O1.M1.01. Grids, Formal tools for understanding and manipulating space

Free

About this course

Introduction¹

Teaching method: introductory lecture

Duration: 5 min

The following article is the base for a theory course on the evolution of gridded urban settlements.

The objectives of the course are:

-

- To offer a succinct timeline of the gridded settlement from the neolithic age to the present day. The timeline focuses on the emergence of a conceptual global gridded space during the 15th century and describes Thomas Jefferson’s Land Ordinance Act of 1784 as probably the most ambitious and direct materializations of this space. (Section 1 – The Emergence of a Gridded World)

-

- To provide a basic framework for understanding the emergence of the idea of a global grid by looking at its 15th century origins. This is achieved by analyzing Irwin Panofsky’s view on the qualities of linear perspective and Marshall Mcluhan’s global visual space created through the agency of the printing press. Both these inventions are understood as vehicles for the spread of a homogenous, all encompassing field of relations and cultural production. (Section 2 – The Ethos of the Gridded World). Apart from analyzing interpretations and qualities of gridded space the section also presents a hypothesis of what it means to be „off grid” – qualities of an alternative urban reality.

-

- To look at the current state of development of the gridded world and the switch between an open, almost infinite grid, conceptually enveloping the planet characteristic of the industrial revolution, to the implosion of this grid, into the “ladder” – a spine like structure creating ever smaller, disconnected and controllable urban enclaves. The last section also looks at strategies proposed by urban planners and landscape artists for acting upon gridded settlements and their surroundings. (Section 3 – The Grid and the Contemporary Urban Environment)

Instead of focusing on the local history of Banat, the course offers an understanding of the general ethos that emerged in the fifteenth century, with Banat being also a reflection of that context. The course also relies on information offered by other courses[2] within the overall curricula to supply the local details of the evolution of the Banat region.

The emergence of a gridded world

Teaching method: lecture, case study

Duration: 20 min

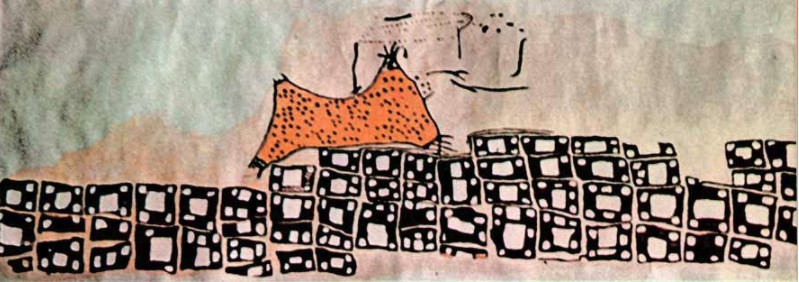

Orthogonal patterns have been linked to the organization and structure of settlements almost from the beginning of sedentary urban space[3]. First it is worth mentioning the proto orthogonal city of Catal Huyuk (cca. 7500 BC) both for its orthogonal layout and for the city map discovered on one of the walls that displays an orthogonal pattern made of individual units[4] (Figure 1). According to architectural historian Pier Vittorio Aureli the switch from circular houses to orthogonal units[5] is the moment when the urban environment became preoccupied with storage of surplus and private ownership. The orthogonal housing pattern gradually developed into a gridded settlement where urban islands would be laid down with the help of basic geometry. Gridiron cities were also built during classical antiquity. Important examples are Piraeus, Miletus, Olynthus, Agrigentum, Paestum, Alexandria that appeared between 5th-3rd centuries BC[6], with the first two lied out by Hippodamus of Miletus – thus the term Hippodamic plan.From the beginning the evolution of the grid has been linked to private property and economic functions or growth[7] but at the same time, the grid has always been linked to an idea of unity of the urban environment[8]. During the evolution of the Roman Empire, the gridded settlement was used for colonizing new territories and for creating a homogeneous network of settlements. Several thousands new cities were established by the Romans, mostly on the edges of the Mediterranean Sea[9]. However, during the Middle Ages, the grid plan suffered fall back from use, probably due to the need for more permanent fortifications.

However the objective of the paper is not a precise history of grids but rather to reflect on the ethos of an emerging gridded world in the 15th century and to track down its current state of development and provide several concepts for both deciphering and working with gridded settlements or urban grids in general.

