the concept of border, the ”Borders & Territories”, a Masters programme at the Delft University of Technology, is focusing on the spatial impact of borders, from conflict zones to marginal urban areas. Umberto Barbieri asserts that the focus on border conditions might be an antidote to the predominant current of generic architecture determined by globalisation[38]. The borders perspective is inscribed in the contemporary tendencies from which to approach the architectural project, because borders are used as working instruments, focusing on local vectors such as identity, materiality, specificity. Moreover, borders present an intriguing situation that requires a selective and subjective multidisciplinary perspective. The bottom up analysis has a cultural significance, rendering visible, experiential and tangible the conflicts, complexities and contradictions present within the border territory. Barbieri finally states that the border condition is a fertile ground for architecture and urban planning, because there is still something left of a mystery, it is a vague territory to venture into, a vulnerable, but fertile condition, as vagueness is a form of tolerance that produces diversity.

The border seems problematic in the globalised world, obstructing global flows, contradictory to today’s nomadic society. Borders are associated with transgression, tension, spatial conflicts and contested spaces, with a direct impact on the city and territory, leaving lasting traces in the urban environment. There are more categories of border cities, the most dramatic situations being the divided cities (Berlin, Nicosia, Belfast) and the cities that are in close proximity with a contested national border or a continental divide (Gibraltar – Ceuta, San Diego – Tijuana)[39].

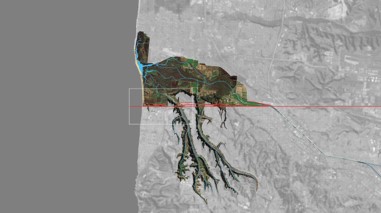

Whatever the situation, any researcher is forced to approach it using multidisciplinary directions in order to understand the specific reality of these areas. Architect Teddy Cruz and political scientist Fonna Forman unfolded an enduring research on the topic, at the intersection of architecture, art, urbanization, borders, civic engagement and political theory, urging the intervention into the contested space between public and private interests, mediating interfaces between top-down and bottom-up urban dynamics, and designing political and civic processes to mobilize a new public imagination. Their project “MEXUS” at the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale does not look at the U.S.-Mexico border as a dividing line, but as a region with a shared culture, economy and environment. This bio-region’s ecologies are shared between the two countries, highlighting the broader environmental issues the U.S. and Mexico face together. Moreover, in 2020 multi-layered border walls were built by the US, highlighting the “dramatic proximity of wealth and poverty” and the collisions between ecological and political priorities[40].

For architectural scholars, a relatively new field of critical heritage studies connected to borders has grown in scope and significance in the past three decades. It promotes theories of ”dissonant heritage”[41], starting from contested forms of cultural patrimony, sites where commemoration, territorial conflicts and cultural tourism intersect, specific objects and places that imply social conflict and are difficult to reconcile with normative histories (ex. Berlin Wall, sites of the Holocaust, places of refuge for immigrants near the borders etc.)[42].

Borders as core of complex environmental strategies

The social ecological perspective uses the concept of border in order to suggest opportunities for solutions that would otherwise not be apparent, and to generate innovative approaches for softening hardened or conflicted borders. The environmental strategies in the form of conservation corridors, peace parks, transboundary protected area etc. are robust, integrative approaches that encourage in-depth analysis of human–nature interactions during the policy-making process, enhancing exchanges and constructive interaction possibly leading to conflict resolution at the borders. Through direct interaction with nature and ecosystems, and with the intention of softening the hard borders, projects and visions were born, like the German Green Belt, the Korean DMZ Peace Park, the Cyprus GreenLine Scapes Laboratory and the Balkans Peace Park Initiative[43].

The edge effect is a concept that describes the influences two bordering communities have on one another in a transitional area, or ecotone. The edge effect can yield unexpected consequences, as it happens in the case of the Korean DMZ[44], where the security zone resulted in improved species conservation. In keeping with the edge effect, South Korea’s industrialization and overall development and North Korea’s deforestation contributed to the DMZ ecotone as the only place in both countries in which certain native species survive, in a so-called “gated ecology.” So, although it is the world’s most infamous borders, it is acknowledged as a significant ecological wildlife zone. These self-restored natural features and ecosystems now present the two countries with an opportunity to establish a transboundary conservation area[45], possibly as a catalyst to peace and reunification[46].

