O1.M1.03. Transformation and growth within the strict confines of the grid: economy, infrastructure and society – Case study: the urban development of Jimbolia throughout the 19th & 20th centuries

Free

About this course

Chapter 1. Transformation and growth within the strict confines of the grid: expansion within the surrounding territory vs. adaptation of the existing urban structure

Teaching method: lecture – theoretical approach

Duration: 30 min

The aim of this class is to explain the subordinating powers of the grid in relation to the surrounding territory, while also demonstrating its ability to accommodate growth and transformation within the fixed confines of strong physical borders.

This chapter therefore concentrates on introducing students to the different transformation patterns specific for colonial settlements, be it through expansion or through the adaptation of the existing urban structure.

Development patterns based on a pre-existing grid refer to two types of approaches: expansion of the urban form to the (still) unbuilt surrounding territory or densification within the limits of the already built and equipped urban area. As expected, both have advantages and disadvantages and are, in fact, exponents of specific approaches.

Expansion within the territory implies the understanding of the pre-existing plot structure, from the point of view of its physical characteristics (such as shape, size or orientation), as well as its legal-administrative ones (such as nature of the property, form of organization or patterns of government). Overlapping with input coming from the initiator, these features determine the patterns followed by the new extension. Like any growth, it involves the development of existing networks, expenses for the arrangement of public space and regulations regarding the minimum living conditions for future inhabitants. It also involves creating an identity, that can be that of the urban structure that is being expanded or a completely new one.

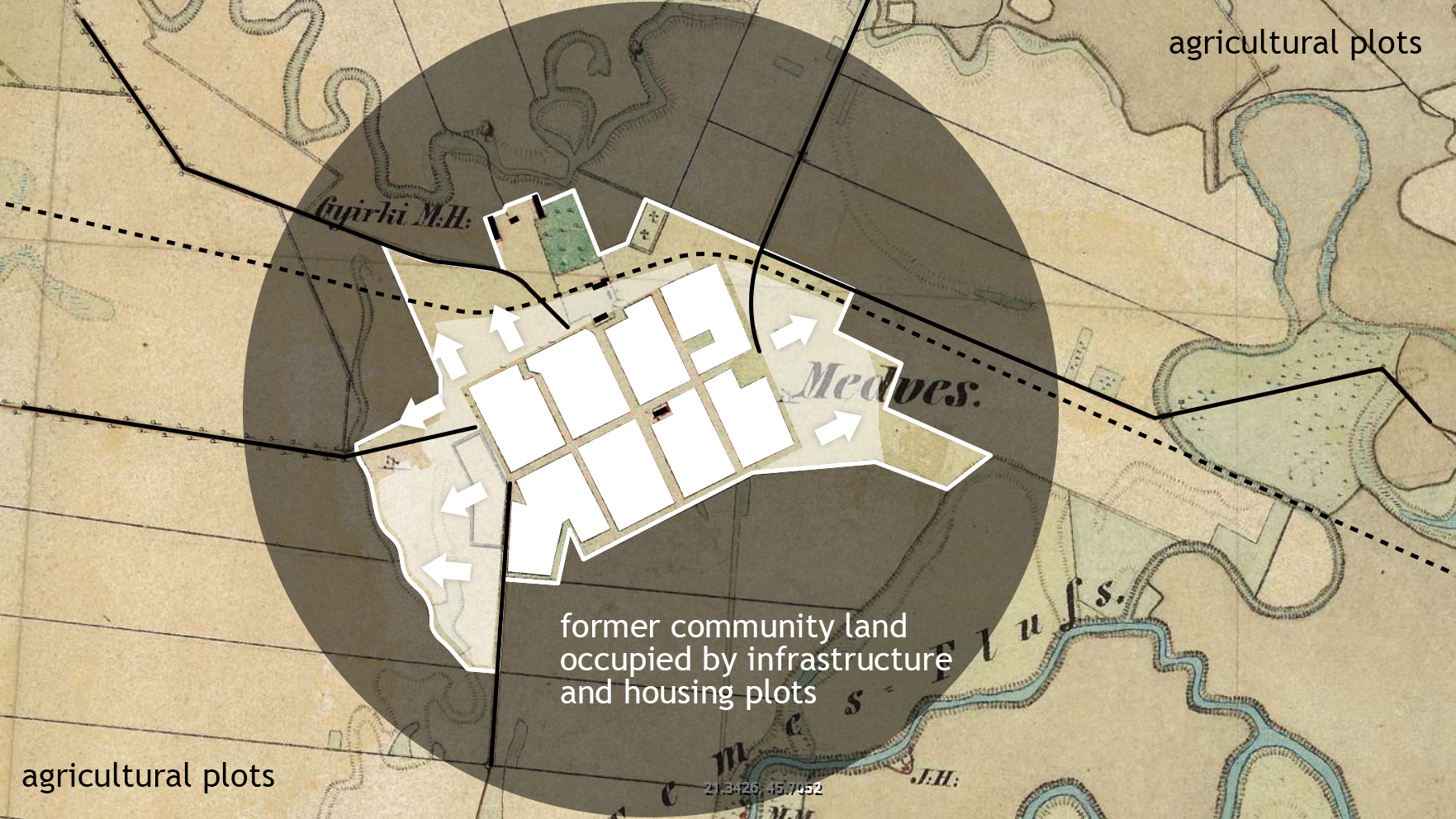

Figure 1.1: Expansion within the territory of a colonial settlement (schematic representation)

