O1.M3.01 Recognition by small scale intervention

Free

About this course

Sessions:

- Site recognition through social inclusion, with community interventions

- Site recognition with site-specific installations in natural and urban environments

- Building recognition with site-specific installations

- Complex in-site workshop

There are now countless technical options for geometrically mapping a site, from traditional manual surveys to automated solutions, including 3D scanning. We can think that we have all the necessary information about the place, relevant knowledge to plan an architectural intervention. However, in addition to these strict geometric parameters, there is also a lot of objective or subjective information related to the place, which may have similar or even more important attributes. Deciphering this information, which is sometimes quite hidden, requires a very different, complex approach, is not really standardised, and is highly dependent on the specific site.

The relativity of the perception of space has inevitably given rise to a segment of the spatial installation that affects the map-sense. The expression of the tension between the perception (doxa) arising from the fallible senses and the knowledge (episteme) governed by reason became the subject of art, in our case, spatial installation. Reality and its mathematically describable space do not coincide with perceived space or with the image of perceived space.

The four suitable teaching modules aim to introduce an active way of knowing space, the knowledge of space through art, by presenting three different basic situations in detail and analysing case studies, and then, in the fourth, by exploring a real site using the methods learned.

1. Site recognition through social inclusion, through a co-created intervention

Chapter 1.0 General introduction to the topic

Teaching method: lecture

Duration: 30 min

The change in the economic environment has naturally transformed architectural thinking, its focus and, in many cases, its direction. The impact of this change can be felt in the field of architectural design, architectural theory, education, and the strengthening of the research approach. The architectural market has been transformed, the tasks associated with architecture have been redefined, and new areas have emerged in which the role of the architect has become more prominent. Architecture is no longer just a matter for architects, but has been superimposed on many other disciplines and specialisms, fertilising architectural thinking. In the same way, architecture has become an integral part, a driving force and, in some cases, the foundation of many other fields.

It is in this climate that a particular methodology of architectural design is developing: the possibility of applying community-engaged design at a systemic level. Experiments carried out in recent decades illustrate the potential of this approach. Methodologies have emerged from practical experience. Their use has been partly facilitated by the emergence of rationality in the economic environment and in thinking, as they are the only way to achieve profitable, rational architectural interventions.

The process of community-based design typically starts at the preparatory stage. Even before the architectural concept is developed, the first step is to identify local resources, real needs and hidden architectural conditions. Only if the programme is embedded locally can a profitable architectural programme be realised. This process requires a specific architectural presence, which is far from being architecture-free. Small-scale interventions, minimal construction can be a spectacular means of visibility, with the capacity to discover active communities, to reach out to local social strata, to future users. The act of addressing and then creating together is a bonding force and helps to deepen knowledge, and can be interpreted as a form of visual education and knowledge transfer.

Chapter 1.1. Introduction to the methodology of space awareness, general presentation of community actions and interventions

Teaching method: lecture

Duration: 30 min

Methods of spatial cognition in the field.

The collection of data on a site must be combined with an understanding of the physical characteristics of the site. This can be done through space and environment discovery games carried out by the architects (students). The method of knowing the space is not limited to the analysis of the collected local history and maps, the focus is on the knowledge of the physical characteristics of the place. These experiences facilitate the discovery of the local socio-economic conditions that can have a binding impact on the design process, from the formulation of the architectural programme.

The spatial cognition games explore the properties of space (place) such as scale, spatial proportions, characteristic materials, identities and differences of the architectural environment, properties of spatial perception (light, sound, smells), spatial phenomena linked to movement (transport, movement in space), the knowledge of stories based on local knowledge and experiences (local history layer). These are all components that can only be born from the field, from the ‘in situ’ knowledge of the design site. In addition, guided creative games contribute to the mapping of the local context, starting the process of getting to know the local people, of embedding. The aim is to achieve the possibility of “becoming local”, through which awareness-raising is also achieved, leading to the acceptance of subsequent field actions, the involvement and acceptance of the group, which facilitates communication with the inhabitants, which is a pledge of success for subsequent actions. Field games are determined by creativity, and therefore their number can be infinite, but great emphasis must be placed on their preparation. For these methods, play scripts can be drawn up which can be used in more or less any location.

Measuring community activity through actions, small-scale interventions, community building.

After the knowledge acquisition process, which focuses on introductory field exercises and localisation, it is necessary to permeate the process of localisation through field actions and small-scale interventions that contribute to localisation. It is a matter of defining the precise structure, themes and steps involved. The basic principle is that the success of information gathering and community involvement can be achieved by building on the success of certain steps.