In contemporary topics of landscape planning and design, dynamic or unexpected natures have become increasingly recognized for their ecological value and for their contribution to the preservation of biodiversity. Marginal sites abandoned to nature—also referred to as terrain vague—have been described as ”third landscapes” (Gilles Clément). These neglected areas where biodiversity thrives can be considered the earth’s genetic reservoir. These ”third landscapes” can provide us with new social and ecological lenses that can be activated to reconceptualize border landscapes. In order for the border to develop and evolve and to become a backbone of reconciliation and interaction, the space not only has to be a social space of debate and negotiation, a cultural space of commemoration, but also an ecological space of evolving nature.

The landscapes of divided Berlin are such “shadow spaces,” terrains vague, no-man’s lands or interstitial spaces, as the shadows of the city, as the spaces of the possible, as spaces outside the mainstream official culture in which creation can take place. The linear landscape of the Berlin Wall, seven years after the fall of the Wall, revealed naturally evolving landscapes, the ”third landscapes” that Gilles Clément conceptualized around the same time. In the shadows of the more publicized and official Berlin Wall sites, some jewels of memory and pockets of wild landscapes have been salvaged from the rampant real estate ventures through the agencies of local ecological, artistic and spiritual communities ex. Mauer Park, the Lohmuehle Wagendorf (an ecological community of caravan dwellers who invested a segment of the former Wall, probably the most radically ecological and experimental space along the former Wall) etc.

Borderlands in conflict areas, while becoming negative, forsaken, forbidden and often highly militarized spaces, also become wildlands and havens for nature and biodiversity. In the absence of human development, nature can reclaim and restore its ecosystems and/or create new ones. In the contemporary fields of landscape design and planning, dynamic or unexpected natures have become increasingly recognized for their ecological and sustainable value and for their contribution to the preservation of biodiversity. The Cyprus Buffer Zone is of particular interest as a contemporary and transitioning boundary, as a marginal landscape and as a gateway to the European Union. Nevertheless, in the process of policy making and border management one has to take into account local needs and behaviors (ex. Palestine-Israel border) and to view border environments as part of a larger global community and not as an isolated ecosystem (ex. Tijuana Estuary)[47].