Second Habsburg Topographic Survey / Zweite oder Franziszeische Landesaufnahme (1806-1869), retrieved from mapire.eu

On the other hand, densification involves an intervention within the existing tissue, determined as an upper ceiling of overall limits and justified through the affordability of technical infrastructures, as well as the capacity of the local community to incorporate the growth processes within it. Beyond the advantages of economic and administrative efficiency (determined by densification patterns), the success of this type of evolution is determined by the understanding of the initial pattern within which it is integrated.

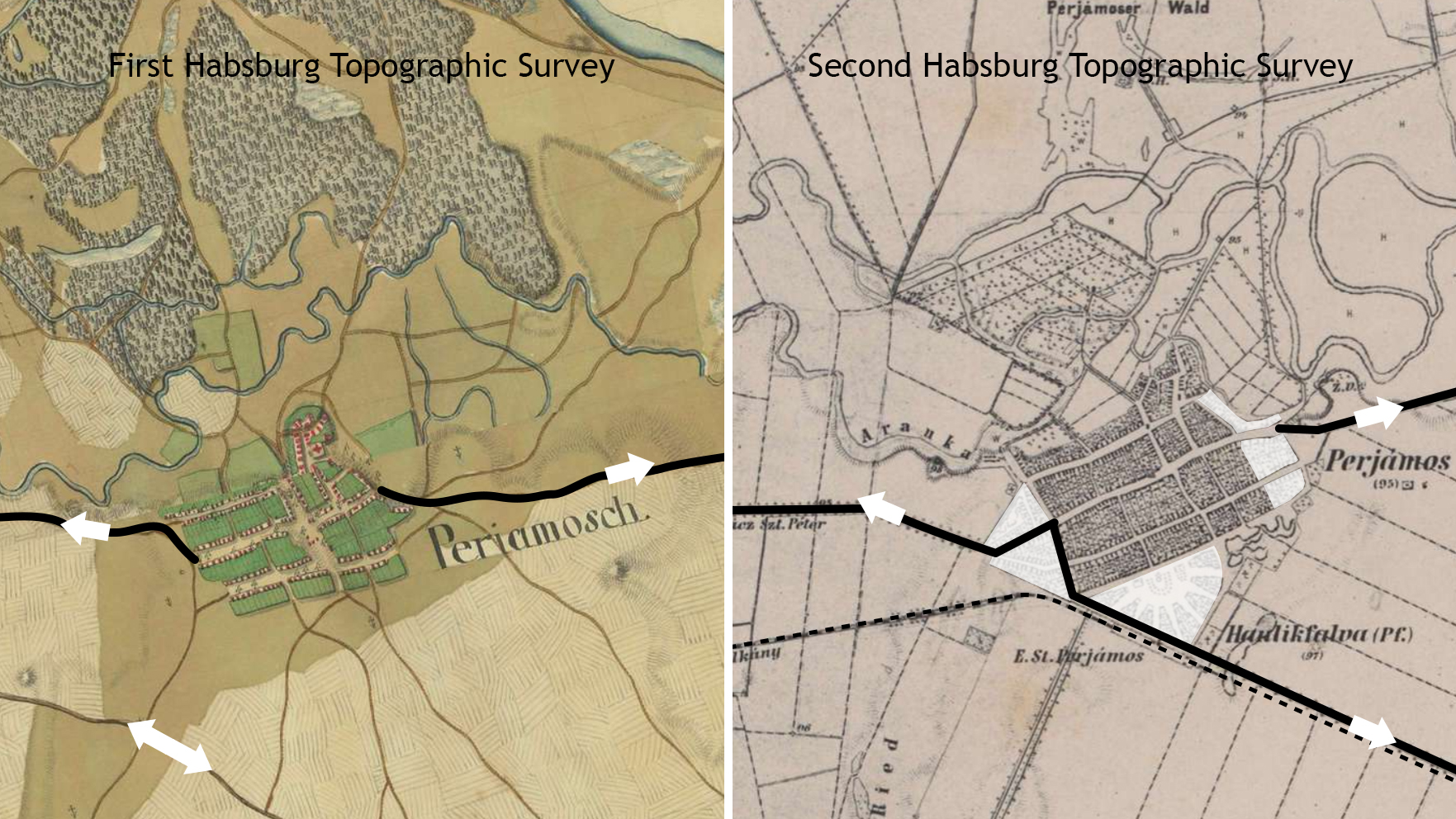

Figure 1.2: Areas of densification, along the main axes, within a colonial settlement (schematic representation)