First of all, the activity and composition of the local communities must be known, so that later pilot actions aimed at working together can be carried out with groups that show an interest. Community activity can be assessed through a playful method that can be used to gauge the activity or passivity of a local community and can also be used as a community-building method. In most cases, these community-building games are accompanied by the implementation of a built installation, as it is easy to initiate a dialogue with local people through the means of architecture. These actions can be used to raise awareness, promote acts of inclusion and create dialogue. They can also be integrated into the work process as an independent design task, as the exact conception of a space installation is an exciting design task for the architects (students) involved in the project. It is not just a matter of designing an installation and then implementing it, but also of identifying well the sub-areas that the designers can address questions they would like to know from the locals. This information can help to shape the design programme, to rationalise its development.

Chapter 1.2. Presentation of the Tatabánya project (case study) – presentation of space games and two installations

Teaching method: exemplification, case study

Duration: 60 min

Space play scenarios

“Find your point of view!”

The game is played using videophones. Pairs “compete” with each other to find surprising views and features of the location. We know our surroundings from typical perspectives, but less so from hidden features. This game draws attention to spatial and material phenomena that are hidden or even right in front of our eyes. First, one member of the pair looks for a viewpoint in the scene that he or she judges his or her partner to have difficulty recognising. In the process of searching, his attention is drawn to parts of the space that he would probably never notice on his own. The spatial position found is photographed with his phone. Returning to the starting point of the game, he hands his phone to his partner, who sets off to explore the image on the display. The searcher also analyses the location with focused attention. If he manages to discover the image, he takes a picture with his own device so that the two images can be compared at the starting point. An exchange then takes place.

“Description activity”

In addition to learning about local history material, the local level, the local history layer, always provides something new that can feed back into the design. This information can be collected using the tools typical of sociological surveys (interviews, questionnaires), but also in connection with the games of space, since these stories are often linked to specific spaces. The primary aim of the game is therefore to collect local stories told by the people living in the area and linked to their environment (street, square, flat, roof, whatever). The members of the group approach the people in the area individually and have them tell a typical story. Once each participant has returned with a story, the act of storytelling can begin, which can also be accompanied by play. Lessons from the stories can provide valuable information.

“Movement and space”

Exploring space through movement exercises can be an exciting experiment in learning about space. It unlocks the closed channels that often inhibit creativity, expands the cognitive instincts, and opens up a wide spectrum of senses. In many cases, the elaboration of this methodology requires the assistance of a professional in movement arts and movement therapy. His leadership role provides security, dissolving the barriers that are inevitably in place in our entrenched areas of functioning. The essence of these exercises is not based on the training of movement, but rather on the perception of the relationship between space and people.

“Message Wall installation”

The aim of the installation is to initiate community interactions that can be used to map out a network of community relations in the living environment. Knowing the community network, the points of activity, is a key issue in preparing, for example, the development of a part of a settlement. To this end, we created a “message wall” installation by reinterpreting a disused, dilapidated newsagent’s stall. We wrapped the structure’s crumbling pillars with construction site marking tape, transforming it into a highly visible, eye-catching, aesthetic object. The walls of the building were covered with open envelopes, each apartment of each staircase (house) was identified by an envelope, thus highlighting the housing stock. On this surface, it was possible to send a message to anyone living in the area (friend, enemy, a girl from the next staircase who I used to see from the window, etc.). The messages, which could be texts, objects, anything, were placed by the senders in the envelope where they wanted to send the message. By the end of the day, the envelopes we had addressed were a good visual representation of the network of the local housing community. The action illustrated the problematic nature of the act of inclusion, the fact of social isolation in Hungary, and the need for community

“Wall of cards installation”

Our action took place in the area where services are concentrated in the center of the panel. Here too we sought to engage with residents through the creation of an installation, this time to explore architectural needs. In an alley-like space, we created a “marble” wall, where we also used the awareness-raising tool to get closer to the residents. A series of questions was given to people passing through the area, asking them what they felt was most lacking (community garden, running track, market, etc.). During the dialogue, we collected almost 400 answers, which we visualised on the “mapping” (the answers were marked in colour and placed on the wall), which, in addition to being an aesthetic experience, also provided information. From this, subsequent discussions could be initiated with the interested parties. The activity was quite high and the analysis of these experiences helped to define the design programme.