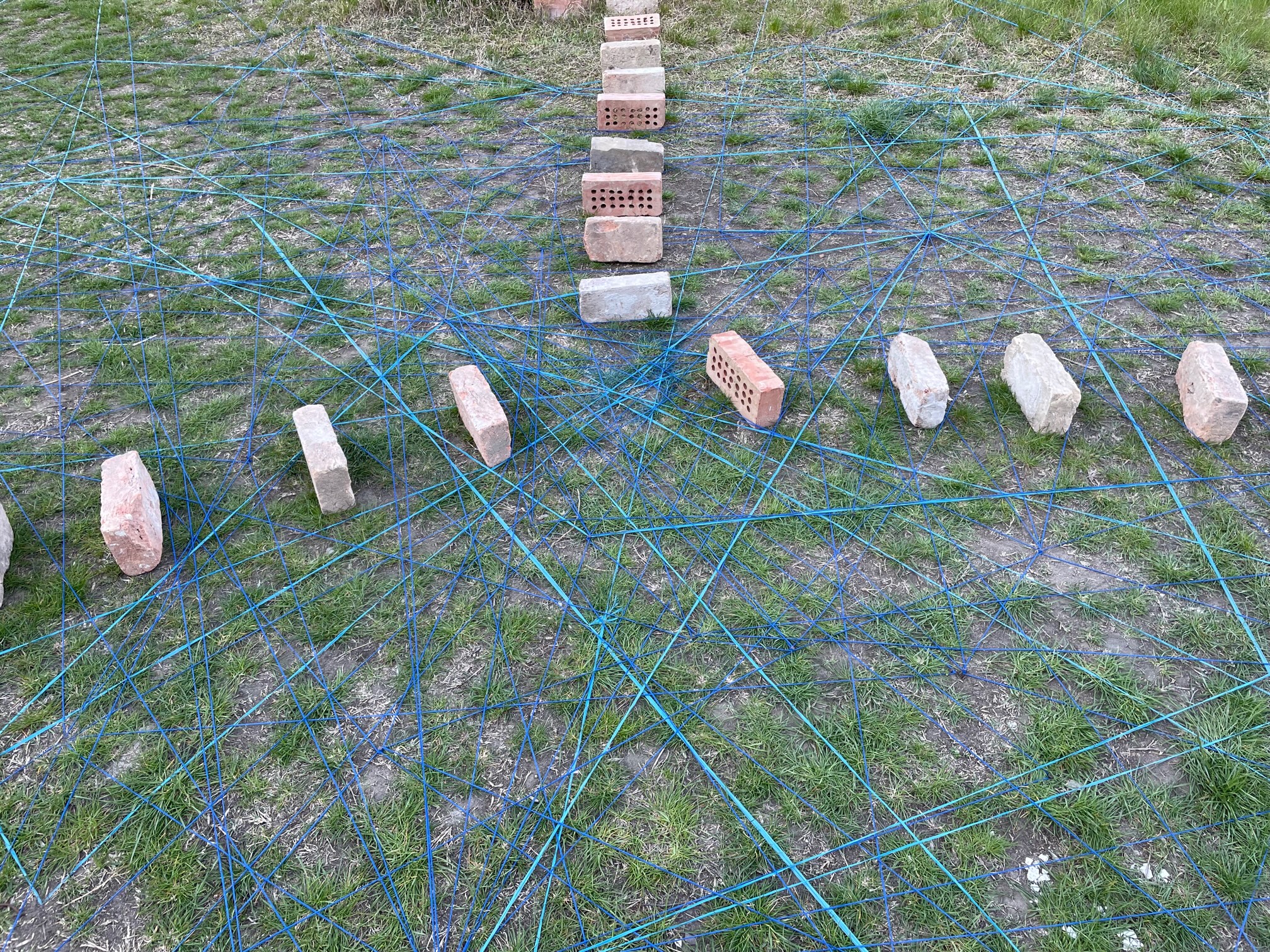

Border condition as the root of artistic research. Border Art

Finally, Border Art is a contemporary art practice rooted in socio-political experiences, such as those on the U.S.-Mexico borderlands. Since its conception in the mid 1980’s, this artistic practice has assisted in the development of questions surrounding homeland, borders, surveillance, identity, race, ethnicity, and national origins[48]. The spatial practices as cultural practices are artistically investigated, generating mappings of interference, in which the different boundaries take ephemeral shapes and various fusions become possible (ex. Border Art Workshop/Taller de Arte Fronterizo[49], the 2019 Seesaw installation in El Paso- Ciudad Juárez[50], 2019-2021 Oræ -Experiences on the Border[51]). In time, the landscape of exclusion of San Diego-Tijuana was transformed into a highly charged site for conceptual performance art.