First Habsburg Topographical Survey / Josephinische Landesaufnahme (1769-1772), retrieved from mapire.eu

Second Habsburg Topographic Survey / Zweite oder Franziszeische Landesaufnahme (1806-1869), retrieved from mapire.eu

The option for one of the two approaches is determined by a series of factors, such as:

-

- the available land resource – whether the settlement does have enough unbuilt terrain in its vicinity, on which it could further develop, as well as the quality and current use of said terrain;

- the imposed time frame – whether the expansion of the settlement must happen rapidly (for example, when the population of a settlement suddenly increases, as a result of a newfound economic prosperity) or whether the development can occur gradually, over time;

- the capacity of the existing networks (mobility, utilities, public facilities, etc.) – to either expand in the territory or to sustain increased densities (of both housing units and population) within the limits of the settlement;

- the financial aspects – whether the administration can afford to build outside the city limits or whether it is more appropriate to invest limited amounts of money and take advantage of the existing infrastructure.

No matter the option, each of the two possible development scenarios come with their own advantages and disadvantages.

As such, the expansion of a settlement within the surrounding territory[1] consumes greater financial and time resources, given the fact that the existing networks must also be expanded outside the city limits, in order to sustain the proper life quality for the new settlers. Moreover, the conformation of the newly built urban tissue is predetermined by the shape, size and orientation of the previously non-buildable plots. However, given that the settlement has enough land resources, its expansion towards the exterior allows for a more impactful development (in terms of both urbanized surface, as well as economic outcome).

As for the densification of the existing built tissue[2], this operation is generally beneficial (and more sustainable), as it does not consume the land resource. Moreover, by increasing the existing densities (up to a certain level), the settlement itself becomes more efficient and the rentability of public investments increases. At the same time, there is always the risk of overcharging the existing infrastructure networks, while also disrupting the established character of the settlement through the new insertions.

However, none of these scenarios can occur without a reason – namely a trigger that generates growth. The following chapter therefore explores the different stimuli that determine the development of a settlement, as well as the distinct forms in which this can be materialized in reality.

Chapter 2. Triggers for growth: the close relationship between economy, society, infrastructure and the urban structure in the case of Jimbolia

Teaching method: lecture – exemplification, case study

Duration: 45 min

The main purpose of this chapter is to further analyze the different stimuli that determine growth and transformation within urban settlements, as well as the impact that they have upon the existing urban structure. These principles are further illustrated in relation to the urban development of Jimbolia throughout history.