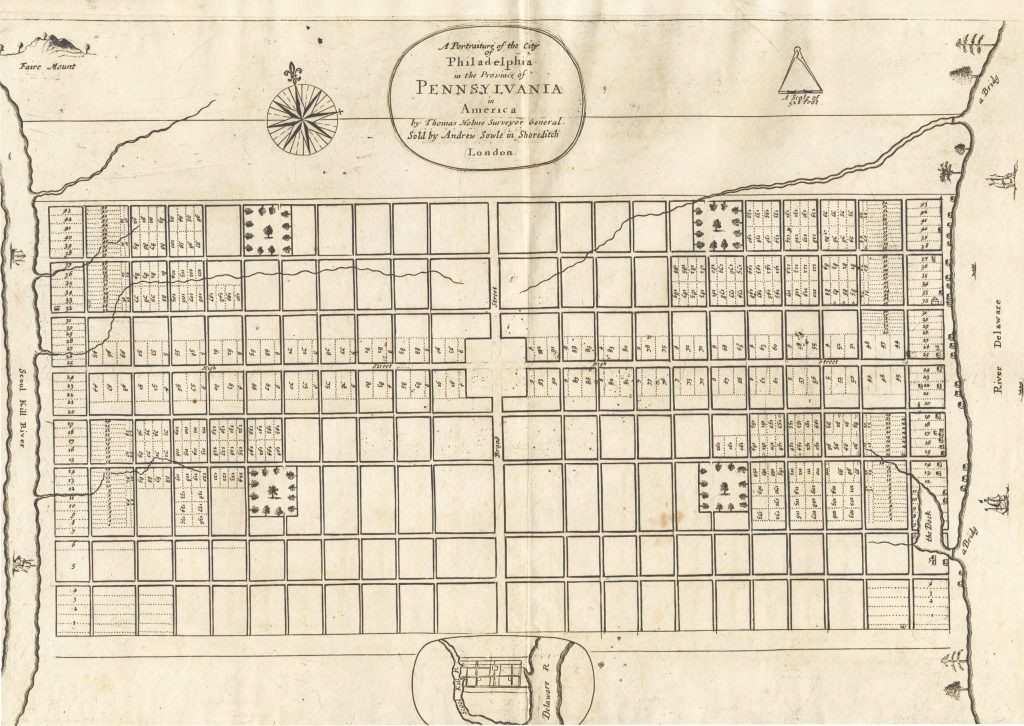

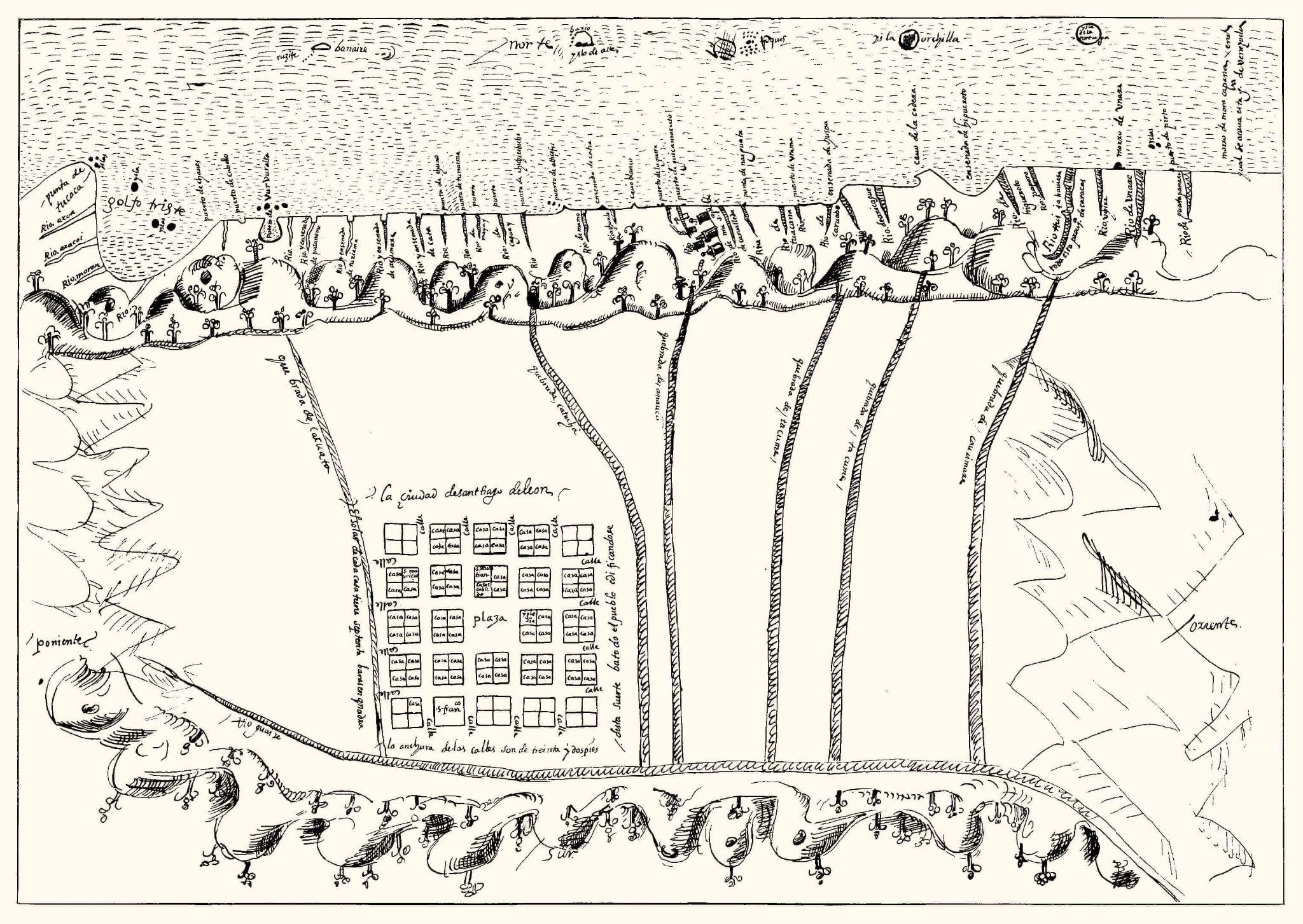

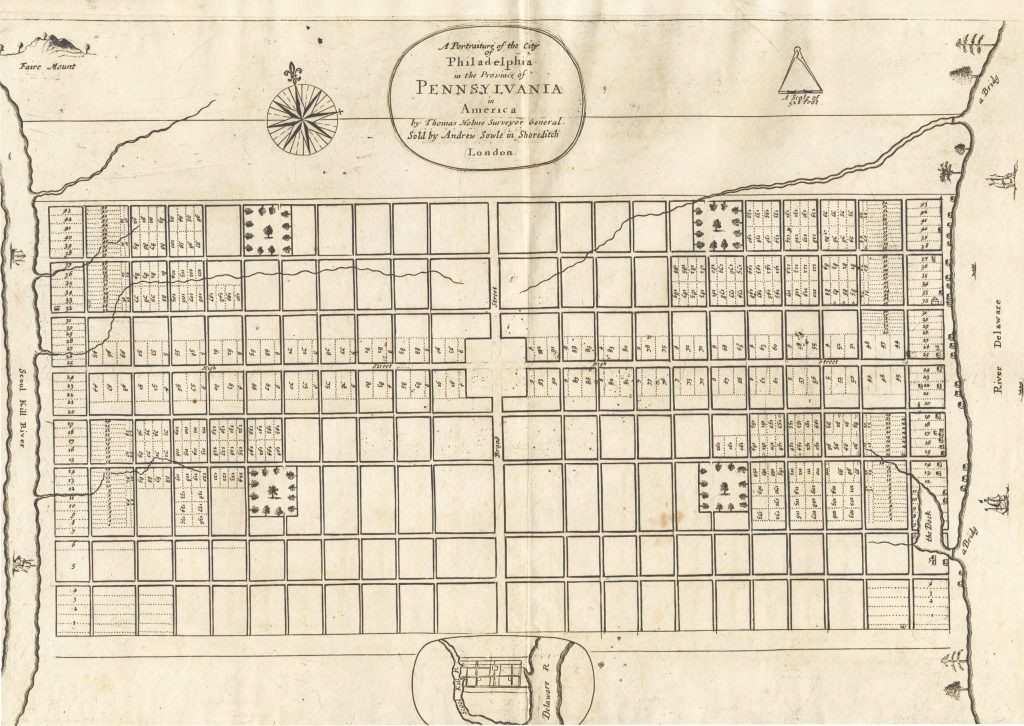

Starting with the 15th century grids were brought back into use but this time benefitting from the advancement in geometry and mathematics of the Middle Ages. Grids became the main tools for the internal colonization of Europe[10] through new cities established on private land, with Banat being one such example, but also for the newly discovered continents (Figure 2). Examples of gridded cities during the 16th and 17th centuries, in Europe and especially in North and South America are more than numerous and one is inclined to ask whether gridded cities were the main form of urban expansion, at least in territories occupied by the western world?

The proliferation of grids is clearly related to their military, organizational and economical benefits and there is ample analysis regarding the connection of grids and the development of private property. As architecture historian Maria S. Gudicci explains even the apparition of perspective and the perspectival grid can be related to funciary interest and the widespread apparition of abaco schools during the Middle Ages[11].

By the 18th century grids and gridded space had extended to engulf more and more of the territory up to the point where it was conceivable to apply the notion of the grid to large national territories.

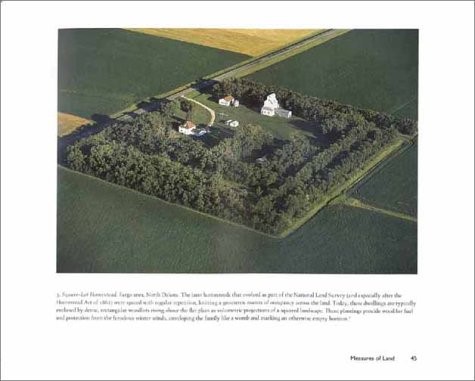

However, this perspective does not turn grids into exclusively capitalist spatial instruments. In order to better understand the spatial spread of the gridded plain we will turn to probably the largest act of territorial colonization and one of the most direct juxtaposition of an undifferentiated grid onto a natural landscape – Thomas Jefferson’s Land Ordinance of 1784. Thomas Jefferson’s ordinance is concomitant with the realization of the Banat productive landscape and it reflects the larger image of a phenomenon and cultural ethos that also encompases developments such as the productive landscape of Banat. The ordinance introduced a division of the United States’ territory based on townships, each comprising 36 x 1 square mile sections. Quite soon after Jefferson’s proposal a large state apparatus was set in motion to enact this conception of the national territory. At its edges the machinery for land occupation was avid for expansion and for conquering new territories while towards its core it gradually became a tool for organizing social programs, like education, through such principles as section 16 of each township being assigned to education facilities.[12]