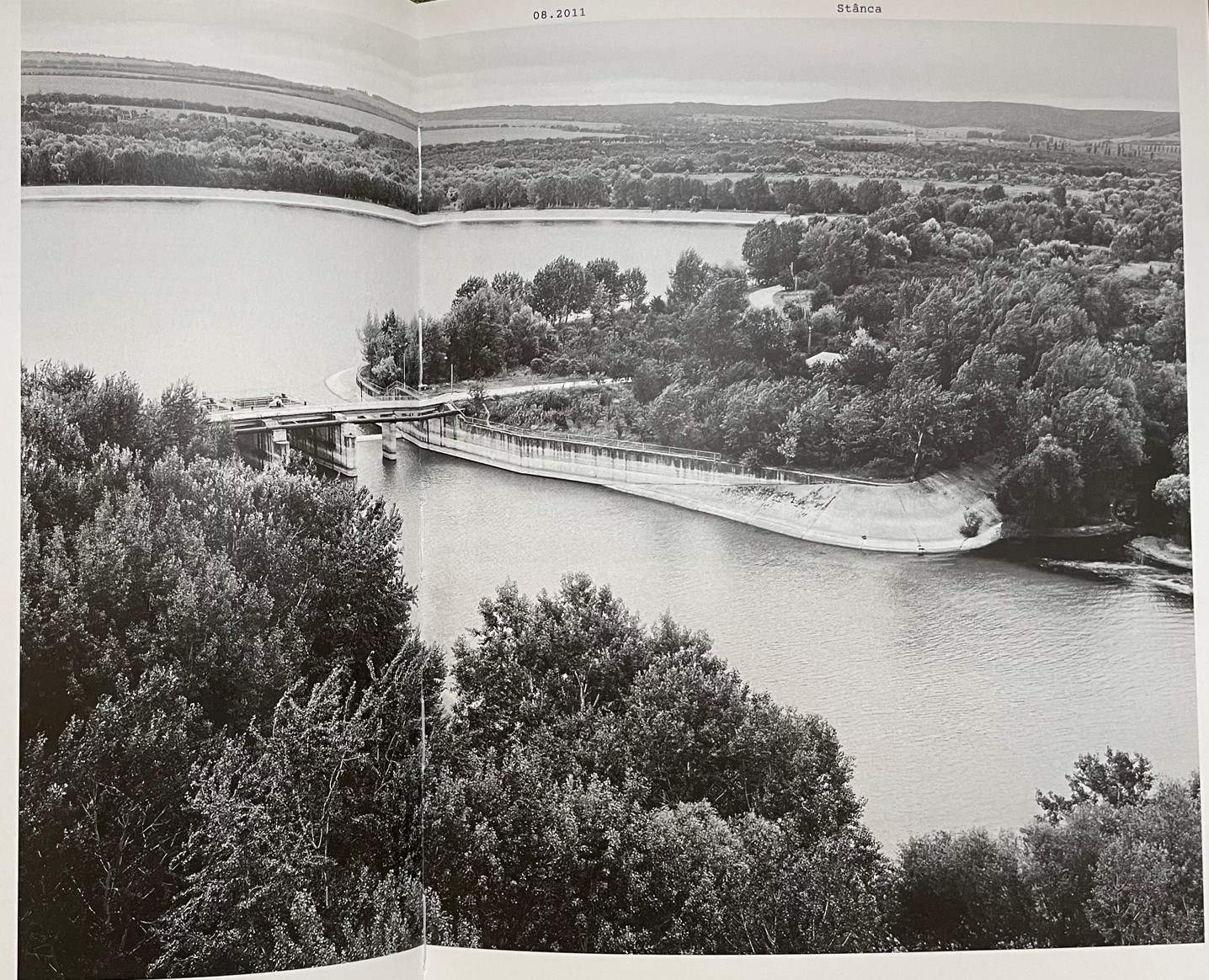

Artists Anca Benera and Arnold Estefan investigated different types of borders, artistically researching territories whose indistinct, hidden boundaries are produced by conflict and war, generating new geographical configurations in areas like Israel, Berlin or the oversea British territory[52]. Matei Bejenariu’s sensitive, artistic exploration of a constantly changing border zone at the limit of the European Union produced a documentary photography project that accurately encompasses the most recent socio-economic transformations of this area in-between Romania and Moldavia. Symbolised by the river Prut, the frontier is at the core of this artistic endeavour that sheds light on the specific local realities[53].

Chapter 4. Triplex Confinium. Border cities

Teaching method: lecture, case study

Duration: 10 min

How to read our Banat borders using all the above mentioned approaches? Moreover, how to assess the junction of these three national borders? Our Triplex Confinium is that point on Google Maps that you zoom in hoping that you will be able to glimpse a significant meaning or, at least, a sign of a spectacular form. The experience of the intersection of the borders of three countries is extremely rare. One cannot say he or she had really experienced it, as it is actually unreachable physically given the security conditions. It might be seen as the geographical coordinate on the map that seems illusive, unbelievable, still highly fascinating, emphasizing our abstract vision of the territory as ordinary map users. Yet this point is real and ordinary in its materiality, but also extremely symbolic for all three countries, as it becomes the symbol for an utopian vision of an ideal collaboration between those three countries.

The border conditions described in the chapters above are key instruments to be applied in the research of the cities like Jimbolia and Kikinda, oscillating around the intersection of the Romanian, Hungarian and Serbian borders, around the Triplex Confinium. Each method of research will trigger various results, but most of these results are to be surely tightly overlapped and interconnected, therefore should be considered from a transnational point of view. The network of all these places near the border is actually more intense and pulsating when you leave behind the abstract / territorial perspective and slide into the live micro narratives of the people living here, near the borders. As such, the Triplex Confinium states its symbolic status of an ideal collaborative transnational network in a state of constant renegociation.