Chapter 1.3. Pietralata project presentation

Teaching method: exemplification, case study

Duration: 60 min

Both case studies are related to the periphery of Rome and therefore focus on architectural and social problems specific to the urban periphery. Of course, the issues related to the urban periphery are unique, so that a knowledge of the urban architectural and social transformation of Rome is necessary to understand the case study experience. Rome’s population has increased 12-fold since 1870 and its urbanised area 50-fold. The city witnessed the frenzy of imperial demagogy: thousands of families were forced to leave their homes to build neighbourhoods representing the new empire, it witnessed an unprecedented demographic explosion thanks to the labour force coming from the South, it witnessed the destruction of private investment on an unrelenting scale (ca. 6,000 hectares of development at a time), witnessed real estate speculation with the tourism boom, which led to the creation of illegal building stock and then to squatting and protests. Rome’s periphery was rapidly emerging, bringing together all the problems of housing (urban, architectural, social). At the same time, there was a shift in architectural thinking that put the problem at the centre, making the periphery part of architectural thinking. The problem of the city and urban space has acquired a distinctive importance in the discourse on contemporary culture. The periphery in this sense is no longer a periphery. The awareness of the different, specific character of place has become important. Groups led by architects were formed and began to work in the field, which began to deal with suburban dormitory cities, recognising the social problems arising from the lack of infrastructure (lack of administrative functions, education and other services, etc.), from the way problems were dealt with at the bureaucratic level without any knowledge of the real deficiencies. It was recognised that rapid growth had led to the juxtaposition of completely different, alien functions and uses, and the squeezing together of different social groups (classes), leading to segregation. At the same time, they recognised the value of the periphery, the potential for spatialisation, the value of non-homogenised diverse architecture, that alternative cultures and organisations can emerge from below in such an environment, that there is potential in the absence of control by power, that overall the periphery has a repercussion on everyday urban life.

Pietralata is the area bounded by the ring road, the railway line, the river Aniene and via Tiburtina. Its history dates back to around 1920, when soldiers returning from the First World War were given 700 hectares of land by the state to settle there. In 1936, Mussolini’s policy of evacuating the city centre swelled the population of the area, and barracks were built. In the 1960s, social housing was built without infrastructure. By the 1980s the “Colosseo” was built and mass squatting began.

It was in this architectural and social context that the group linked to La Sapienza University started to work, carrying out research, mapping socio-architectural conditions through fieldwork, preparing projects with citizen working groups. The group focuses on developing the capacity of local people to organise themselves in order to create a democratic system of intervention that transcends bureaucracy.

2. Site recognition with site-specific installations in natural and urban environments

Chapter 2.0. General topic introduction

Teaching method: lecture

Duration: 30 min

The natural environment is a specific medium for spatial perception. The basic references that define the built environment, such as scale, dimension and distance, do not apply. To characterise the landscape, the observer is forced to resort to abstract concepts such as density, absence, infinity, etc. Abstraction also determines cognition: non-objective, personal cues help. Small-scale interventions in the landscape can contribute to a better understanding of these architectural concepts. The relationship between the landscape and the architectural object can be analysed through them, and at the same time the system of relationships can be interpreted. The design of the intervention always precedes its creation, which brings it closer to the problem under study and narrows its scope. It does not matter what we are curious about, how a spatial line works in a dense forest, or how much the scale of the intervention in an endless dry lake bed already affects the space. The aim of the interventions is to get closer to the landscape, to understand the dimension, to represent and magnify the phenomenon caused by the coexistence of landscape and object.

A parallel can be drawn between the natural environment and the urban environment, if we approach it from the point of view of scale. A dense urban environment is often perceived as a mass, a multiplicity of details coming together to form a large whole. It is also a natural urban phenomenon that when we walk in the city, as in nature, we perceive only large patches, we do not pay attention to the small, the hidden. In the urban space, a moat can be as scale-less as a mire in a lake bed. Our built environment contains many spatial situations which, by situating them, art can emphasise the specific qualities of a space. These qualities are often hidden from the viewer or, because of their familiarity, lost in the complexity and colourfulness of the complex spatial structure. They are used to attract attention, directly or indirectly. Starting from these assumptions, we consider and analyse small-scale intervention as a means of promoting place recognition. The intellectual layers (historical layer, cultural layer, layer of individual and community consciousness, etc.) deposited on the site, on the urban environment, which are deposited as tangible forms, as physical projections on the surface of urban space, ensure the uniqueness and non-repeatability of site-specific installations. The possibility of infinite situations offers a corresponding infinite use of means, which results in a colourfulness of methodologies.