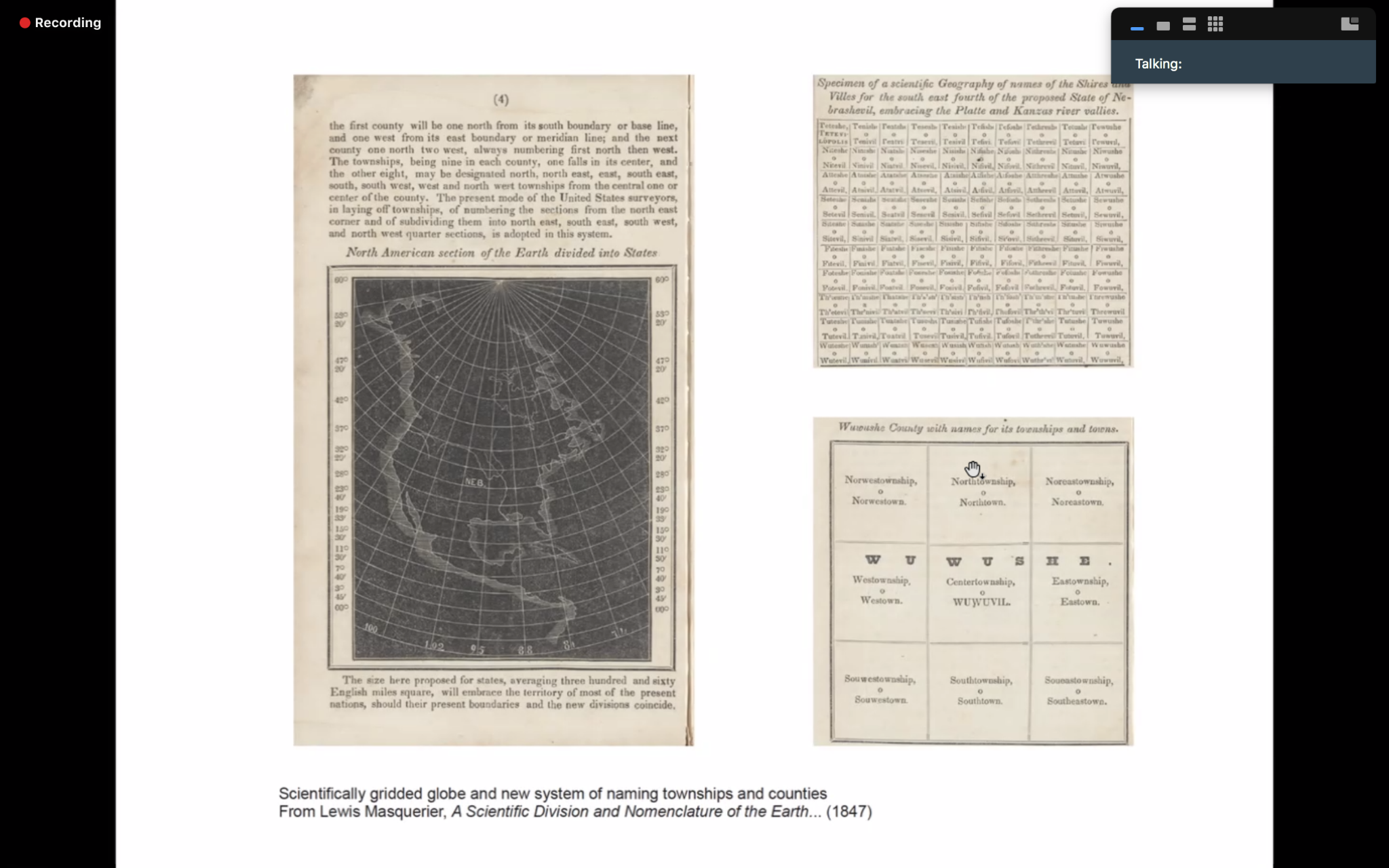

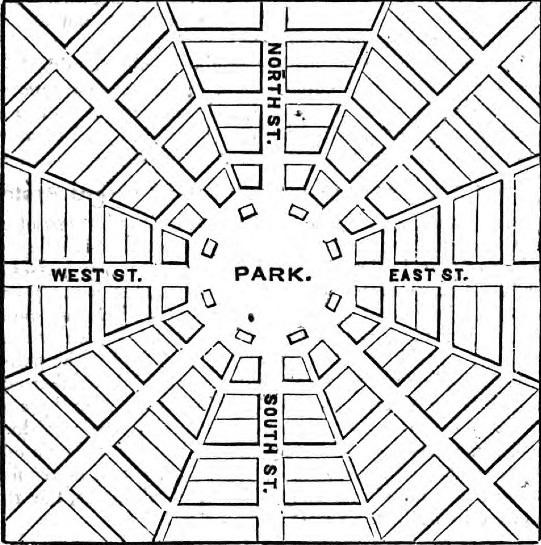

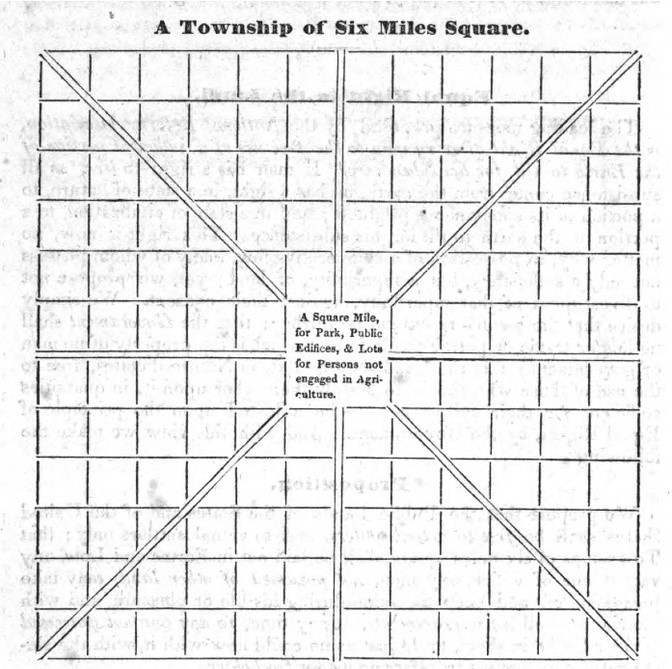

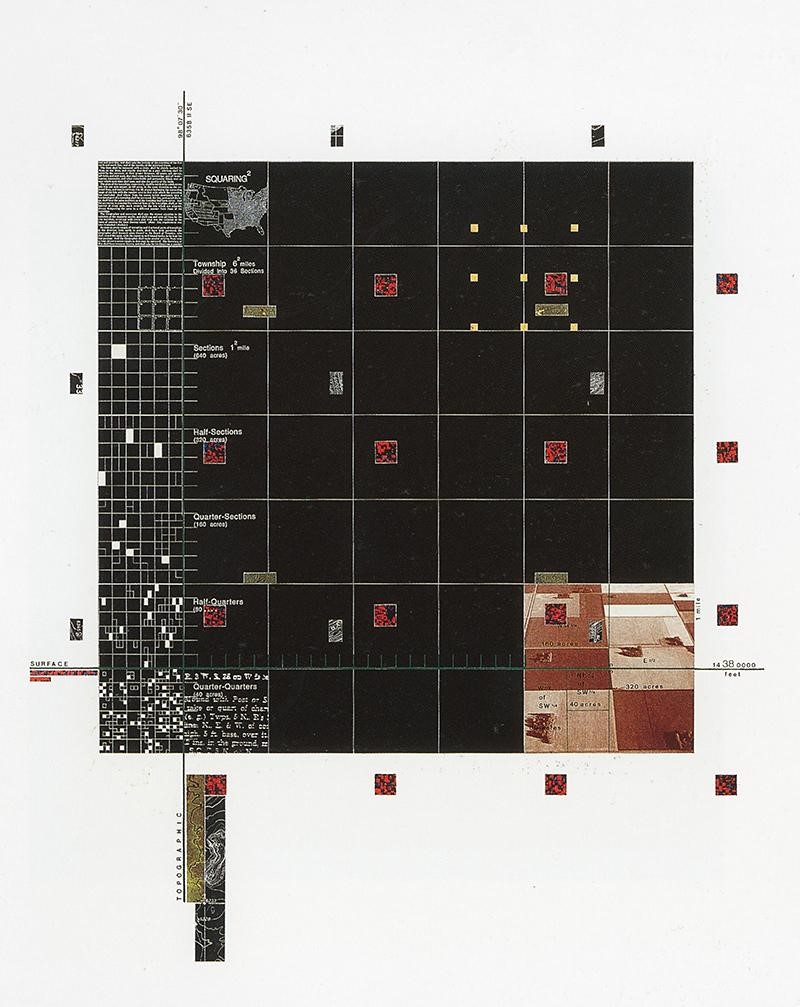

Further illustration of the ethos of the emergent gridded world is Lewis Masquerier, A Scientific Division and Nomenclature of the Earth (Figure 3) that displays North America as a fully gridded and indexed territory. Masquerier was part of a second group of land reformers – The National Reform Association that worked to further define Jefferson’s original vision. As such they also proposed more detailed plans for the organization of democratic townships where the equal, symmetrical, uniform distribution of a grid like structure was understood as a tool for democratic society[13] or New England township democracy as it is usually referred to (Figure 4) and not a tool for avid economic enlargement as it was used during high colonial times. In fact we suggest that grids became a spatial framework against which the political direction of policies or laws became clear.