[1] Ex. Borders & Territories is an architecture master programme at Delft University of Technology, https://www.borders-territories.space. [2] For example, Journal of Borderland Studies is one of the main references in this domain; it publishes research focusing on border issues, bordering dynamics and borderlands in an interdisciplinary perspective since its inception in 1986, https://www.tandfonline.com/toc/rjbs20/current. [3] The Association for Borderlands Studies (ABS) founded in 1976 includes academic, governmental institutions, and NGOs representing the world’s regions, https://absborderlands.org. [4] For a historiographical research charting the evolution of border studies, see: Vladimir Kolossov, “Theorizing Borders: Border Studies: Changing Perspectives and Theoretical Approaches,” Geopolitics 10, 2005, pp. 606–32; Corey Johnson, Reece Jones, Anssi Paasi, Louise Amoore, Alison Mountz, Mark Salter, and Chris Rumford, “Interventions on Rethinking ‘the Border’ in Border Studies”, Political Geography, 30, pp. 61–69, 2011. [5] Grichting, Anna, ”Social Ecologies and the Borderlands”, in Grichting, Anna, Zebich-Knos, Michele (ed.), The Social Ecology of Border Landscapes, The Anthem Series on International Environmental Policy and Agreements, Anthem Press, 2017, p.30. [6] Anzaldúa, Gloria, Borderlands / La Frontera: The New Mestiza (1987), 4th ed., Aunt Lute Books, 2012. In her book, Anzaldúa writes of the US-Mexico border as ”a third country—a border culture” (p. 3), a conceptual place from which to interrogate the centrality of the nation-state, its drive and values. [7] Cruz, Teddy, Forman, Fonna, ”The Wall: the San Diego – Tijuana Border”, Artforum, June 2016. [8] van Houtum, Henk, Kramsch, Olivier and Zierhofer, Wolfgang, B/ordering Space, Aldershot, UK, 2005. [9] Mattar, Daniela Vicherat, ” Did Walls Really Come Down? Contemporary B/ordering Walls in Europe”, in Silberman, Marc, Till, Karen E. and Ward, Janet (ed.), Walls, Borders, Boundaries. Spatial and Cultural Practices in Europe, Spektrum: Publications of the German Studies Association, Berghahn Books, 2012.[10] Rosas, Gilberto, “The Thickening Borderlands: Diffused Exceptionality and ‘Immigrant’ Social Struggles during the ‘War on Terror.’” Cultural Dynamics, no. 18, pp. 335-49, 2006. [11] Fox, Claire F., "The Portable Border. Site Specificity, Art and Representations at the U.S-Mexico Border", Social Text, no. 41, Duke University Press, pp. 61–82, 1994, https://doi.org/10.2307/466832. [12] ”Borders exert an influence (sucking) the life out of our cities and its neighborhoods. Not just literal walls and barriers, many features of urban life — from roads to parks to buildings — can cut off activities in public spaces and create what's called a border vacuum.”, Jane Jacobs, “The Curse of Border Vacuums”, Death and Life of American Cities, 1961. [13] “An edge may be more than simply a dominant barrier if some visual or motion penetration is allowed through it — if it is […] structured to some depth with the regions on either side. It then becomes a seam rather than a barrier, a line of exchange along which two areas are sewn together.”, Kevin Lynch, The Image of the City, M.I.T. Press., 1960. [14] Border walls: U.S.-Mexico, Israel-West Bank/Gaza, North and South Korea, Spain-Morocco, India-Pakistan, India-Bangladesh, Saudi Arabia-Iraq, Saudi Arabia-Yemen, Turkey-Iran, Iran-Pakistan, Iraq – Kuwait, Western Sahara: Moroccan Wall etc. [15] According to researcher Elisabeth Vallet, director of the Center for Geopolitical Studies at the University of Quebec-Montreal, ”Border Walls Aren't 'Fixing' Anything – But the World Is Building Them Anyway”, The Wire, 2017, https://thewire.in/external-affairs/border-walls-building-ineffective. [16] France – the Calais wall, Hungary – Serbia, Hungary – Croatia, Slovenia-Croatia, Austria-Slovenia, Macedonia-Greece, Bulgaria-Turkey, Greece-Turkey etc. [17] Silberman, Marc, Till, Karen E. and Ward, Janet (ed.), ”Walls, Borders, Boundaries. Introduction”, in Walls, Borders, Boundaries. Spatial and Cultural Practices in Europe, Spektrum: Publications of the German Studies Association, Berghahn Books, 2012. [18] Abusaada, Nadi, ” Palestine’s garden walls: the deliberate destruction of Palestine’s terraced gardens”, Architectural Review, February 2021, https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/palestines-garden-walls-the-deliberate-destruction-of-palestines-terraced-gardens. [19] Ibidem. [20] Silberman, Marc, Till, Karen E. and Ward, Janet (ed.), ”Walls, Borders, Boundaries. Introduction”, in Walls, Borders, Boundaries. Spatial and Cultural Practices in Europe, Spektrum: Publications of the German Studies Association, Berghahn Books, 2012. [21] Ibidem. [22] Ibidem. [23] Contrary to the idea to integrate into the host culture and belief systems, most migrants today maintain transnational ties across political borders, in Silberman, Marc, Till, Karen E. and Ward, Janet (ed.), ”Walls, Borders, Boundaries. Introduction”, in Walls, Borders, Boundaries. Spatial and Cultural Practices in Europe, Spektrum: Publications of the German Studies Association, Berghahn Books, 2012, location 532 on Kindle edition. [24] Ibidem. [25] Grichting, Anna, Zebich-Knos, Michele (ed.), The Social Ecology of Border Landscapes, The Anthem Series on International Environmental Policy and Agreements, Anthem Press, 2017. [26] Cunningham (2004) [27] The world can be roughly divided into two groups: the Functioning Core, characterized by economic interdependence, and the Non-Integrated Gap, characterized by unstable leadership and absence from international trade, Thomas P.M. Barnett, The Pentagon's New Map: War and Peace in the Twenty-First Century, 2004. [28] Bauman, Zygmunt, Liquid Modernity, Polity Press, Cambridge, 2000. [29] Mezzadra, Sandro and Neilson, Brett, Border as Method, or, the Multiplication of Labour, Duke University Press Books, 2013. [30] EU member states and the Schengen Area have raised almost 1000 Km of walls, which equals more than six Berlin walls, from the report "A Walled World, towards a Global Apartheid", published by Centre Delàs d'Estudis per la Pau, Transnational Institute, Stop Wapenhandel and Stop the Wall Campaign on november 2020, http://www.centredelas.org/mapamundoamurallado/. [31] Agier, Michel, Borderlands. Towards an Anthropology of the Cosmopolitan Condition, Polity, 2016. [32] Richard Senett, Building and Dwelling. Ethics for the City, Allen Lane, NY, 2018 [33] Pieris, Anoma (ed.), Architecture on the Borderline. Boundary Politics and Built Space, Architext, Routlege, Taylor and Francis, 