Our basic hypothesis is that small-scale interventions “in-situ” help to learn about place and at the same time model the relationship between landscape and object.

Chapter 2.1. Site recognition through site-specific installation – natural environment Jimbolia

Teaching method: exemplification, case study

Duration: 60 min

The workshop was limited to the practical implementation of the basic hypothesis, trying to prove it experimentally by systematically drawing conclusions from the exercise. During the first site visit, we identified a place with general landscape characteristics such as the lack of a point of alignment, the lack of scale, the barely tangible dimension, the notion of barrenness in the natural landscape. These landscape characteristics were most evident in the dry lake bed, and its atmosphere distinguished it from the surrounding landscape types. We tried to approach the character of the lake bed first by tactile cognition: walking around the lake, walking in the lake bed, unexpected sampling. This was followed by the classic design phase, but only project outlines were sketched out, taking into account what ‘building materials’ were available. It is not negligible for the method that in many cases the interventions were decided by searching (wandering) around the site, since the aim was precisely to get closer to the site through the practice of ‘building’. For this reason, most of the workshop was spent on site, constantly ‘building’ objects. We made shad-patches with red yarn as a landscape prosthesis, shad-covering with a coherent surface (sketch pauses) as a negative landscape prosthesis, line-like imagery by highlighting the dried mud-cubes of the lake bed, then at night, mud-grid delineation with light, a visual game of here-red-where-red-red creating a mismatch of proportions (cardboard surfaces with brick proportions), other interventions suggesting a loss of proportion as in the Italian Riviera (small cardboard surfaces and the mud pattern). All interventions were temporarily “built”, none remained part (or not-part) of the landscape as the method implied. We examined the relationship between the constructed object and the landscape, drew conclusions from the view, documented and then ‘dismantled’ it. It was not a question of presentability, of extracting so-called ‘artistic value’, these objects were a means of cognition, of investigation. For this very reason, we consider the documentation of the interventions and the evaluation of the experiences gained to be a phase that is not at all incidental to the methodology. It is assumed that the workshop experiences will be incorporated into the design thinking, in particular in the definition of the design programme and the scale of the planned building, and in the selection of the building site, and will influence the designer’s decisions in this respect, i.e. the workshop experiences will feed back into the design process.

Chapter 2.2. Site recognition through site-specific installation building – urban environment Budapest – Nanoinvasion

Teaching method: exemplification, case study

Duration: 60 min

The city, in the case of this study Budapest, can be understood as a rather complex spatial and material fabric. The spaces of the everyday, the spaces that are constantly in view and thus paradoxically hidden, are apparently not challenging to explore. It is the lack of perceptions of space and reactions to them, which arise from urban existence, that produces these hidden spaces. Their concealment is not physical, since they are always in view, but they are not endowed with the quality of hidden treasure, since they are characterised by ordinariness. So the question arises: if these places exist and yet they do not, how can they be shown in a way that preserves their basic characteristic, the image of hiddenness? Is there a method of intervention where the means are deliberately minimal, tailored to their insignificance, yet still able to have an impact?

One way is certain. If the result is always to have an effect in covertness, i.e. to be covert.

First of all, the sites must be discovered and found. Little details, gaps, barely noticeable but astonishing spaces, abandoned objects, situations that need to be interpreted. It must be confessed that to do this, the veil of perception that the city’s constant impulse has imposed on the senses must be shed, to become, if you like, a ‘seer’.

The case study is the project Nanoinvasion, a game for urban explorers, realised at the Placc festival. Hidden, and therefore astonishing, interventions could be discovered all over the city using a map or a gps. Some well-known, everyday sites in Budapest were barely visibly disturbed by the creators: details were transformed, added to (a mosaic addition in the tunnel, the reconstruction of a ledge from found material), polished (bike storage from mechanical nodes), architectural details were revealed from their hiding place (a Danube water level meter). The means of intervention were deliberately minimal and adapted to the insignificance. The result is therefore never blatant and remains hidden after the festival. The joy of discovery awaited the open-eyed and the initiated, the participants in the Nano Invasion game. The basic rules of artistic geocaching are similar to those of the popular treasure hunt game. During the Nano-invasion, however, the challenge was not to find a chest, but tiny intervention points using a traditional map or GPS coordinates.