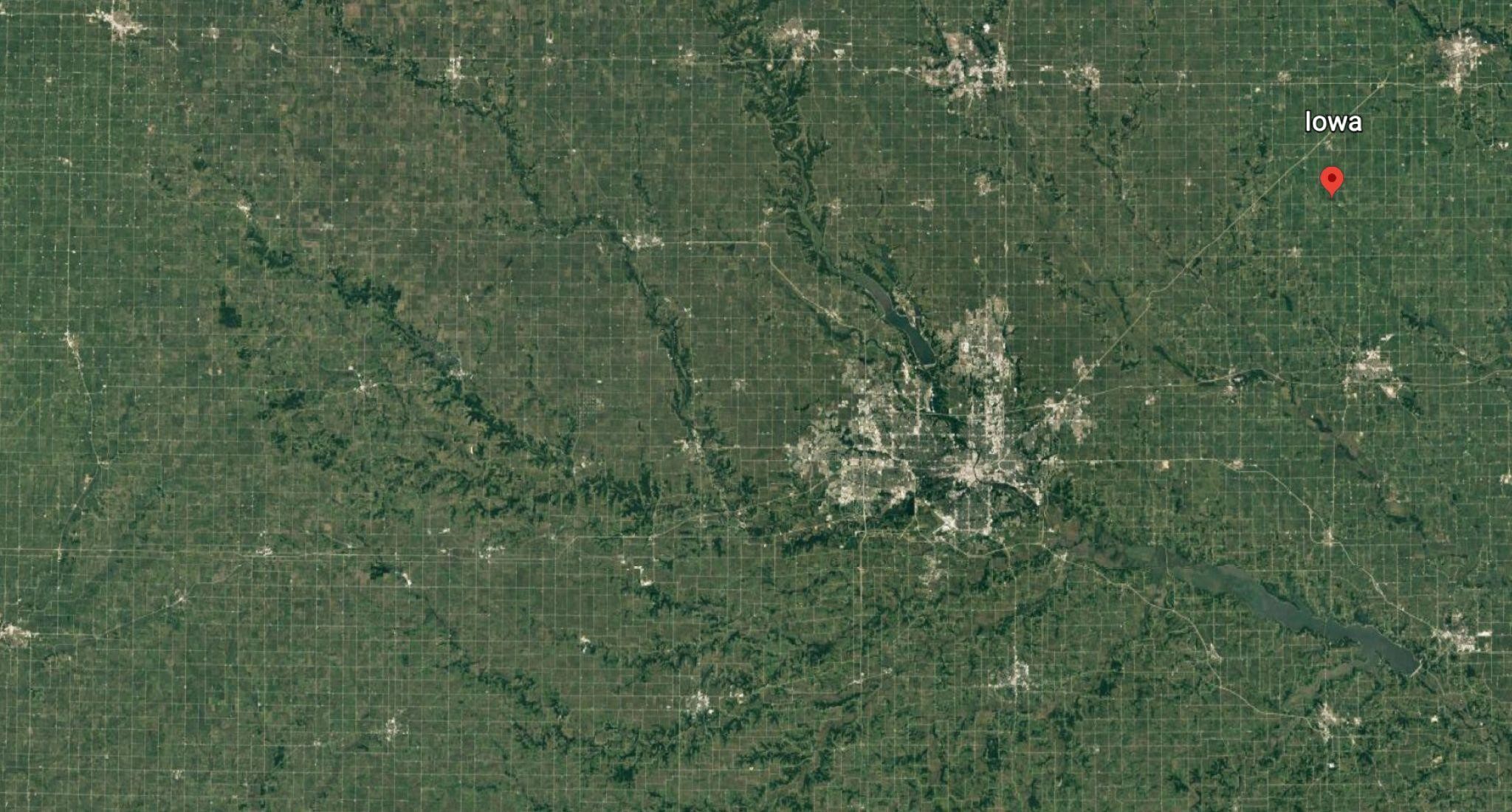

Exploring the effect and meaning of the 1784 Land Ordinance is far beyond the purpose of this paper and there is also ample literature documenting the subject. However the effects of this act are considered here as an adequate illustration of the idea of a gridded world, perhaps the most relevant being a banal satellite image selected by the author of this paper. The image displays the general shape of the American territory as an entanglement and interaction between the materialization of the Land Ordinance and other geographical forms (Figure 5).

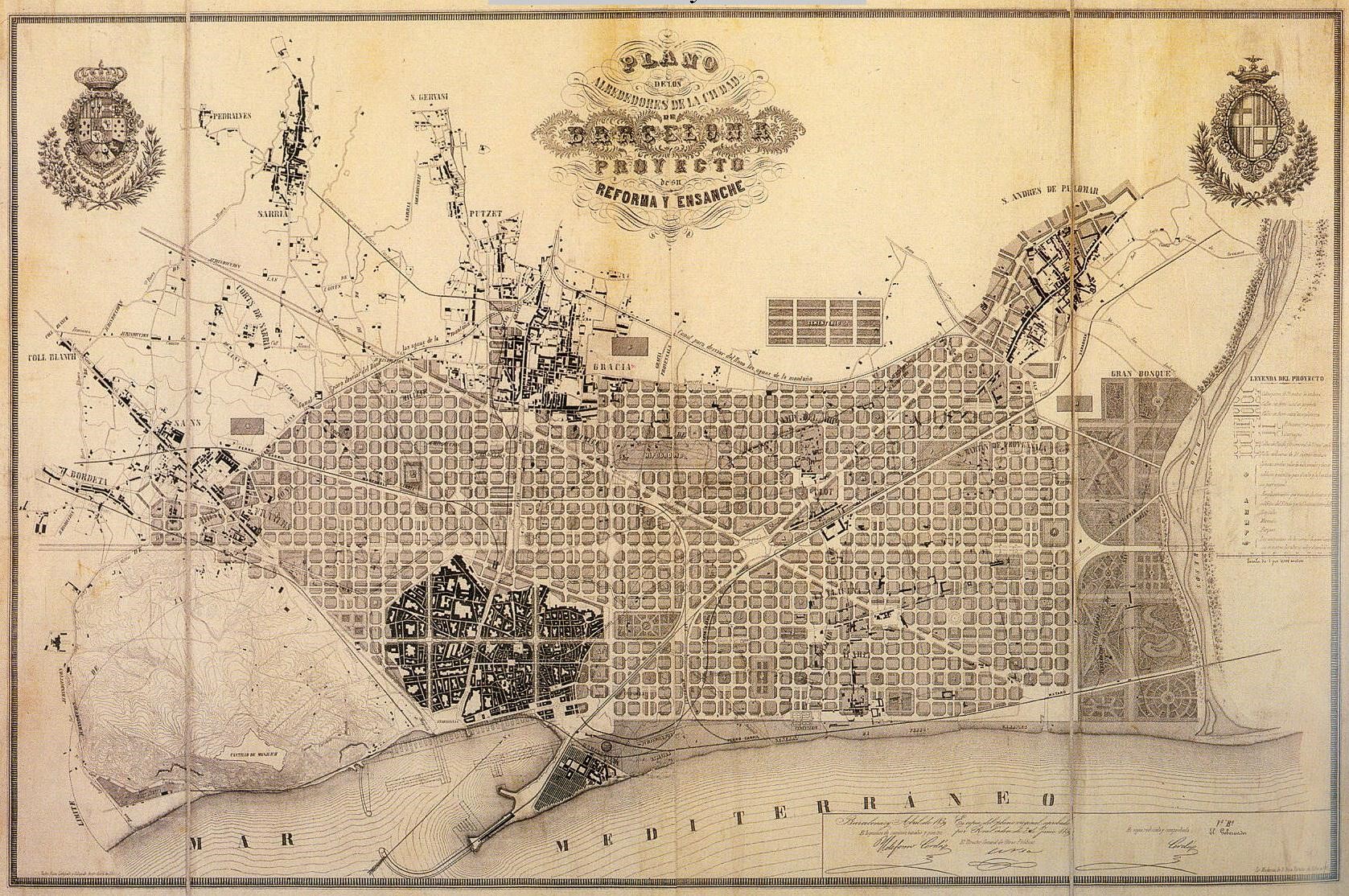

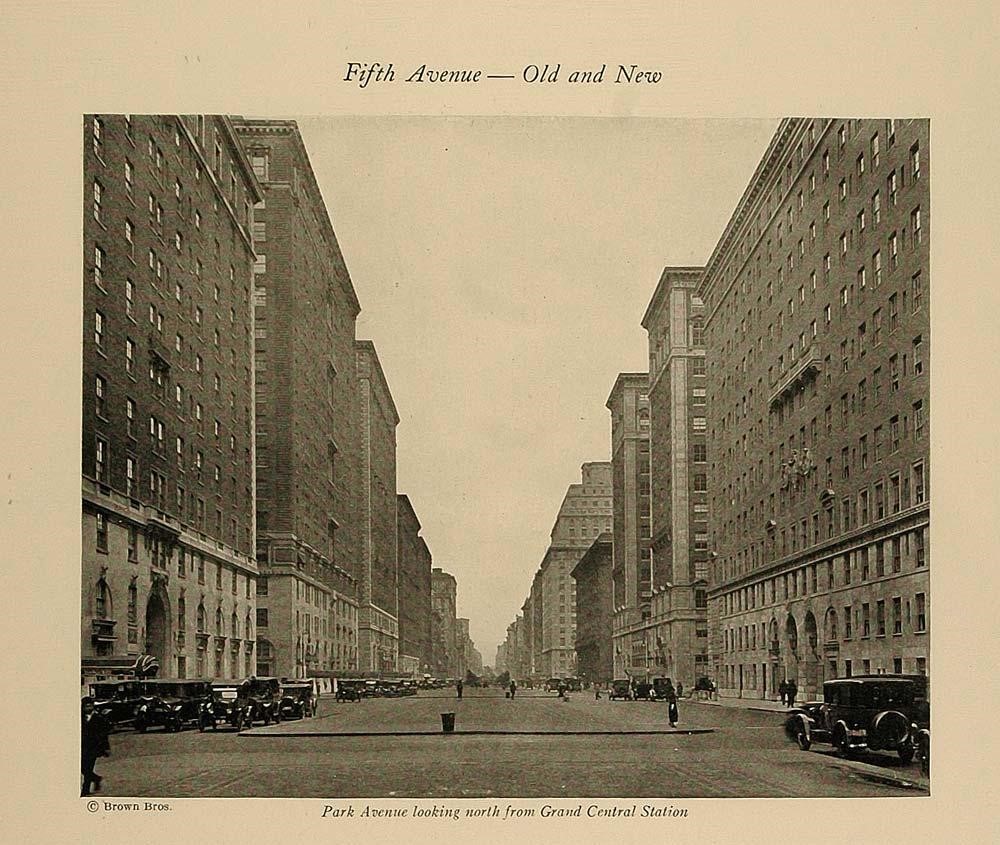

The highpoint of the orthogonal grid was probably the 19th century when the grid became the main tool for industrial urban expansion throughout the western world. Several well known city plans-turned reality can be showcased as examples: New York’s Commissioners Plan 1811 (Figure 9), Barcelona Plan Cerda (Ensanche Barcelona) 1859 (Figure 10).

At the beginning of the century, the world grid seems to be turning against the idea of the city through disurbanizing visions of society such as Frank Lloyd Wright’s BroadAcre city – a vision based directly on the Jeffersonian Grid.

During the 20th century the idea of a world grid started to show signs of crisis. The effects of this system would become central to the work of many artists and thinkers like landscape artists Robert Smithson, Nancy Holt, Michael Heizer who, under the imperative of the environmental crisis started to assess the qualities of the American Landscape and possibilities for a new synthesis between industry and nature. The grid thus became a basic tool for simultaneously assessing, interpreting and creating new ways of inhabiting the landscape.

