Think Brick! is a competition addressing students and young professionals willing to reimagine Jimbolia’s former industrial area, through means, strategies and tactical approaches of all scales that can emphasize to local and regional communities the rich cultural, natural and built heritage developed around brick production and bricklaying techniques.

Preamble

Triplex Confinium is an ERASMUS+ strategic partnership between the architecture schools in, and around, the DKMT Euroregion. In all, it ecompases five architecture schools of different sizes, a geography faculty and a sociology department.

From its onset Triplex Confinium’s mission was to tackle the gaps and mismatches between partner countries educational programs within the field of architecture, while, at the same time, looking at the spatial discontinuities along the borders of Hungary, Serbia and Romania. But these discontinuities, gaps and mismatches include not only real observable territorial issues. They can be as easily traced along the lines of national accreditation systems within higher education, teaching methodologies, and thematic interests. Naturally, partners agreed to search for some common ground. This could be mapped physically, in the territory spanning between our schools (our common hinterland), as well as academically, through learning experiences leading towards a new joint curriculum. A hybrid program that mixes different educational modules with a competition, showcasing not only the schools themselves but the many missions future architects will be faced with when dealing with this hinterland.

The program is imagined as a flexible international curriculum with three main components:

- The Open Competition

- The Summer Schools

- The Debates

The Open Competition is an invitation to all students and young professionals in Romania, Hungary and Serbia to engage in a project driven debate about the future of the architecture education and profession in the hinterland.

The Summer Schools (September 2021 and April 2022) will provide students from the Triplex Confinium partner schools competencies related to critical thinking, site exploration and project implementation.

The Debates will bring together stakeholders relevant for both the analysis and improvement of the methods tested within the program, but also for the further dissemination of the project results.

We strongly believe that the competition, the learning modules and on site experiences, as well as the final proposed projects should allow students and tutors with different backgrounds and academic levels from all neighbouring countries to discover each other, as well as their professional condition within these hinterlands.To achieve our mission we have chosen to l1ook at this territory using a conceptual framework that captures the very essence of this region’s material and immaterial culture, its main building block: brick.

This document is focused on the first component of the program, The Open Competition.

One can follow our entire program on the Triplex Confinium website: www.triplex-confinium.eu

Brick

Brick is, arguably, the most architectural of all building materials. Brick is timeless. It defies geography, culture or tradition. Our written history coincides with its early uses not only as a building block but as a medium for storing information. Brick is born of the land, moulded with water, baked in the sun and fire, and thus transformed into an abstract building block, that defies any intellectual interpretation. Its semantic language is self referential. Brick dictates technique. Technology follows suit. Brick will do and be, as Louis Kahn noted, only what it wants to do and be. Perhaps herein lies its undying appeal, for it is a material that commands its way into timeless forms and spaces, a material that empowers light and metaphysics without the need of any decorative embellishment or intellectual alibi, a material that is both utterly functional just as much as it is poetic, ancient and modern at the same time, resilient and sustainable.

By choosing brick we are not only choosing a material that lies at the very core of the architectural discourse but also reinterpreting the rich brickmaking tradition once visible in this region. Jimbolia (Ro) and Kikinda (Srb) were until the end of the XXth century, power houses within this industry. Brick not only built this region’s villages and towns and cities, but its economy as well, and through it, its culture. A culture that, just as its economy, seems at a loss for present day communities. Think Brick would like to deal with this loss, and reopen a debate around our profession, and our mission as architects dealing with such complex issues. Think BRICK!

Source: Anton Schenk via Heimatblatt Hatzfevld 13, 2006; Heimatortsgemeinschaft Hatzfeld

Historical background

The history of the Banat region, from its XVIIth century Habsburg spatial, economic and cultural re-programming until today, can be seen as impressions left in the landscape. The initially marshy area was easily drained due to the advances brought about by the industrial revolution, with the farmland created through this process becoming the largest and best quality agricultural region in the Habsburg Empire, which, in turn, made the estate owners here extremely wealthy. Subsequently the income originating from agriculture was invested in brick factories to exploit the excellent quality clay to be found here, which, following the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, turned into a huge network in unison with the development of the region of Banat.