3. Building recognition with site-specific installations

Chapter 3.0. General introduction

Teaching method: lecture

Duration: 60 min

Since the second half of the 20th century, the prominence of place in the history of architecture and art has been growing. In parallel, the perception and understanding of buildings has become more complex. Whereas in the historical period the canonical stylistic features were dominant, and then in the early 20th century, in the modernist period, the details derived from function, since the 1950s a more complex interpretation has emerged, whether in the design of a new building or in the understanding of an existing one.

In contemporary architecture, the role of place and space goes far beyond the geographical context. The building, the social, historical, economic context of the place, the existing details, banal or unique situations can all be attributes that can be a defining point for architectural intervention. This phenomenon also applies, of course, to existing buildings, and it is therefore important to understand the context and to explore it in addition to the objective parameters in the case of alterations and renovations.

In introducing this topic, it is important to understand the development, history, process and prominent examples of the significance of place, as well as the contemporary buildings and design methods in which this kind of contextuality is prominent.

Chapter 3.1. Defining space by its most relevant characteristics – Atelier installation Montrouge

Teaching method: exemplification, case study

Duration: 40 min

The starting point for the studio installation was two independent spaces:

an apartment used as a studio and a garage awaiting demolition as an exhibition space. The installation was a reflection on a question: can one space be evoked by revealing certain characteristics of another space. This question required a creative process that was logically easy to construct. It is necessary to reveal the properties of the space to be presented, to explore in parallel the space of the implant, to choose the priorities of the properties that can be presented, to find the appropriate means to do so. These steps, of course, as in any creative process, interact, sometimes requiring steps backwards. Here it was no different. Of all the spatial qualities of the studio, its heterogeneity, its varying ceiling heights, its complex plan, its large northern overhead light were the most striking. The light streaming in from the overhead light fixture added a continuous homogeneity to the clutter of an otherwise complex space. It was this duality that most characterised the space.

The exhibition space, rearranged from the assembly hall, with its impressive dimensions and the brutality of its raw surfaces, offered the possibility of a fragile, sensual porcelain space, where the contrasts could be even more intensified. The layers of adhesive on the floor, the painted prefabricated reinforced concrete columns, the ornate but rational steel lattice supports, gave the impression of a space that was heterogeneous in its parts but homogeneous as a whole.

One of the possible links between the two spaces was the spacing of the columns, the distance between them, and the approximate internal dimensions of the studio. The transformation of the scale of the hall was thus carried out in the space of the studio, by taking the distance between the columns, which gave a horizontal diagonal in space. The spatial relations were thus superimposed. Scanning the space can be done by taking sections. The sections give a two-dimensional image of the space. Several parallel surfaces, cut in different planes, give an approximate model of the space under study (like a cnc cutter). Using this procedure, a point of space is obtained by cutting out circles of 2,5 m radius from the defined diagonal. By connecting the points, an exciting spatial sketch became visible. A reinterpreted image of space. The cut-outs were connected with black aluminium rods, revealing the floating lines drawn in space with a black pen. A skeleton built from the hidden coordinates of space, brought to life by the dimensions of the hall. Thus the first transformation was achieved.

The experience of birth was the second transformation. A view of the abstraction of the studio in the exhibition space. It strives for pure abstraction, the only resting point within the confusion and impurity of the perceived world, and creates out of itself, by instinctive necessity, geometric abstraction.