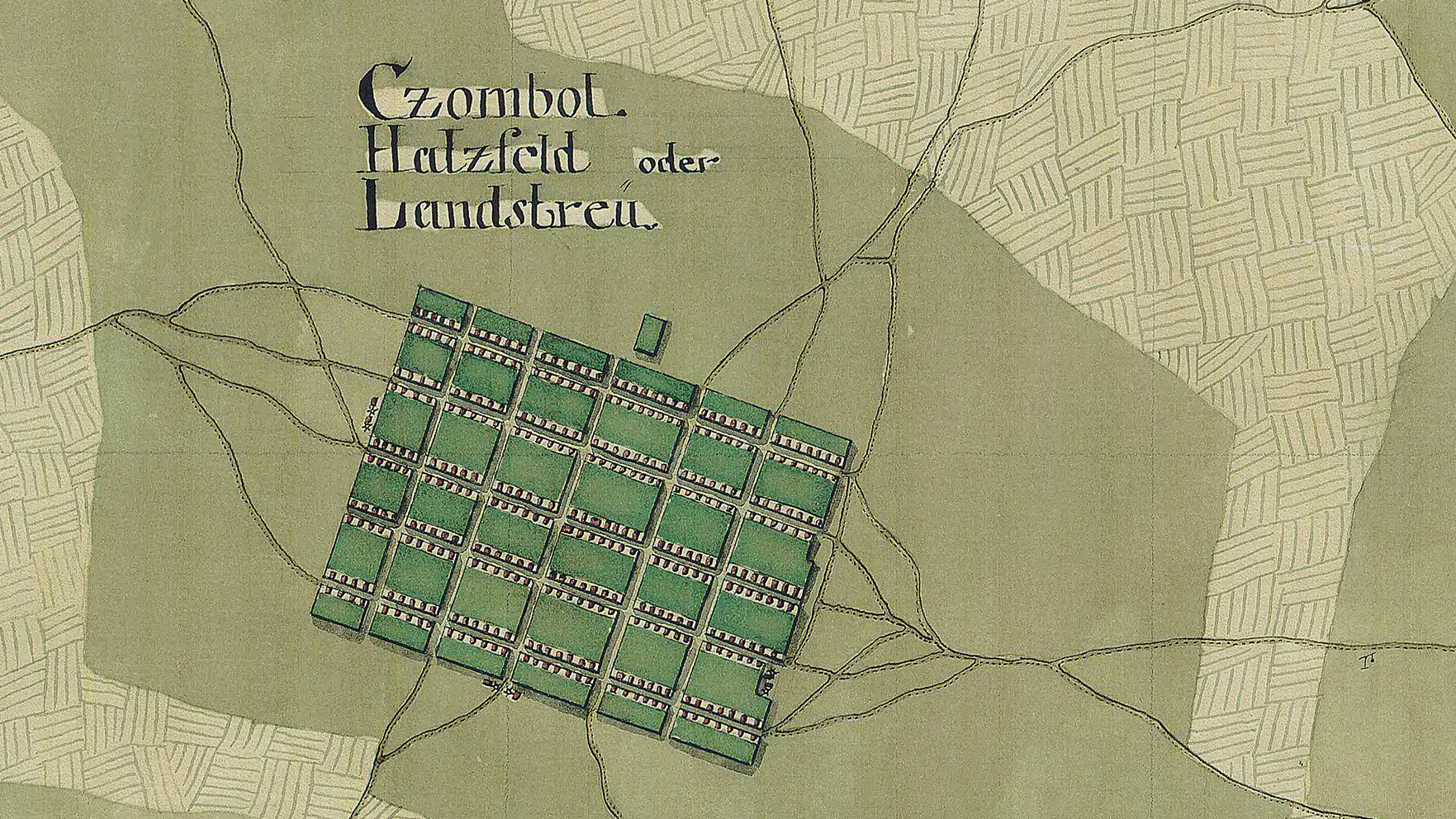

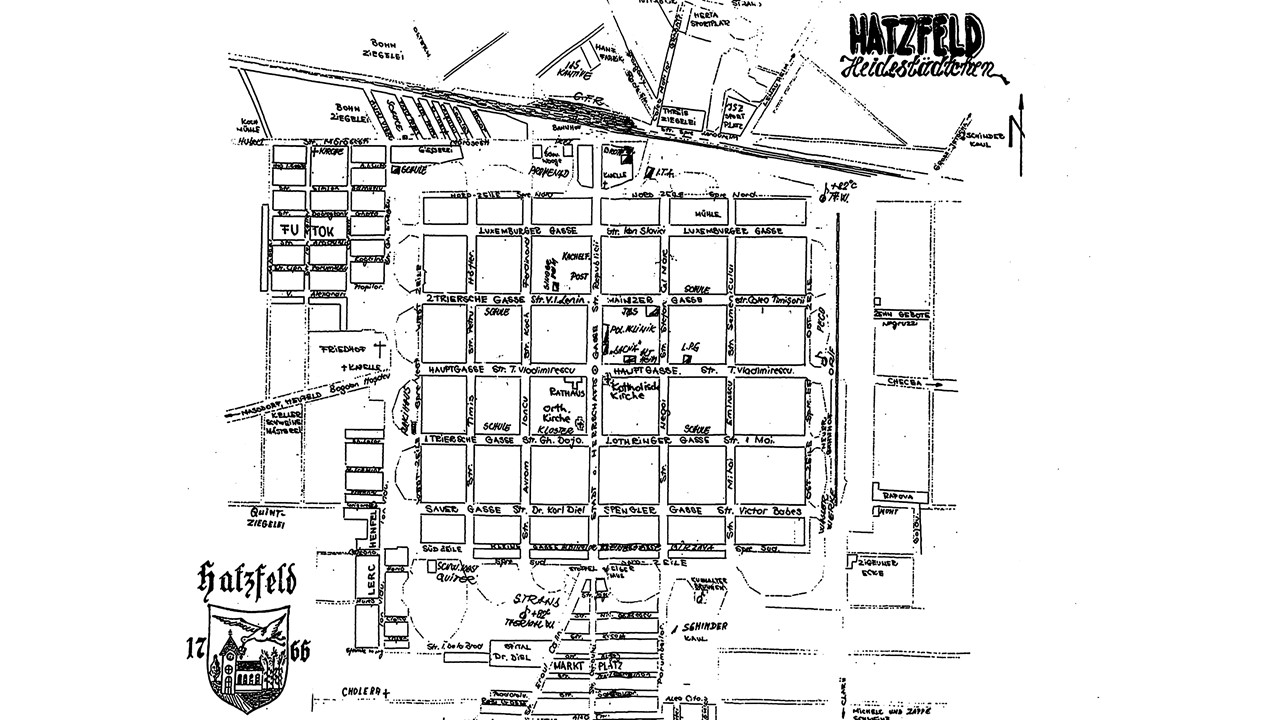

Jimbolia was first certified during medieval times (in 1332). However, its modern history only began in 1766, with the massive colonization of mostly German settlers, implemented by Empress Maria Theresa of Austria throughout the Banat region. It is in this period that the settlement got its grid-like urban structure and colonial features – which developed steadily during the next 100 years, consolidating a strong identity and shaping an homogeneous urban fabric.