The ethos of a gridded world

Teaching method: lectures, case study

Duration: 25 min

As previously mentioned the objective of the course is to equip students with basic conceptual tools for assessing existing grids in the Banat Region and encourage them to see grids as open ended cultural artifacts. The following section is concerned with the ethos of gridded visual space that emerged in the 15th century which is closely related to the development of actual urban space. A direct link between linear perspective and the spatiality of the urban environment is provided by Maria S. Giudici in her essay “Learning by numbers”. The author points to the importance of abaco schools in northern Italy, during the Middle Ages and how they determined the spread of linear perspective and the formulation of the urban project:

“Perspective finds in the abaco students its ideal vehicle, as they are trained in the geometric and mathematical exercises that form the basis for the construction of the perspectival image […]. It is the training of generation after generation of these foot-soldiers of accounting and surveying that allowed for the development of capitalism in central Italy and Europe at large […]. They were taught to see reality as a reified array of quantities and they transferred this understanding to the city, which gradually lost its symbolic and ritual meaning to become a field: for harvesting, for battles, for profit.[14]”

Combined with progress in cartography and overall cultural momentum we will propose the idea that starting with the 15th century a conceptual layer emerged that eventually enveloped the world and whose conflicting characteristics can be associated with the underlying order of the modern urban environment – we will occasionally name this layer the gridded world. Two authors have been selected for their writings on the subject: Canadian writer and founder of media studies Marshall Mcluhan, and German art critic Erwin Panofsky.

According to Marshall Mcluhan, The Renaissance was the moment when society plunged into a cultural environment based on the proliferation of technologies related to vision and our sense of seeing – a visual age. The most influential of these technologies was the Gutenberg printing press (cca. 1450) which, according to Mcluhan, generated the spatial and mental framework for the creation of most cultural artifacts of the age. Conceptually, the printing press brought about a matrix that was a grid and the possibility of an ever changing content through its movable types, a clear distinction between structure and infrastructure, a first model of serial production, and most importantly the spread of individual books throughout Europe.[15] In doing so it created an environment based on our sense of seeing, an almost purely visual space that inherited the main attributes of the printing press: repetition, visual control, homogeneity, one thing at a time, hierarchy. The more or less metaphorical grid of the printed press penetrated all bodies and, through abstraction, directly threatened the material order of things. In his book, The Gutenberg Galaxy (subtitle: The Making Of the Typographic Man) Macluhan attempts to explain numerous cultural events or artifacts as “translations” of the gridded environment.[16]

Apart from analyzing the impact of the printing press, Mcluhan was also preoccupied with how one could explore environments or phenomena from the midst of their unfolding, when it is difficult to achieve a critical distance.

In The Global Village and City as Classroom the author further describes the need for specific tools for probing the (urban) environment like the “Tetrad” or the creation of anti-environments through artistic practices that serve to “train perception”[17]. While the second concept is more theoretical and broad, the first has both a clear definition and is simple to apply: any technology will automatically enhance an aspect of society, while obsolescing another, it will retrieve a previous technology/quality and when pushed to the limits it will flip/turn into something else. Two examples of tetrads have been extracted from The Global Village:

“Perspective

Enhances private point of view

Obsolesces panoramic scanning

Retrieves specialization

Reverts into cubism/multiview”[18]

“Automobile

Enhances privacy: people go into their cars to be alone

Obsolesces the horse and buggy, the wagon

Retrieves a sense of quest – knight in shining armor

When pushed to the limits the car reverses the city into suburb and brings back walking as an art form”[19]

Also relevant for understanding the appearance of an all encompassing visual environment is Erwin Panofsky’s Perspective As Symbolic Form. The essay deals with the invention of linear perspective in the Renaissance. Panofsky also tracks down the formation of a homogenous, enclosed space permeating every aspect of the material world, and by the end of the essey one is left with the impression that once established, the perspectival grid became an abstract depository in which all of the world has symbolically poured in (and is now attempting to escape).

The author starts from the very simple premise (followed by a brief demonstration) that perspective for a long time was consciously used, not for accurately depicting the surrounding reality but for creating an autonomous space governed by idealized rules, where everything is geometrically bound. The author distinguishes between perspectival representation of antiquity where representation was bound to the idea of a finite, “real” space and that of Renaissance where a new, boundless space was invented – one that is disconnected from direct experience – a symbolic space.

The essay also looks at the diffrence between the perspectival grid and what laid before – medieval painting. In the latter space is the emptiness residing between the solid bodies in the painting, a kind of excavation of a solid mass. In linear perspective space permeates all the bodies on the painted surface, and everything that appears emerges from the condition of perspective and in relation to its rigid but clear lines – quantum continuum[20] (img. 1,2). An example of the quantum continuum described by Panofsky are the three plates: Ideal City (Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Figure 11), Ideal City (Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, Urbino) and Architectural Vedute (Gemäldegalerie, Berlin). The paintings display an empty architectural space, governed by the underlying order of a perspectival grid. Since there are no people one is led to believe that the paintings describe a decorum of a play that is about to start or perhaps an entirely new environment where people (colonists) are soon to arrive. The space appears infinite either by extending into the distance or by coming out of the picture to engulf the viewer. Each painting has a clear center – the vanishing point but it also expresses clearly the existence of a viewer by projecting outwards a vantage point.

What Panofsky sets out to demonstrate is the contradictory nature of perspective. The first three chapters of the essey track down the efforts of artists to develop a correct perspectival representation from a mathematical point of view, thus implicitly idealized and disconnected from individual experience – an objectification of the individual gaze. But as Panofsky points out, a number of meaningful contradictions emerge in relation to this apparent infinite and objective space:

Perspective in transforming the ousia (reality) into phainomenon (appearance) seems to reduce the divine into a mere subject matter for human consciousness. But for that very reason it expends human consciousness into a vessel for the divine. It is thus no accident if this perspectival view of space has already succeeded twice in the history of the evolution of art: first as a sign on an ending, when antique theocracy crumbled; the second time, as a sign of a beginning when modern “anthropocracy” reared itself”.[21]

The depiction of a struggle between a world dedicated to measurement, quantity or profit and a system that facilitates both personal expression and communal action is also a valid key for reading the emergence of the gridded urban environment and the way socio-political struggles played out in this new field.

Conclusion – being on and off the grid

The point of the first pair of authors is to attribute their concepts of structured visual space to the idea of an urban grid. Both authors spoke of visual environments established around the year 1500 that have characterized spatial organization ever since. E. Panofsky’s essay is relevant because it describes a conceptual tabula rasa or a space defined by mathematical relations – the perspectival cube, while Mcluhan defines visual space as an environment created by the printing press and the widespread distribution of printed materials.

Both authors describe gridded space as a radical change from a preceding reality – for Panofsky it is medieval painting where there was a clear demarcation between solid bodies and emptiness as opposed to Renaissance paintings where the new gridded reality seems to permeate both emptiness and fullness, thus canceling both. Marshall Mcluhan defines acoustic space as both preceding and succeeding visual space. If the latter is a byproduct of the mechanical age and mechanical technologies, acoustic space is a prerogative of electricity and the type of communication environment that electricity created. As opposed to visual space dominated by repetition, acoustic space is reflected in the concept of the Global Village, a non-linear, non-hierarchical spatial experience of a small world determined by instantaneous communication.

The idea that gridded space has a preceding reality is useful in setting boundaries to the concept itself.

A concluding distinction between the two can be extracted from Leonardo Benevolo’s work – the difference between “the art of occupying and inhabiting an infinite landscape” vs “the art of manipulating short and medium distances.”[22]

If the idea of manipulating distances can be attributed to perspective and to Mcluhan’s environment based on visual control and repetition, than also Benevolo’s art of occupying the unlimited landscape can perhaps be associated with the other two non-grid environments: Panofsky’s excavated space and Mcluhan’s acoustic space. In that sense if we were to consider our initial categorization of on and off grid conditions we will arrive at the following set of attributes for each of the two:

On grid:

quantum continuum penetrating all bodies, engenders visual control, repetition, homogeneity, connectivity and linear causality (one-thing-at-a-time), the art of manipulating distances, providing an objective framework for subjective expression, with artistic production

serving as a means of “training perception”.

Off grid:

excavated and limited, differentiation between empty and full (consideration to material qualities), discret, non-linear, simultaneous and boundless but not infinite with artistic production serving as a means of merging society with nature.

As the first condition is based on an emerging environment that encompasses nature and has produced such concepts as the “world coordinates system” or the Jeffersonian grid where the environment seems to be contained (Bucky Fullers’s Spaceship Earth) and the second is perhaps everything that is left out or that opposes the all encompassing view we can proceed to asking how can the two be combined: how could we move on from this distinction? We have looked at how the two categories interact historically but could we also look at these two categories as always present and always interacting?

The grid and the urban environment

Following a first definition of gridded space we will move on to discuss grids as urban shapes or tools for manipulating space within early and late modernity. Essential readings are the books “All That Is Solid Melts Into The Air” by Marshall Berman and “Ladders” by Albert Pope especially due to their idea that early modern grids are ripe for reexamination.