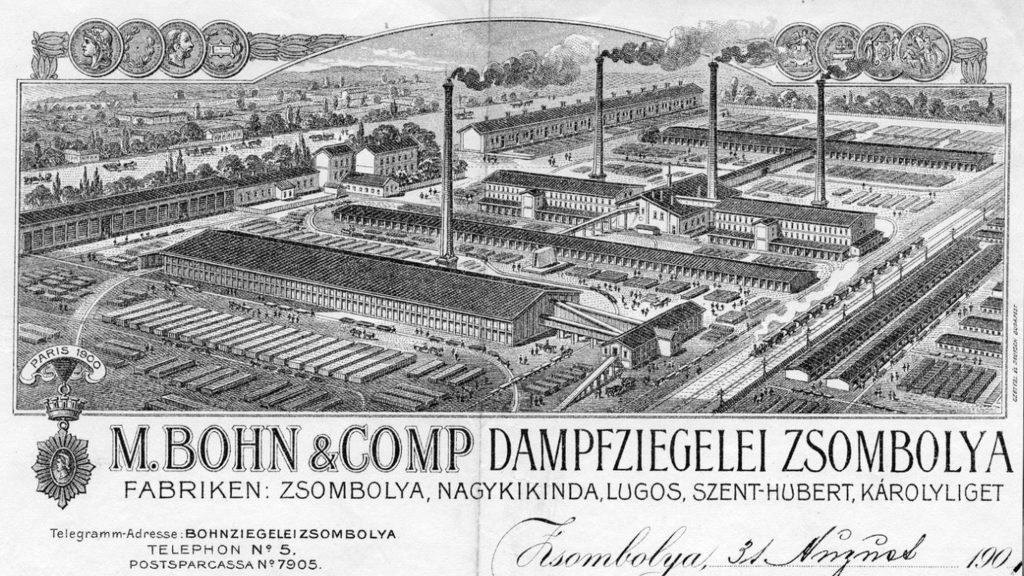

Through its many industrial facilities, (Bohn, Muschong, Treiss), Jimbolia (RO) has been, as early as the XIX century, at the forefront of brick and tile production within the region. Similar brick production facilities and clay pits were functioning throughout it. Clay products from Jimbolia or Kikinda were used throughout the entire Austro-Hungarian Empire, and were even presented and certified for their quality at the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris. The best example portraying this european dimension can be seen in the case of the local brick factory producing bricks for the reconstruction of Szeged following the Great Flood of 1879. Hence, the brick factory’s history and its heritage is not only an important part of the past of Jimbolia, but of the entire region. After the Great War the Treaty of Trianon split the region up into three parts, which put an end to this previously unified development.

Source: Walther Konschitzky; Die Ziegel-Rivalen Bohn und Muschong; Heimatblatt Hatzfeld 18, 2011; Heimatortsgemeinschaft Hatzfeld

Brick production, however, has remained a staple of the local economy alongside agriculture and other smaller manufacturing enterprises, even during the communist administration. Yet it is communism that set the path toward oblivion, through the systematic destruction of Jimbolia’s entrepreneurial class and their family owned businesses. Even as late as the interwar period, Jimbolia’s functional, economic and cultural raison d’etre remained relevant mainly through its entrepreneurial class and its many transnational networks. In many respects this multiethnic class supported not only it’s economy but it’s cultural assets as well, social clubs and community programs, setting the tone of its development and social progress. One can rightfully argue that Jimbolia’s gradual transformation into a cul de sac can be traced back to this initial loss of it’s societal and economic structure.

Jimbolia’s current efforts in showcasing this rich social and cultural history are visible today in its six different museums and memorial houses. Right on the outskirts of the competition site, the Railroad Museum is home to several early XXth century rail equipment, cranes and, until recently, a steam engine. The old water tower is still standing next to the brick clad historic train station. The “Florian” Fireman’s Museum, managed by the local volunteer fireman’s brigade, is home not only to several historic fire fighting vehicles but to all sorts of paraphernalia and memorabilia. Not far away, the Stefan Jager Museum captures the life and work of the most famous painter of the Banat Swabians.The “Sever Bocu” press museum is home to an extensive collection of unique newspapers from around Romania, dating back to the middle of the XIX century. The collection donated by the famous writer and journalist Petre Stoica, has gained great attention from researchers and historians. One last memorial house is dedicated to the famous doctor Karl Diel, a prominent figure in the cultural and social life of historic Hatzfeld at the turn of the XIXth century.

Unfortunately, none of these cultural facilities capture the rich history of industrial brick production and its role in developing the local community. Foreign eyes are as oblivious to this history as are those of young Jimbolians.

Source: Josef Koch

Problem definition

The 90s decade, with their often corrupt and purely speculative transition processes, dealt a final blow to these once proud regional enterprises. In the case of Jimbolia the factories were dismantled brick by brick, only the clay quarries remaining as a new natural feature of cultural and environmental importance. As an anthropic landscape shaped by man through industry, yet gradually reclaimed by nature during the past two decades, the quarries remain a silent witness to a bygone era. One walks around their trails without even imagining the many industrial apparatus, rail lines and laborers permanently toiling in its depth. It is not only regional history that was lost under their waters but real personal stories as well. With many informal functions overlapping: natural habitat, illegal garbage dumpsite (in the northern part), recreational areas filled with obsolete playgrounds and parasitic structures, their status is currently uncertain even to the local community. And how else can it be, when even similarly important traces are barely visible in this geography of loss.

At the same time, the recent decades of European integration, following the transition into democracy, have once again created the opportunity for tighter relations between the parts of the formerly unified region. What are the common features, opportunities and ambitions of the former Banat? Can this site be reevaluated in a larger euroregional framework, one that is in tune with similar european endeavours while clearly remaining of the land and for its people.

Source: Josef Koch

Hypothesis

A problem this deep situated at the intersection between built heritage, nature, regional history and multiculturality, economic speculation and political decision is prone to various interpretations. Some statements have to be made to guide the design process and better determine the scope of the competition through a viable hypothesis.