At the beginning of Habsburg administration, the locality functioned as a colony of Western European settlers, whose main role was to exploit a potentially agricultural, but still swampy, territory.

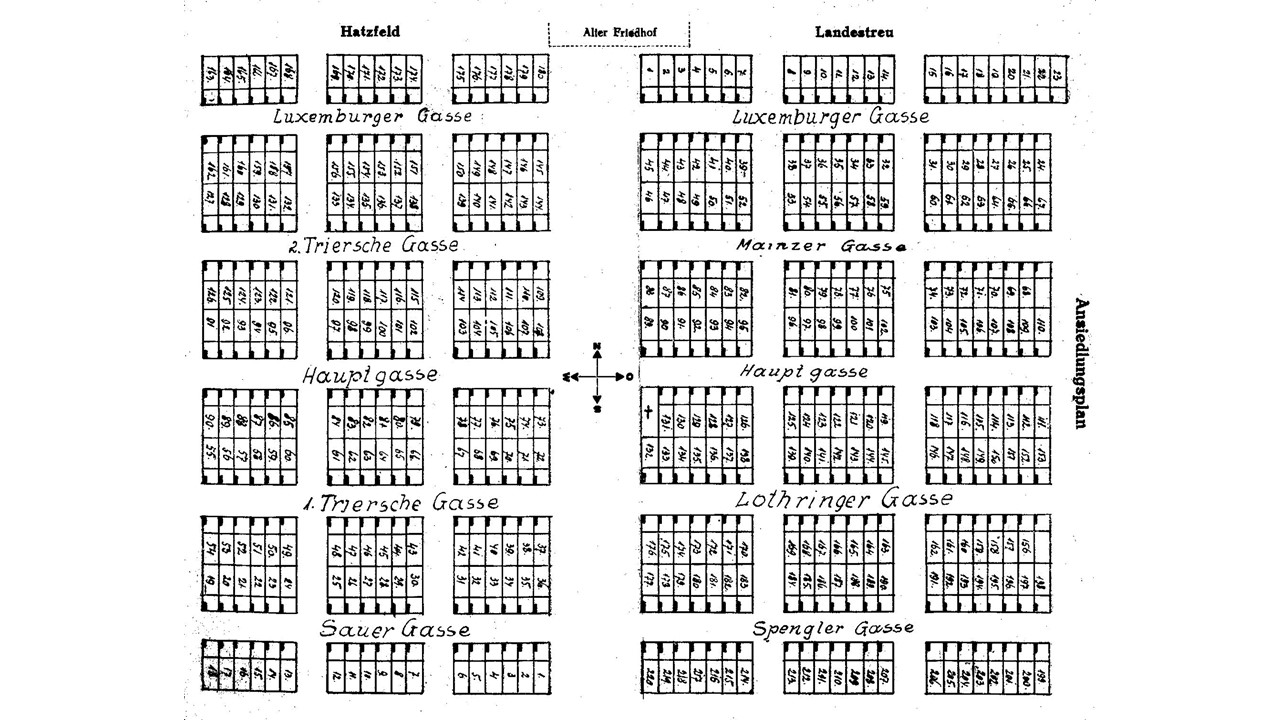

At first, German colonists developed two different settlements, which later joined together to form Jimbolia. Their built urban morphology is organized following a grid-like structure, with cartesian streets and uniform building plots. The two entities were initially separated by a large street, which later became the main axis of the settlement.

Figure 2.1: Initial layout of Jimbolia – made out of two distinct entities, separated by the future main axis of the settlement

Bayerisches Landesamt für Denkmalpflege (2021) KDK workshop, Timișoara

The First Habsburg Topographical Survey – Banat Josephinische Landaufnahme, completed by the Habsburg administration during the second half of the 18th century, sees the two initial entities joined together to form Jimbolia. Following the unification of the two initial settlements, the street which once separated them gradually turned into Jimbolia’s main axis. This happened long before the development of the railroad, when this axis connected the market place (in the south) with the cemetery and its chapel (in the north).