In his book All That Is Solid Melts Into the Air, Marshall Berman pleads for a re-examination of the basic premises of modernity as a way to understand how we, in the present, could come to terms with modernity’s maelstrom and what is to be done at this particular point within the urban environment. Berman wrote his book as a reaction to the apparent end of Modernity and transition to Post Modernity, which Berman sees simply as a continuation of modernity’s basic premises under circumstances of financial scarcity and socio-economic breakdown of the initial Modern Project.

Berman looks at the way Modernity has been expressed in some emblematic urban environments of the 19th century – Paris, Sankt Petersburg and New York. In the first chapter of the book the author describes the basic motor of modernity – the split between the need for development and overwhelming change (and loss) it creates. Ghoete’s Faust is used as a first conceptual illustration of this tension. According to Berman in the last part of the book Faust turns into a developer and starts a major project for land transformation involving the construction of a port and a lighthouse which require the destruction of a small house inhabited by people he once held dear. After introducing the basic plot of Modernity through the writings of Marx (C. II All That Is Solid Melts Into the Air: Marx, Modernism and Modernisation), Berman continues his examination with an analysis of Paris, Sankt Petersburg and New York. Similar to Panofsky, Berman looks at modernity through the lens of opposing qualities of the urban environment. A first example is Berman’s account of the nature of a typical Hausmannian boulevard, through the lens of Baudelaire’s poetry[23] where a poor family displaced by the reconstruction of Paris is strolling down a beautiful avenue. Reflective of the modern ethos in Berman view is a situation where the creation of large, straight boulevards was both the reason for displacing the Paris poor but also the stage on which they could become visible in the larger political context of XIXth century Paris and start fighting for their rights. The analysis of the modern urban environment as both stage but also active subject in different social and political events of the city is continued with the social life of Nevsky Prospect in Sankt Petersburg and finally with the author’s own account of the demise of the Bronx caused by the construction of the Bronx Highway by Robert Moses.

In the final two chapters of the book, “The 1960s: A Shout in the Street” and “The 1970s: Bringing It All Back Home” the author presents his own vision on how we could come to feel at home in modernity’s maelstrom and on the role contemporary art played the transition from high modernity to a more adaptive modernity that had to contract, slow down and develop creative ways of working with the past[24].

“Many modernisms of the past have found themselves by forgetting; the modernists of the 1970s were forced to find themselves by remembering. Earlier modernists have wiped away the past in order to reach a new departure; the new departures of the 1970s lay in attempts to recover past modes of life that were buried but not dead [when] modernism was under intense pressure to discover new sources of life through imaginative encounters with the past.”

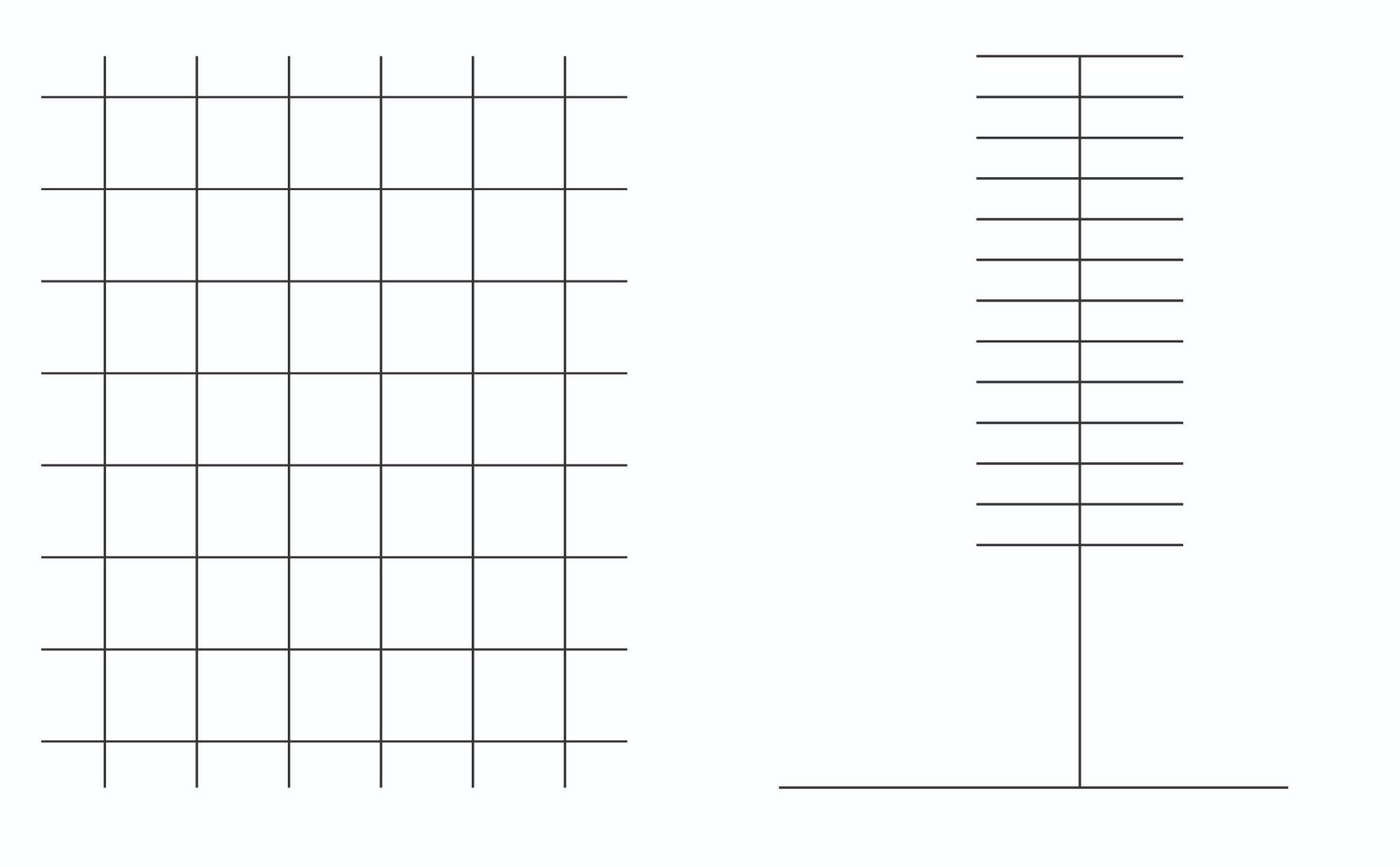

An actual analysis of the form and spatial devices of the modern settlement can be found in Albert Pope’s only book – Ladders. The author looks at the development of two very simple, very different and immensely impactful urban diagrams: the orthogonal grid and the ladder (Figure 12).

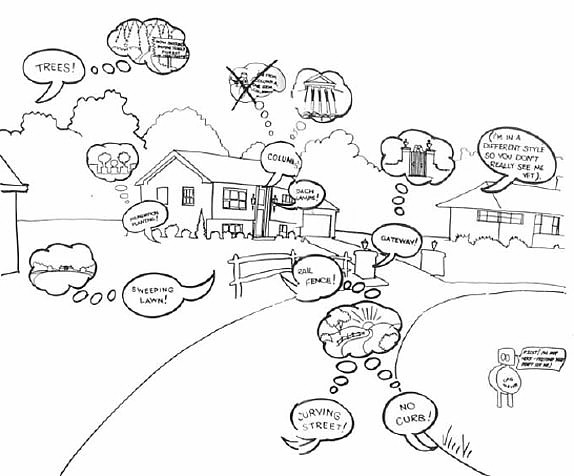

The book starts from the realm of visual arts analysis by quoting Rosalind E. Krauss’ “Grids”. Pope assigns Krauss’ distinction between a centrifugal grid that expands outwards and a centripetal one that collapses inwards to the evolution of the urban field, from early modernity to the contemporary city[25]. While the early modern city tended to expand and engulf the world (Figure 13) the late modern city is busy creating ever smaller enclaves that host increasingly controllable domestic universes (Figure 14).

In the first two chapters of the book (The Open City, Urban Implosion) Pope traces down the shift from centrifugal to centripetal urbanism in the years following World War 2 when the first signs of closure in the urban field occurred in Brooklin, New York. The author explains the phenomenon first of all through a need for segregation and control that emerged in relation to the apparent boundlessness of the orthogonal gridiron to then explain the origins of the ladder by analyzing the urban models created by Ludwig Hilberseimer, especially his planned erasure of Chicago and complete replacement with a ladder based structure.

Following the history of the emergence of the ladder, Pope describes the impact that this urban shape had on the overall urban field and what emerged from the conflict between old and new grids. He introduces several helpful concepts amongst which it is worth mentioning the “urban ellipsis”, a non urban area growing in the middle of the city, an urban void within the urban core.

In the last chapter of the book (Mass Absence) Pope raises the question of why the contemporary urban environment seems to be merely happening to us instead of being actively built by us – its inhabitants, and what role could architecture play in the development of the contemporary city. For Pope, the act of building the city must be based on the existence of a constituency that has been impossible to define in recent times.