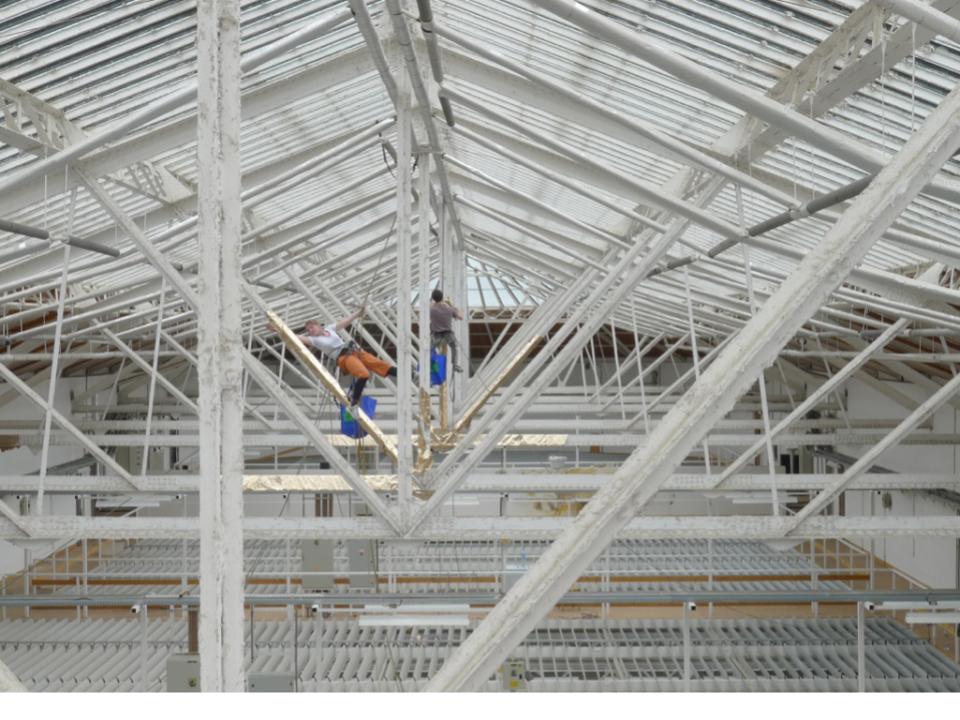

Chapter 3.2. Interpreting space – Kunsthalle

Teaching method: exemplification, case study

Duration: 40 min

The Műcsarnok, Budapest’s contemporary art exhibition space, was built in the 19th century, during the period of historicism, with architectural and spatial solutions typical of the period. Above the large exhibition spaces is a continuous illuminated space of the same size, invisible and unknown to visitors. The installation highlights the interconnectedness and difference between these two spaces. It was not the intention to present the illuminated space directly, but to take the viewer to a deeper level of understanding by experiencing the connections in a reduced, hidden way.

The exhibition space in the classical sense has disappeared, all its references have vanished, and the hall space has been transformed into an exhibition space. This twist, which can be interpreted both spatially and logically, was the starting point for further reflection. They also considered how to best capture part of the unexpected spectacle. What should the spectacle be, is it enough to show the structure of the lattice supports, can a spatial feature be interpreted as a work of art (spatial installation) in itself, what are the limits of interpretability? The unearthly spectacle of the gleam of gilded lattice girders, the lower space homogenized by a transparent foil, was reinterpreted in a striking way. As the intensity of the light changed, the space of the installation constantly changed, new phenomena moved into the space of the Kunsthalle, the passage of time could be perceived as light streamed in through the open glass structure.