Figure 2.2: Jimbolia in the First Habsburg Topographical Survey of the Banat region – Banat Josephinische Landesaufnahme, completed by the Habsburg administration during the second half of the 18th century – ensemble

First Habsburg Topographical Survey / Josephinische Landesaufnahme (1769-1772), retrieved from mapire.eu

Figure 2.3: Jimbolia in the First Habsburg Topographical Survey of the Banat region – Banat Josephinische Landesaufnahme, completed by the Habsburg administration during the second half of the 18th century – detail

First Habsburg Topographical Survey / Josephinische Landesaufnahme (1769-1772), retrieved from mapire.eu

Over time, Jimbolia has evolved as a polarizing local economic center, producing various goods (such as building materials) and contributing to the well-being of the locals and the surrounding area. Later, with the discovery and expansion of the railways, the connection of the city with the major economic networks became easier, influenced by the main rail route established between Timișoara and Vienna.

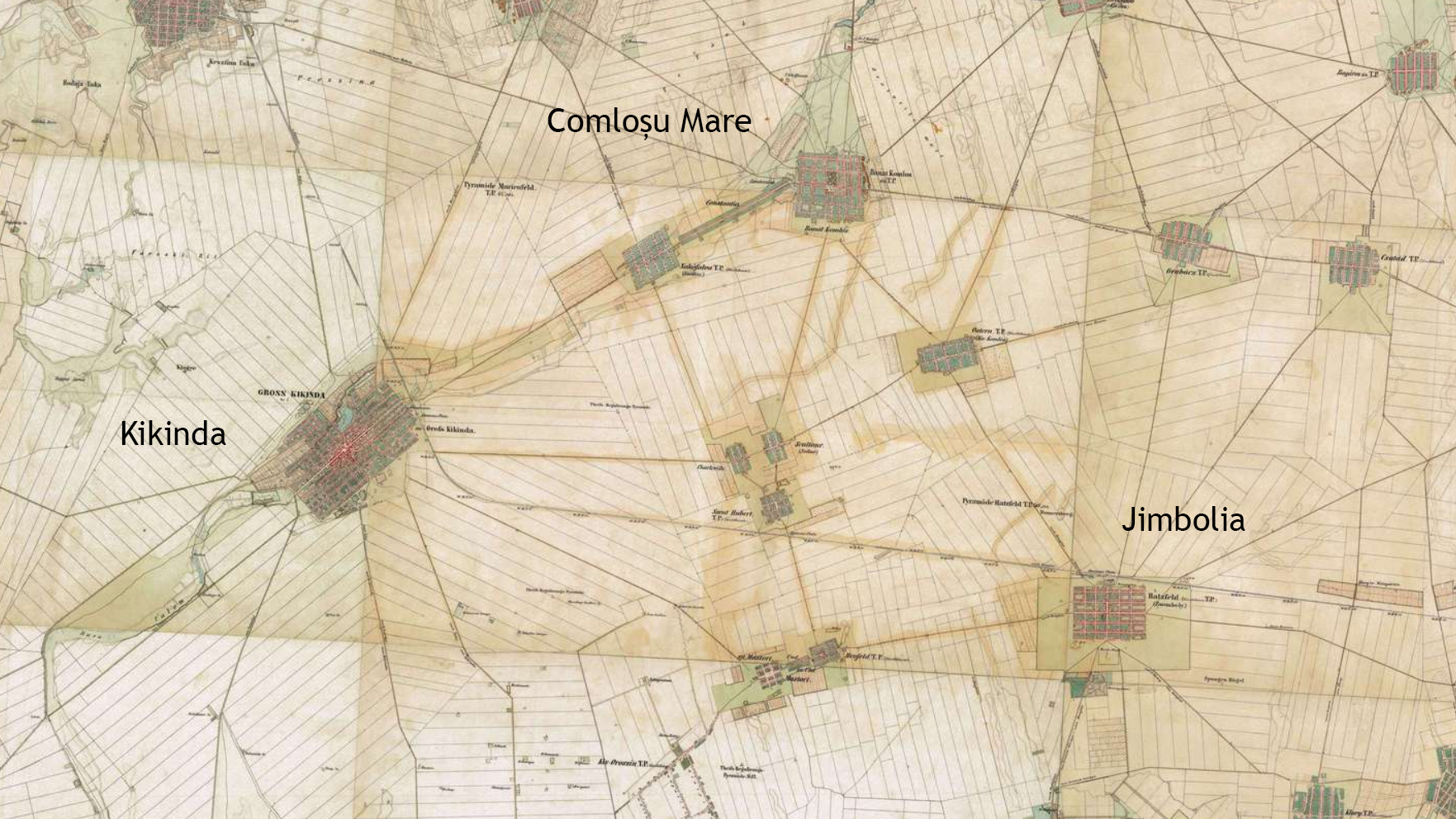

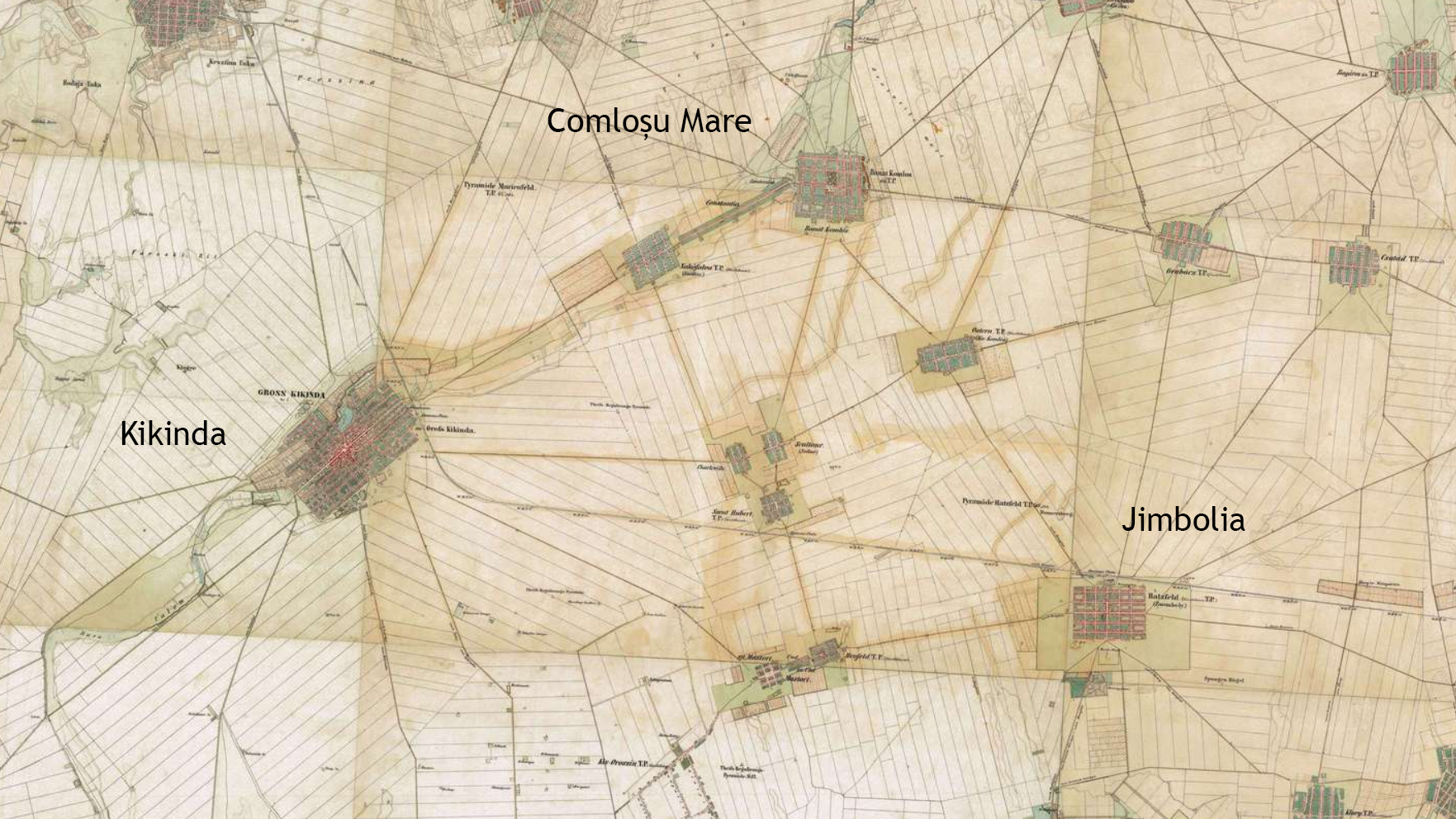

Figure 2.4a: Kikinda, Comloșu Mare and Jimbolia in the second topographical survey of the Banat region – Zweite oder Franziszeische Landesaufnahme, completed by the Austro-Hungarian administration during the first half of the 19th century – ensemble

Second Habsburg Topographic Survey / Zweite oder Franziszeische Landesaufnahme (1806-1869), retrieved from mapire.eu