When urban designers propose the revival of “public space,” for whom do they speak? What constituency has been located? What political, social, and cultural field is being brought into play, and who will be its players? Beyond any essentialist notions of urban community (for example, Clarence Perry’s “neighborhood unit”), in whose greater interests are such associations made? And exactly how and on what occasion may the politics of streets and squares be refused?[26]

Both Marshall Mclulhan and Albert Pope raise the question of what is to be done now and provide a somewhat similar selection of strategies realized by other artists, architects etc. Both authors refer to Robert Smithson’s work, the landscape artist that looked at art as a field of practice that can help mediate between ecological and corporate interests[27]. Thus landscape art is proposed as a field of practice that is capable of managing the unexpected outcome of the implementation of the world grid – a ubiquitous urban shape that no longer has a clear edge or contour and that is evolving increasingly complex intertwining with nature.

The project for the Banat region is anchored in the global realities and theories that have been analyzed up to this point. By being an act of internal European colonization, by the use of orthogonal grids and by the complex and nuanced relation between settlements, productive landscape and naturalized areas of land it is possible to also look at Banat through the lenses of financial exploitation vs personal engagement and public interest, controlled vs natural landscape or open vs closed grids or systems as a way to learn from what could be understood as a local laboratory of grids.[28]

[1] The following are a summary of the presentation delivered during the first Intensive Learning Programme, within the Triplex Confinium project. I would also like to underline that at this point the text is nothing more than a sketch for a larger research and is relevant mostly through the books it advertises. [2] O1. M1.02 The power of the grid: subordination and regularization in colonial territorial planning; O1. M1.03 Transformation and growth within the strict confines of the grid: economy, infrastructure and society [3] The origin and meaning of griddied settlements is still under debate. For more information on the emergence of this urban shape the following authors can be explored: Higgins, Hannah B. (2009) The Grid Book 2009, The MIT Press, USA - a history of grids characteristic to the brick, the tablet, city plan, the map, musical notation, the ledger, the screen, moveable type, the manufactured box, and the net. Redwood, Reuben-Rose and Bion, Liora (ed.) Gridded Worlds: An Urban Anthology , Springer International Publishing, 2018, eBook for an analysis of the origin of the gridded settlement and its evolution up to the Renaissance Benevolo, Leonardo (1975) The History of the City ed. 1988, MIT Press, USA - for a basic account of the origins and ancient history of grids and numerous illustrations and detailed plans for buildings and cities in the Neolithic Age and Classical Antiquity. Aureli, Pier Vittorio. “Appropriation, Subdivision, Abstraction: A Political History Of the Urban Grid.” Log, no. 44 (2018): 139–67. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26588516. - for an account of the connection between grids and their role as tools for appropriation of land and territorial expansion [4] Soja, James (2000) Postmetropolis, Blackwell Publishing, USA, p. 37 Learning from Catal Huyuk [5] [6] Benevolo, Leonardo (1975) The History of the City ed. 1988, MIT Press, USA, p. 108 [7] Aurelli, Pier Vittorio The Grid and the Island (2017) in New Investigations in Urban Form, Harvard GSD, video, min. 43-64 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0L7Anlsu2A4&t=3384s&ab_channel=HarvardGSD [22.07.2022] [8] Benevolo, Leonardo (1975) The History of the City ed. 1988, MIT Press, USA, p. 109 [9] Benevolo, Leonardo (1993) The European City , ed. 1993, Blackwell Publishers, USA, p. 4 [10] Benevolo, Leonardo (1993) The European City , ed. 1993, Blackwell Publishers, USA, p. 67-74 [11] Giudici, Maria S. Learning By Numbers, e-flux conversations , 2017 https://conversations.e-flux.com/t/superhumanity-conversations-maria-s-giudici-responds-to-zeynep-celik-alexander-mass-gestaltung/5784 [12.07.2022] [12] Klingaman David, Vedder Richard (ed.) Essays On the Economy of the Old NorthWest, Hughes, Jonathan, The Great Land Ordinances, 2011, Ohio University Press, Athens http://www.minnesotalegalhistoryproject.org/assets/hughes.pdf [12.07.2022] [13] Griffin, Sean Dwyer Lewis Masquerier And The Urban Origins Of An 1845 Plan For “Rural Republican Townships”, The Gotham Center For New York City History, 2015 https://www.gothamcenter.org/blog/lewis-masquerier-and-the-urban-origins-of-an-1845-plan-for-rural-republican-townships [12.07.2022] [14] Giudici, Maria S. Learning By Numbers, e-flux conversations , 2017 https://conversations.e-flux.com/t/superhumanity-conversations-maria-s-giudici-responds-to-zeynep-celik-alexander-mass-gestaltung/5784 [12.07.2022] [15] Before the printing press came about books were rare objects with significant material value. A clear image of men’s relation to manuscripts before the printing press can be experienced in places such as the Biblioteca Laurenziana, in Florence - the biggest public library at its time. Ancient manuscripts were chained to the benche, rarely being moved. If one wanted to switch from one topic to another one would move to another bench, not the other way around, as it is the case today when books are brought to the reader. [16] Mcluhan, Marshall, 1962, The Gutenberg Galaxy, University of Toronto Press, Toronto, p. 18 [17] Mcluhan, Marshall The Relation Of Environment to Anti-environment in Mcluhan, Marshall Mcluhan, Eric (ed.) Media And Formal Cause, 2011, Neopoiesis Press, Houston, USA p. 13 [18] Mcluhan, MArshall, 1989, The Global Village, Oxford University Press, New York, p. 169 [19] Idem p. 175 [20] Panofsky, E 1924, Perspective As Symbolic From, ed. 2012, Zone Books, USA, pp 30-31 “Exact perspectival construction is a systematic abstraction of this psychophysiological space. For it is not only the effect of perspective but also its intended purpose to realize in the representation of space precisely that homogeneity and boundlessness foreign to the direct experience of that space [...] it negates the differences between bodies and intervening space (empty space) so that the sum of all the parts of space and all its contents are absorbed into a single quantum continuum.” [21] Idem p. 67-72 [22] Benevolo, L 1993, The European City, ed. 1995, Blackwell Publishers, UK, p 3 [23] The author analyzes C. Baudelaire's In the Eyes Of the Poor, from his vol Paris Spleen [24] Berman, M 1982, All That Is Solid Melts Into Air, The Experience of Modernity, ed. 1988, Penguin Books, USA p 332 [25] Pope, Albert 2014, Ladders, Rice University Press, New York, p. 22 [26] Pope, Albert (1994) Ladders ed. 2013, Rice University Press, New York p. [27] Smithson, R (1970), Unattributed proposals in Berman, M (1982), All That Is Solid Melts Into Air, The Experience of Modernity, ed. 1988, Penguin Books, USA, p. 341 [28] The concepts proposed could be reflected in an urban analysis workshop - a plug-in into the exercises proposed by Mihai Danciu and Ștefana Bădescu în O1. M1.02 The power of the grid: subordination and regularization in colonial territorial planning.

References

Books

- Baudelaire, Charles (1947) Paris Spleen, ed. 1970, New Directions Publications, New York

- Berman, Marshall (1982) All That Is Solid Melts Into the Air Subtitle: The Experience Of Modernity, ed. 1988, Penguin Books, America

- Mcluhan, Marshall

- (1962) The Gutenberg Galaxy, The Making Of the Typographic Man ed. 1962, University of Toronto Press, Canada

- (1964) Understanding Media, The Extensions Of Men, ed. 2001, Routledge Classics, USA

- (1989) The Global Village, ed. 1989, Oxford University Press, USA

- (2011) Houston Texas, ed. 2011, Neo Poiesis Press, USA – published posthumously

- Panofsky, Erwin (1925) Perspective As Symbolic Form, ed. 1997, Zone Books USA

- Pope, Albert (1994) Ladders ed. 2014, Princeton Architectural Press, USA

- Higgins, Hannah B. (2009) The Grid Book 2009, The MIT Press, USA

- Redwood, Reuben-Rose and Bion, Liora (ed.) Gridded Worlds: An Urban Anthology , Springer International Publishing, 2018, eBook

Articles

- Stanislawsky, Dan The Origins and Spread of the Grid Pattern Town p. 21, in Redwood, Reuben-Rose and Bion, Liora (ed.) Gridded Worlds: An Urban Anthology , Springer International Publishing, 2018, eBook

- Redwood, Reuben-Rose Genealogies of the Grid: Revisiting Stanislawski’s Search for the Origin of the Grid-Pattern Town p. 37, in Redwood, Reuben-Rose and Bion, Liora (ed.) Gridded Worlds: An Urban Anthology , Springer International Publishing, 2018, eBook

- Aureli, Pier Vittorio. “Appropriation, Subdivision, Abstraction: A Political History Of the Urban Grid.” Log, no. 44 (2018): 139–67. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26588516.