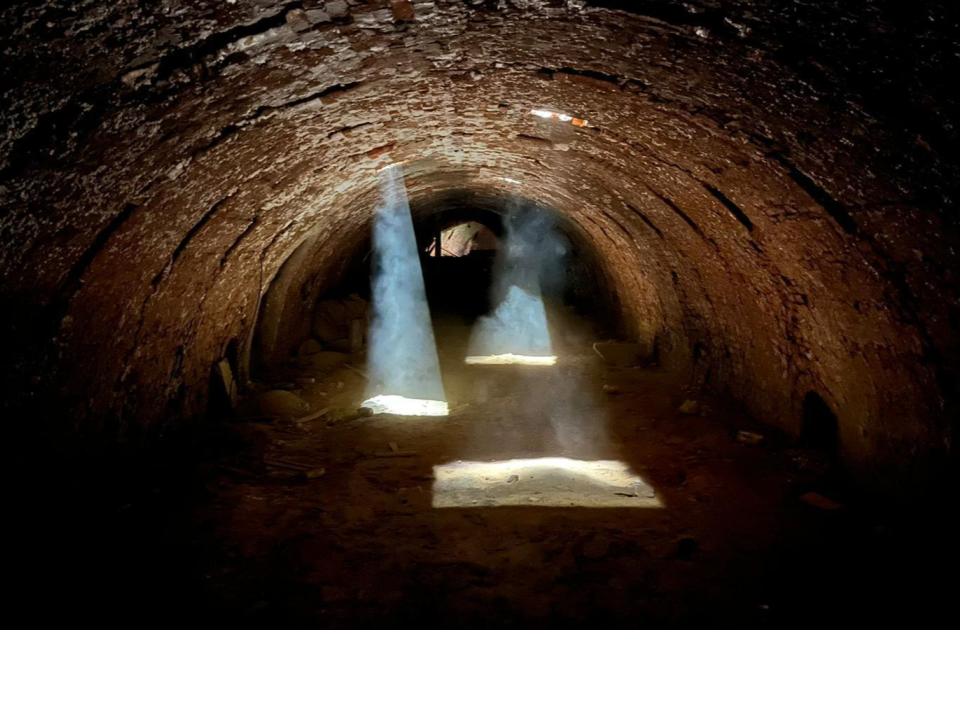

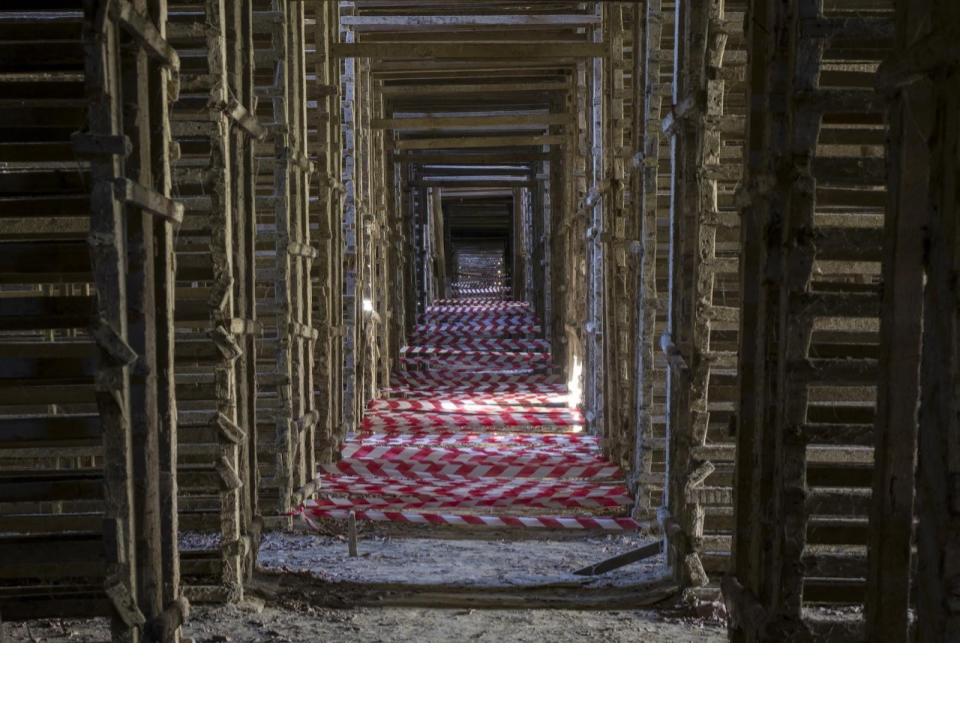

Chapter 3.3. Building understanding with spatial interventions – Terra

Teaching method: exemplification, case study

Duration: 40 min

The Terra Center in Kikinda is a very unique existing building and its surroundings, an iconic complex of buildings of the former roof tile factory, which is in a very good state of conservation. The architectural and structural details of the huge building and the surrounding ancillary structures are an accurate reflection of the former factory operations and its highly functional and rational use. However, to today’s eye, this old function is no longer legible or meaningful, and our perception and reality of ceramics production has changed. The unique, defining parts of the building – the Hoffmann kiln in the basement, the huge wooden structure for drying the tiles and many others – were all strictly the result of the former technology, but with the cessation of production they have now become hidden spaces that are difficult to interpret. These spaces with now forgotten functions have been deciphered and their uniqueness revealed through small interventions. The fireplace of the Hoffmann kiln was evoked with dust, light and reflective surfaces, the upper space cooperating with the fireplace was shown to be connected by a false pillar, and the huge volume of the dryer was emphasised by a ribbon installation reflecting the infinity of the wooden structure.

The interventions brought the former factory building to life, and the observer was left to reflect on the uniqueness of the spaces, their reasons, the old technology, and to get to know the building better.

4. Complex in-site workshop

Teaching method: workshop

Duration: 420 min

During a one-day long workshop, the students can try to make some interventions mentioned during the three sessions before.

They will try to understand the space better, find a specific situation where they would like to interact somehow. It can be an intervention which highlights a certain attribute, interprets a certain situation, helps to understand the space.

References

- Kwon, Miwon 1997, ‘One Place After Another: Notes on Site Specificity’, October, vol. 80, pp. 85−110.

- Perriccioli, Massimo 2016, ‘Piccola scala per grande dimensione’, Techne, 12, pp. 174-181

- Rezsonya, Katalin 2007, Tér és hely az alkotófolyamat és a műalkotás kontextusában, Pécsi Tudományegyetem Művészeti Kar Képzőművészeti Mesteriskola, Pécs.

- Szentkirályi, Zoltán 2006, Válogatott építészettörténeti és elméleti tanulmányok, Terc, Budapest.