2019. [34] Boddington, Anne, Cruz, Teddy (ed.), ”Architecture of the Borderlands”, Architectural Design, 1999. [35] https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1653. [36] Pieris, Anoma (ed.), Architecture on the Borderline. Boundary Politics and Built Space, Architext, Routlege, Taylor and Francis, 2019. [37] ”Contrary to the dominant trend of the first 200 years in modern times, today we no longer believe that a state of solidity may ever be reached. We are confronted with change as a permanent condition of human life. The limits and borders that define society are subject to constant renegociation, redefinition and alteration”, Avermaete, Tom, ”The Borders Within: Reflections upon Architecture’s Engagement with Urban Limens”, in Schoonderbeek, M. (ed.) (2010) Border Conditions. Delft: Architectura & Natura Press, p. 272. [38] Barbieri, Umberto, ”Introduction”, Schoonderbeek, Marc (ed.), Border Conditions, Architectura & Natura Press, Delft, 2010. [39] Schoonderbeek, Marc, ”Mapping Border Conditions”, Schoonderbeek, Marc (ed.), Border Conditions, Architectura & Natura Press, Delft, 2010. [40] ”The Tijuana-San Diego border region is a global laboratory for engaging the central challenges of urbanization today: deepening social and economic inequality, dramatic migratory shifts, urban informality, climate change, the thickening of border walls, and the decline of public thinking. We collect evidence of the porosity of this border, regardless of its intention as a top-down, political barrier. Borders cannot stop environmental, hydrological, viral, economic, normative, cultural, ethical, and aspirational flows. They cannot stop the winds that blow. These informal and often invisible circulations shape the transgressive, hybrid identities and urban practices of everyday life in border regions such as ours. In this era of escalating tension, militarization and racist political rhetoric, we offer counter-narratives of interdependence that reflect the cross-border flows and circulations of everyday life across the San Diego-Tijuana border.”, Estudio Teddy Cruz + Fonna Forman, De-border 2020, 2020, https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/at-the-border/358908/unwalling-citizenship. [41] Tunbridge and Ashworth 1996. [42] Pieris, Anoma (ed.), Architecture on the Borderline. Boundary Politics and Built Space, Architext, Routlege, Taylor and Francis, 2019. [43] Grichting, Anna, Zebich-Knos, Michele (ed.), The Social Ecology of Border Landscapes, The Anthem Series on International Environmental Policy and Agreements, Anthem Press, 2017. [44] The Demilitarized Zone, or DMZ, between the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North) and the Republic of Korea (South), is a strip of land that is comprised of two-kilometer strips of no-man’s land on either side of the boundary and in which there has been no human interference since 1953. [45] The transnational / transboundary conservation areas are established and managed by two or more countries, frequently being vehicles for peaceful cooperation (”peace parks”). An example is The European Green Belt – an initiative for nature conservation and sustainable development along the corridor of the former Iron Curtain. This unique cooperative network aimed at creating an “ecological backbone” across Europe and supporting communities in their effort to cooperate and conserve nature across national boundaries, https://www.europeangreenbelt.org. [46] Grichting, Anna, Zebich-Knos, Michele (ed.), The Social Ecology of Border Landscapes, The Anthem Series on International Environmental Policy and Agreements, Anthem Press, 2017. [47] Ibidem. [48] For example, the exhibition La Frontera/The Border: Art About the Mexico/United States Border Experience was a unique collaboration organized in 1993 between the Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego—a large mainstream museum—and the Centro Cultural de la Raza—a small community cultural center. As such, it countered the prevailing trend in the late-1980s and into the 1990s of major museums co-opting Chicano border art and turning “the border” into a strictly metaphoric, non-political concept. Though not exclusively comprised of Chicano/Latino artists, the La Frontera/The Border exhibition maintained the focus on the border as a geographical site and on its socio political reality, attempting at critical, collective effort between the two organizing entities, thus becoming a model for other institutions. [49] Fusco, Coco, ”The border art workshop/ taller de arte Fronterizo”, Third Text, 3:7, 53-76, 1989, DOI: 10.1080/09528828908576229 [50] An installation by architecture studio Rael San Fratello which connected children in the US and Mexico via a trio of seesaws slotted into the countries' border wall. The project was in place for only around 40 minutes in July of 2019, because it never received official permission and was designed to be assembled as quickly and covertly as possible in case border patrol were to intervene. Its goal is to foster a sense of unity at the divisive border, illustrating at the same time the cruelty and absurdity of the border wall. https://www.dezeen.com/2021/01/19/design-of-the-year-2020-rael-san-fratello-border-seesaw/ [51] The Swiss contribution to the 17th Venice Biennale is exploring the spatial and political dimension of the country’s border, putting the periphery at the centre and investigating the perception of border and the social implications of this inhabited territory. The team entrusted with the exhibition travelled along the Swiss border, meeting its inhabitants and inviting them to imagine a place of their choice at the frontier. The exhibition details a series of participative processes performed along the Swiss border that investigate the frontier and its inhabitants, revealing the poetic character of the space: “Little by little, relations replace measures, and references change. Certainties blur, and furtive memories creep in. Another map appears. Feelings and places, often ordinary, begin to resonate together, a new territory becomes possible” (Geneva-based team of architects and artists comprising Mounir Ayoub and Vanessa Lacaille, filmmaker Fabrice Aragno, sculptor Pierre Szczepanski), https://www.archdaily.com/960994/swiss-pavilion-at-the-2021-venice-biennale-explores-the-political-and-social-implications-of-the-countrys-border. [52] Benera, A. Estefan, S. (ed.) (2019) DEBRISPHERE - Landscape as an Extension of the Military Imagination. Bucharest: PUNCH. [53] Șerban, Alina (ed.), Matei Bejenariu: Prut, P+4 Publications, Bucharest, 2018.