Contenders are invited to formulate their own hypothesis on the problem at hand, while exploring the strategic site, decoding its history and untapping its potential future states. The former industrial area with its clay quarry, (now a natural park), the Futok workers colony and main railway station will serve as the strategic site offering participants with a background on the development of the area and its genius locci. The different interventions and working hypotheses imagined will however be organised in and around the quarries area. Around these, proposed projects are free to explore at all scales and through various building programs, ways in which the site can be recovered, all while strengthening its natural qualities.

Source: Bogdan Demeterescu

Competition site

Considering this hypothesis the competition brief argues that the quarry lakes can offer contenders with an ideal setting for exploration, and interpretation. The six lakes formed in the abandoned clay quarries are located in the northern part of the settlement, beside the largely deserted and unused area of the former brick factory. They create a natural border between the urban environment and agricultural land.

In their current natural state, the lakes are a good reference point for observing the interaction between human activity and the landscape, both past and present. Clay quarries were a common site around Jimbolia, and in fact all colonial settlements, as far back as the 18th century. For local building purposes, early colonial dwellers would dig clay pits (kaule) at the end of each street. It is only with the arrival of Stefan Bohn, an entrepreneur native of nearby Sankt Hubert that the first large quarries are opened in the northern part of the Town. Bohn took advantage of the new rail line built between Budapest and Timisoara in 1857. Seizing this opportunity Bohn scouts for clay to the north of the train station and his intuitions prove right. His business expands as do others in the area, and Jimbolia quickly develops a sizable industrial zone. The first quarries were dug manually by Kubikas, intensive laborers, paid by the cubic meter. They were living in makeshift barracks in the vicinity of the quarries. Later on, these laborers were invited to build the workers colony of Futok. In the early XXth century heavy machinery was introduced. The quarries were from now on exploited using huge excavators set on railroads (the remnants of such a machine can still be spotted in the deepest lake). The clay was transported in small trains along a complex system of rails that linked each quarry to the nearby factory. There, the clay was cleaned of impurities (shells, stones and even mammoth bones), mixed in various recipes, shaped in special molds, dried and later burned in huge ovens, some spanning more than 100 meters. The production values were enormous. Before The Great War, Bohn was producing 18 million tiles and 8 million bricks per year. His nearby competitor Threiss was producing just as much. The production figures were doubled by the second world war. Bricks were exported not only in Hungary or Austria but as far as Greece and the Middle East.

The lakes themselves were created naturally, as extraction progressed throughout the site. The accumulation of water has been an issue even during clay extraction and several measures were devised for the control of surplus water. The quarry pits were connected with underground pipes and flotation pumps that would flush the water from one another as needed. This topographical project was extremely important in order to fulfil the different recipes of brick that the factories produced. Several quarries were opened at the same time. These had different depths, some going as far down as 30m.

The factory continued extracting clay well into the 9th decade of the XXth century. It is the economic chaos of the 90’s that the Romanian state decided to abandon production, dismantling all built structures, selling it for scrap metal. The process was quick and the community, faced with financial difficulties, agreed to sell all of its assets.

The lakes are the only man made structure still visible of this great industrial project. In the two decades that followed they have been gradually reconquered by nature. Ironically, as industrialized agriculture has taken hold of the nearby fields these lakes have transformed into an oasis for natural wildlife. They are currently an informal place for recreation used mainly by the local community either for fishing or bird spotting. Swimming is officially prohibited as several deaths have occured in the past years. These were caused either by the algae growing in shallow waters or by the cold currents inhabiting the deeper pits. These have variable depths that quickly and unpredictably change the temperature of the water. While some lakes are truly deep some are drying out, as the water leveling system stopped working two decades ago. All connecting pipes are now above the water level. This creates an interesting landscape with different kinds of water textures. Birds flourish in this environment.

Local administrations have proposed various projects for regenerating the site, some going as far as proposing a water adventure park. The latest one imagines a place dedicated to bird watchers and nature enthusiasts. None, however, planned to reinterpret the industrial tradition, the memory of the production facilities and the many stories that it spanned.

Objectives

The main objective of the competition is to generate a generous debate about the possibilities of this site in particular, and about such sites, in general. The debate should be relevant for both local communities and professional ones, and the projects developed through this tool should either be very pragmatic and easy to implement, or with a very strong conceptual value thus instigating a more elaborated approach to the site or problem.

Three categories of projects can be submitted:

- small scale, tactical interventions that form various forms of networks connecting and telling the story of the site

- visible structures (pavilions, small buildings) that become part of the site’s image and are used to frame and present it

- landart/ landform interventions that work with the site’s topography and allow for a better understanding and parkour throughout the entire area

When working within these categories, one should have in mind the following objectives:

- The project needs to be well adjusted to the needs and capacity of the local community. (in creation, implementation and use)

- The project needs to use local materials and be conscious about the local environment.

- The project needs to address both the current character of the site and its historical and cultural legacy.

- The project needs to have a contemporary language and approach.

- The project needs to connect to the wider context of Jimbolia as both a particular place and a typological one.

Source: Francisc Jung