- Szentirmai, Tamás 2018, Multifunkcionalitás és flexibilitás az építészetben, Debreceni Egyetem, Debrecen.

- Vági, János 2014, ‘Építés nélküli építészet. Alternatív építészeti és művészeti stratégiák szerepe az építési-beruházási folyamatokban’, Régi-új Magyar Építőművészet Utóirat, 2014/8.

Other Instructors

Miklós János BOROS

Assistant Professor

Tamás SZENTIRMAI

Associate Professor

János VÁGI

Associate Professor

Syllabus

There are now countless technical options for geometrically mapping a site, from traditional manual surveys to automated solutions, including 3D scanning. We can think that we have all the necessary information about the place, relevant knowledge to plan an architectural intervention. However, in addition to these strict geometric parameters, there is also a lot of objective or subjective information related to the place, which may have similar or even more important attributes. Deciphering this information, which is sometimes quite hidden, requires a very different, complex approach, is not really standardised, and is highly dependent on the specific site. The aim of this class is to show certain methods, with which one can understand the space better. The first three sessions present methods in different situations and during the fourth one, the students can try out some of them in a specific situation.

O1.M3 INTERPRETING AND WORKING ON HERITAGE OBJECTS IN THEIR LANDSCAPE

O1.M3.01 Recognition by small scale intervention

Type of format

Lecture & workshop

Duration

Session 1 - 200 min. 60 min lecture 20 min break 120 min workshop, case study Session 2 - 200 min. 60 min lecture 20 min break 120 min workshop, case study Session 3 - 200 min. 60 min lecture 20 min break 120 min workshop, case study Session 4 - 420 min. 180 min workshop 60 min break 180 min workshop

Possible connections (with other schools / presented topics)

DEB O1.M3.02.02 - WORKING WITH THE (INVISIBLE) BUILT HERITAGE

Main purpose & objectives

We believe that a deep understanding and perception of the site of a future building is crucial for the success of it. It isn’t relevant if this space is a natural or an urban site or if it is an existing building. Therefore, before the design process, it has to be a deep research work about the site itself. Obviously there can be different methods for that research, during our class we focus on the in-site research works which are not so obvious. Students will learn methods and approaches with which they can get closer to understanding the most important circumstances and attributes of the site, both objective and subjective. During the process they will see a much broader context of the site, evaluate the different information they collected and to find their personal path which they can follow during the design process.

Skills acquired

Detailed theoretical knowledge regarding colonial territorial planning and the utilization of the grid in order to regulate and subordinate a newly-conquered territory Deep understanding of the physical implementation of the theoretical principles within a well-defined territory, in relation to its economic and social particularities The ability to recognize and interpret physical characteristics of colonial settlements through the comparative analysis of historical plans

Contents and teaching methods

1.0. Site recognition through social inclusion, with community interventions Teaching method: lecture 1.1. Methodology of space recognition, community actions and interventions Teaching method: lecture 1.2. Space games and installations of Tatabánya project Teaching method: exemplification, case study 1.3. Architecture and social problems - Pietralata project Teaching method: exemplification, case study 2.0. Site recognition with site-specific installations in natural and urban environments Teaching method: lecture 2.1. Natural environment - Jimoblia project Teaching method: exemplification, case study 2.2. Urban environment - Nanoinvasion project Teaching method: exemplification, case study 3.0. Building recognition with site-specific installations Teaching method: lecture 3.1. Defining space - Atelier project Teaching method: exemplification, case study 3.2. Interpreting space - Kunsthalle project Teaching method: exemplification, case study 3.3. Building understanding - Kikinda project Teaching method: exemplification, case study 4.0. Complex in-site workshop Teaching method: workshop

Reviews

Lorem Ipsn gravida nibh vel velit auctor aliquet. Aenean sollicitudin, lorem quis bibendum auci elit consequat ipsutis sem nibh id elit. Duis sed odio sit amet nibh vulputate cursus a sit amet mauris. Morbi accumsan ipsum velit. Nam nec tellus a odio tincidunt auctor a ornare odio. Sed non mauris vitae erat consequat auctor eu in elit.

Members

Lorem Ipsn gravida nibh vel velit auctor aliquet. Aenean sollicitudin, lorem quis bibendum auci elit consequat ipsutis sem nibh id elit. Duis sed odio sit amet nibh vulputate cursus a sit amet mauris. Morbi accumsan ipsum velit. Nam nec tellus a odio tincidunt auctor a ornare odio. Sed non mauris vitae erat consequat auctor eu in elit.