References

- Agier, M. (2016) Borderlands. Towards an Anthropology of the Cosmopolitan Condition. Cambridge and Malden: Polity Press.

- Benera, A. Estefan, S. (ed.) (2019) DEBRISPHERE – Landscape as an Extension of the Military Imagination. Bucharest: PUNCH.

- Boddington, A. and Cruz, T. (eds.) (1999) Architecture of the Borderlands. Architectural Design.

- Brady, M. P. (2020) ”Border”, in Burgett, B. and Hendler, G. (eds.), Keywords for American Cultural Studies. 3rd edn. NY: NYU Press.

- Cruz, T. and Forman, F. (2016) ”The Wall: the San Diego – Tijuana Border” in Artforum.

- Fox, C. F. (1994) “The Portable Border. Site Specificity, Art and Representations at the U.S-Mexico Border” in Social Text 41. Duke University Press, pp. 61–82

- Grichting, A. and Zebich-Knos, M. (eds.) (2017)The Social Ecology of Border Landscapes. Anthem Press.

- Gržinić, M. (ed.) (2018) Border Thinking: Disassembling Histories of Racialized Violence. Viena: Sternberg Press.

- van Houtum, H., Kramsch, O. and Zierhofer, W. (2005) B/ordering Space. UK: Aldershot.

- Jacobs, J. (1961) “The Curse of Border Vacuums” in Death and Life of American Cities. NY: Random House.

- Kolossov, V. and Scott, J. (2013) “Selected conceptual issues in border studies” in Belgeo 1.

- Lynch, K. (1960) The Image of the City. Cambridge, Mass.: M.I.T. Press.

- Mezzadra, S. and Neilson, B. (2013) Border as Method, or, the Multiplication of Labour. Duke University Press Books.

- Pieris, A. (ed.) (2019) Architecture on the Borderline. Boundary Politics and Built Space .Architext, Routlege, Taylor and Francis.

- Rael, R. and Cruz, T. (2017) Borderwall as Architecture: A Manifesto for the U.S.-Mexico Boundary. University of California Press.

- Rosas, G. (2006) “The Thickening Borderlands: Diffused Exceptionality and ‘Immigrant’ Social Struggles during the ‘War on Terror’” in Cultural Dynamics 18, pp. 335-49.

- Schoonderbeek, M. (ed.) (2010) Border Conditions. Delft: Architectura & Natura Press.

- Senett, R. (2018) Building and Dwelling. Ethics for the City. New York: Allen Lane.