Illustrations

Figure 1 – Wall painting from Catal Huyuk – possible depiction of the city

Source: https://www.historyofinformation.com/detail.php?id=1437

Figure 2 – First maps of the city of Caracas 1578 (left)

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:First_Map_of_Caracas,_1578.jpg [19.07.2022]

Figure 3 – Scientifically gridded globe

Source: Masquerier, Lewis (1847) A Scientific Division and Nomenclature of the Earth, 1847, p. 4

Figure 4 – The National Reform township Plan (1845), from Principles and Objects of the National Reform Association, or Agrarian League, New York,

Figure 5 Satellite image, Iowa, USA Source: Google Earth, viewed 12.10.2021

Figure 6 Corner, J, McLean, A 1996, Taking Measures Across The American Landscape, ed. 1996, Yale University Press, New Haven&London, p 50

Figure 7 – Corner, J, McLean, A (1996), Taking Mesures Across The American Landscape, ed. 1996, Yale University Press, New Haven&London, p 48

Figure 8 – Corner, J, McLean, A (1996) Taking Mesures Across The American Landscape, ed. 1996 Yale University Press, New Haven&London, p. 76

Figure 9 – Coneybeare, Matt (2019) Manhattan From Above in 1931

source: https://viewing.nyc/this-incredible-vintage-aerial-photograph-shows-manhattan-from-above-in-1931/ [12.10.2021]

Figure 10 – Plan Cerda, Barcelona (1859),

Source: https://historyofbarcelona.weebly.com/plan-cerda.html [7.19.2022]

Figure 11 – Fra Carnevale, 1480-84, Ideal City, Wikipedia https://ro.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fi%C8%99ier:Fra_Carnevale_-_The_Ideal_City_-_Walters_37677.jpg [12.10.2021]

Figure 12 – Diagram of grid (left), diagram of ladder (right)

Source: the author

Figure 13 – The centrifugal city

Figure 14 Venturi&Scott Brown and Rauch, Cartoon Representation of Suburban Architecture (the centripetal city)

Source: https://www.quondam.com/40/4016j.htm [19.07.2022]

Grid Closure

3. Holme, T 1683, Green Country Town (Philadelphia), image, Wikipedia Commons, viewed 12.10.2021

4. Nevius, J 2017, Inside the Architect’s Overlooked Plan For Broadacre City, Curbed, viewd 12.10.2021 [https://archive.curbed.com/2017/1/4/14154644/frank-lloyd-wright-broadacre-city-history]

The image displays Franks Lloyd Wright’s vision for a disurbanized America and a new type of occuping the land based on infrastructure and lofty space for every inhabitant. The project was named Broadacre City by the author in reference to the idea that each inhabitant would have one square acre of land at its disposal.

5. Construction of the Cross Bronx Express Highway 1959, image, Twitter, viewed 12.10.2021 [https://twitter.com/discovering_nyc/status/611916117620076545]

6. LBJ Freeway under construction in 1965, image, Pintrest, viewed 12.10.2021 [https://ro.pinterest.com/pin/14073817558004352/]

Grid and the territory (follow up on the effects of the land ordinance and other orthogonal grids)

9. Corner, J, McLean, A 1996, Taking Mesures Across The American Landscape, ed. 1996, Yale University Press, New Haven&London, p 45

11. Google Earth, 2019, image

The image displays an area equal to 1 sq mile of land, tracing the Land Ordinance of 1784.

12. Smithson, R 1971, Broken Circle/Spiral Hill, image, Eflux, viewed 12.10.2021 [https://www.e-flux.com/announcements/34320/robert-smithson-the-invention-of-landscape/]

References

Books:

Corner, J, McLean, A 1996, Taking Mesures Across The American Landscape, ed. 1996, Yale University Press, USA

Panofsky, E 1924, Perspective As Symbolic From, ed. 2012, Zone Books, USA

Panofsky, E 1951, Gothic Architecture And Scholasticism, ed. 1970, Meridian Books, USA

McLuhan, M 1962, The Guttenberg Galaxy, ed. 1962, Toronto University Press, Canada

Mcluhan, M, Powers, R P 1992, The Global Village, ed. 1992, Oxford University Press, USA

Pope, A 1994, Ladders, ed. 2014, Princeton Architectural Press, USA

Berman, M 1982, All That Is Solid Melts Into Air, The Experience of Modernity, ed. 1988, Penguin Books, USA

Benevolo, L 1993, The European City, ed. 1995, Blackwell Publishers, UK

Video:

Aureli, P V, 2018, Reconstructing the Agency Of Form, Part 1, video, Youtube, viewed 12.10.2021 [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0L7Anlsu2A4&t=3906s&ab_channel=HarvardGSD]

Other Instructors

Alexandru BELENYI

Researcher

Irina TULBURE

Assistant Professor

Irina BĂNCESCU

Assistant Professor

Ilinca PĂUN CONSTANTINESCU

Teaching Assistant

Cristian BORCAN

Teaching Assistant

Cristian BĂDESCU

Teaching Assistant

Syllabus

The underlying premise of the course is to stress out the importance of theory in architectural education as an area of experimentation and exercise where students learn how to see. This is particularly important when dealing with analysis of the urban environment. Albert Pope clearly formulated this imperative in the introduction to his book Ladders: “The contemporary city that is at this moment under construction, is invisible. Despite the fact that it is endlessly reproduced, debated in learned societies and suffered on a daily basis, the conceptual framework that would allow us to see the contemporary city is conspicuously lacking. While it remains everywhere, and always in view it is fully transparent to the urban conceptions under which we operate.” [1] 1. Pope, Albert Ladders, 1994, Ladders, ed. 2014, Princeton Architectural Press, USA p. 2

O1.M1 UNDERSTANDING THE TERRITORY AS A SYSTEM

O1.M1.01 Grids, Formal tools for understanding and manipulating space

Type of format

Lecture & Workshop

Duration

50 min lecture (theoretical notions & case studies) 10 min break 50 min lecture (theoretical notions & case studies) Workshop 8 hours (mapping and analyzing gridded settlements in the region of Banat)

Possible connections (with other schools / presented topics)

UAUIM O1. M1.05 Borders- theoretical research framework UAUIM & FAUT O1. M1.04 Reinventing the grid: the thin line between relevance and oblivion BME O1. M3.02 History drawn in the landscape- Border imprints and how to read them - Working with the cultural landscape

Main purpose & objectives

The main purpose of this class is to help students understand and recognize the complexity of an apparently simple and straightforward urban shape and its impact on today's world. The objectives of the course are: Introducing students to the notion of gridded settlement by providing a succinct history of the grid based cities and city plans. Providing a basic framework for understanding gridded space in visual arts by discussing the apparition of linear perspective and the notion of a visual environment triggered by the invention of the printed press. Selected reading Irwin Panofsky, Perspective as Symbolic Form Marshall Mcluhan, The Gutenberg Galaxy Understanding grids as basic tools of modernity by looking at authors that propose a reassessment of the primary ethos of modernity and discussing the evolution of urban grids starting at the beginning of the 19th century Selected reading Marshall Berman, All That Is Solid Melts Into The Air Albert Pope, Ladders Reconstructing the Banat construction kit - analyzing the settlements of Banat by comparing their basic structure and the way in which successive public programs have been developed and absorbed into the structure of settlements, overtime. Abstract exercise - Redrawing grids of Banat as diagrams of spatial organization The class therefore concentrates on the following cross sectional objectives: -introducing students to the basic notions around the concept of grids and up to date research on the topic -analyzing the theoretical principles in relation to their application, meaning and impact -understanding and recognizing the theoretical notions discussed using different case studies to illustrate each specific situation The learning methodology: extensive and diverse literature on the topic, case studies analysis, mapping, sensitive readings of research area, typology, index, comparative critical analysis etc.

Skills acquired

Apparatus for critical thinking & conceptual toolkit The course aims to further develop students’ apparatus for critical thinking by reviewing several books and theory papers that have developed critical perspectives on gridded spaces in visual arts and urban theory. By being briefly exposed to dialectical interpretations of key historical moments such as the apparition of linear perspective, the impact of the printing press, centrifugal and centripetal space or open and closed grids students will also acquire a set of conceptual tools they can further investigate on their own. Abstraction and analysis skills Students will engage with a rich visual material consisting of mostly abstract or conceptual representation of grids. This is expected to develop their abstraction and analysis skills and supply a basic toolkit for abstract representation and analysis that can be further developed by students. Visual representation skills By critically engaging with visual representation and analysis of grids in the Banat region, it is expected that students will be able to increase their ability to use the proposed instruments and methods, becoming more aware of their role as future architect-mediator and the impact of social, cultural, geopolitical factors on today’s built environment.

Contents and teaching methods

1. Introduction - Short history of the evolution of gridded settlements Teaching method: introductory lecture 2. The Ethos of a Gridded World and Gridded Visual Space Teaching method: lecture, case studies 3. The Grid and the Urban Environment Teaching method: lecture, case studies 4. Building a library of grids - case study on the Banat Region Teaching method: workshop, visual representation

Reviews

Lorem Ipsn gravida nibh vel velit auctor aliquet. Aenean sollicitudin, lorem quis bibendum auci elit consequat ipsutis sem nibh id elit. Duis sed odio sit amet nibh vulputate cursus a sit amet mauris. Morbi accumsan ipsum velit. Nam nec tellus a odio tincidunt auctor a ornare odio. Sed non mauris vitae erat consequat auctor eu in elit.

Members

Lorem Ipsn gravida nibh vel velit auctor aliquet. Aenean sollicitudin, lorem quis bibendum auci elit consequat ipsutis sem nibh id elit. Duis sed odio sit amet nibh vulputate cursus a sit amet mauris. Morbi accumsan ipsum velit. Nam nec tellus a odio tincidunt auctor a ornare odio. Sed non mauris vitae erat consequat auctor eu in elit.