- Silberman, M., Till, K. E. and Ward, J. (ed.) (2012) Walls, Borders, Boundaries. Spatial and Cultural Practices in Europe. Spektrum: Publications of the German Studies Association/ Berghahn Books.

- Șerban, A. (ed.) (2018) Matei Bejenariu: Prut. Bucharest: P+4 Publications.

Other Instructors

Alexandru BELENYI

Researcher

Irina TULBURE

Assistant Professor

Irina BĂNCESCU

Assistant Professor

Ilinca PĂUN CONSTANTINESCU

Teaching Assistant

Cristian BORCAN

Teaching Assistant

Cristian BĂDESCU

Teaching Assistant

Syllabus

The aim of this class is to introduce students to the border studies, building up a varied and diverse theoretical research framework and showing how the concept of border can be applied as a working instrument for analysis and design. The first course of this class therefore concentrates in the first part on explaining how and why the borderlands phenomena became the focus of academic research, detailing the nature of borders through case studies. The second part of the first course investigates how the concept of border can be applied as an working instrument for analysis and design, detailing some relevant disciplinary perspectives that can be used in such direction. Numerous case studies back up this inquiry, including some from the regional sphere.

O1.M1 UNDERSTANDING THE TERRITORY AS A SYSTEM

O1.M1.05 On borders: a theoretical research framework. Border as a working instrument for analysis and design

Type of format

Lecture

Duration

50 min lecture (theoretical notions & case studies) 10 min break 50 min lecture (theoretical notions & case studies)

Possible connections (with other schools / presented topics)

UAUIM O1. M1.01 Grids. Formal tools for understanding and manipulating space UAUIM & FAUT O1. M1.04 Reinventing the grid: the thin line between relevance and oblivion BME O1. M3.02 History drawn in the landscape- Border imprints and how to read them - Working with the cultural landscape

Main purpose & objectives

The first course of this class concentrates on the following objectives: -introducing students to a wide palette of theoretical notions regarding border studies, border theory and border as an instrument / research method -analyzing the theoretical principles discussed in relation to their application within relevant international and national case studies The main purpose of this class is to help students understand and recognize the complexity and interdisciplinarity of the notion of border in today’s world. Border will be used as a concept for deciphering complex spatial and intangible phenomena that characterises the border zones. The edge condition, generated by differences, might be visible or invisible, law or custom, closed or opened etc. Borders are studied as territorial markings, as unifiers/dividers, as centers not only peripheries. The class introduces various perspectives by which students can research and understand the nature of the borders and their influence in the environment, by using recognised references and case studies. The first course of this class therefore concentrates on the following objectives: -introducing students to the basic notions around the concept of border and the up-to-date research in the domain of border studies -analyzing the theoretical principles in relation to their application, meaning and impact -understanding and recognizing the theoretical notions discussed using different case studies to illustrate each specific situation The learning methodology: extensive and diverse literature on the topic, case studies analysis, mapping, sensitive readings of research area, typology, index, comparative critical analysis etc.

Skills acquired

The course aims to build up knowledge and skills for critical thinking through the applied theory of the concept of border on various research areas. The border as a working instrument will be applied using different disciplinary perspectives with the aim of analysing an existing context and understanding the complex dynamics in progress in that area. Using a selection of relevant case studies, it is expected that students will be able to increase their ability to use the proposed instruments and methods, becoming more aware of their role as future architect-mediator and the impact of social, cultural, geopolitical factors on today’s built environment.

Contents and teaching methods

1. The study of borderlands phenomena Teaching method: introductory lecture 2. The nature of borders Teaching method: lecture, case studies 3. The concept of border as an working instrument for analysis and design. Some relevant disciplinary perspectives Teaching method: lecture, case studies 4. Triplex Confinium. Border cities Teaching method: lecture, case study

Reviews

Lorem Ipsn gravida nibh vel velit auctor aliquet. Aenean sollicitudin, lorem quis bibendum auci elit consequat ipsutis sem nibh id elit. Duis sed odio sit amet nibh vulputate cursus a sit amet mauris. Morbi accumsan ipsum velit. Nam nec tellus a odio tincidunt auctor a ornare odio. Sed non mauris vitae erat consequat auctor eu in elit.

Members

Lorem Ipsn gravida nibh vel velit auctor aliquet. Aenean sollicitudin, lorem quis bibendum auci elit consequat ipsutis sem nibh id elit. Duis sed odio sit amet nibh vulputate cursus a sit amet mauris. Morbi accumsan ipsum velit. Nam nec tellus a odio tincidunt auctor a ornare odio. Sed non mauris vitae erat consequat auctor eu in elit.