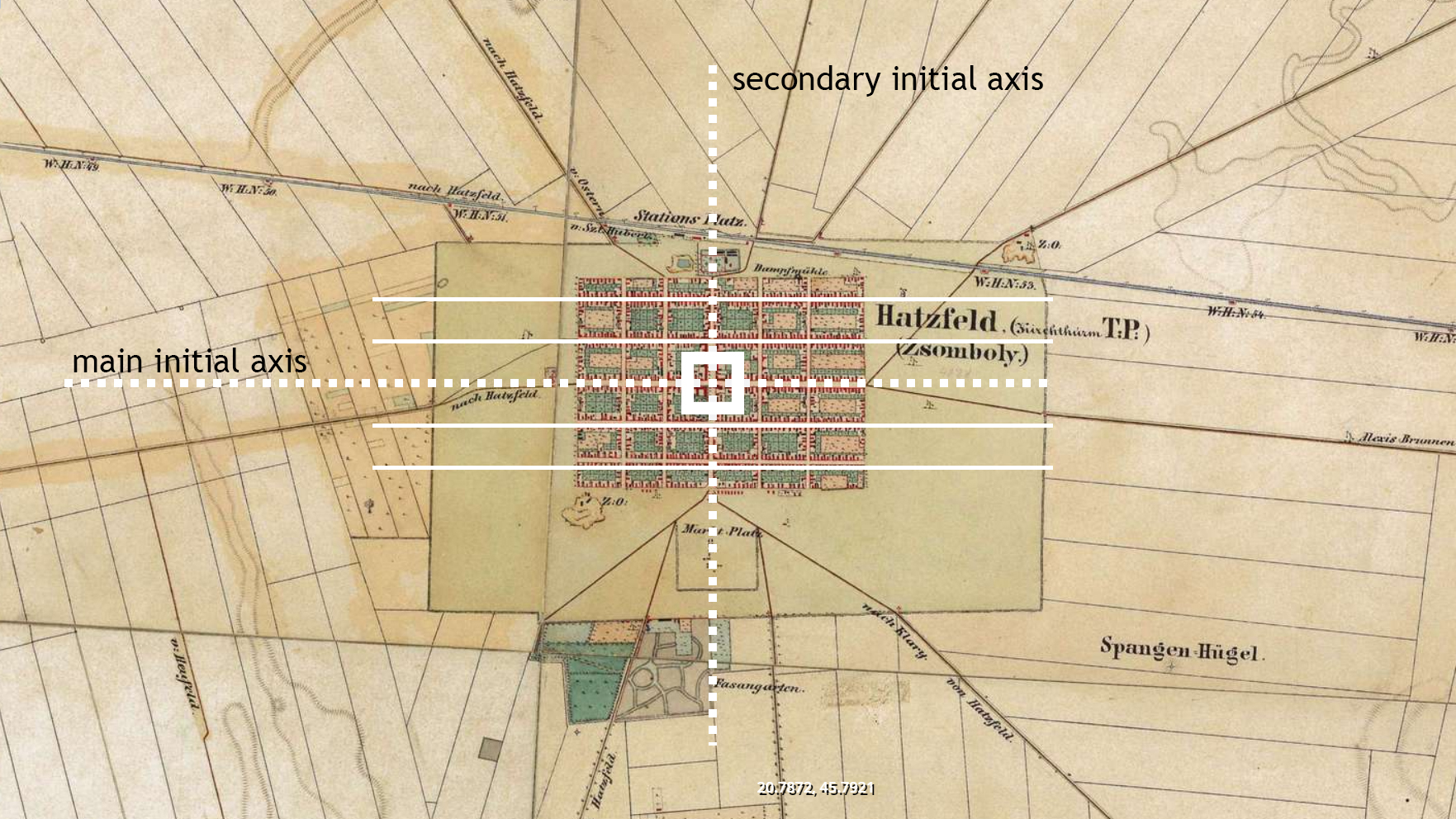

Figure 2.4b: Jimbolia in the second topographical survey of the Banat region – Zweite oder Franziszeische Landesaufnahme, completed by the Austro-Hungarian administration during the first half of the 19th century – detail

Second Habsburg Topographic Survey / Zweite oder Franziszeische Landesaufnahme (1806-1869), retrieved from mapire.eu

This phenomenon occurred during the second half of the 19th century, when a new railroad network was developed all across the Banat region, connecting the colonial settlements with each other, as well as with the two capitals of the Austro-Hungarian Empire[3]. One of these railways borders Jimbolia towards the North and is served by a railroad station, placed in the vicinity of the old cemetery.

Inaugurated on November 15, 1857, as part of the railway connecting Vienna to the Danube and, implicitly, to the Black Sea, the Szeged- Jimbolia- Timișoara railway line, proved to be an invaluable infrastructure asset, greatly contributing in Jimbolia’s economic boom of the next five decades.

Initial planning had this very important railway corridor going several kilometers to the north of Jimbolia, through Sânnicolau Mare, Comloșu Mare and Lenauheim. If this initial planning had been implemented one can only assume that Jimbolia’s economic, social and even cultural history would have been different from that which we know today. Enter Count Johann Csekonics, whose large agricultural estate was centered around Jimbolia since the late XVIII century. His lobbying at court authorities in Vienna as well as with the board of STEG (K. K. Priv. Österreichischen Staats-Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft) , and subsequent land donations, proved to be detrimental in moving the rail line to the benefit of Jimbolia and not of Sânnicolau Mare. Csekonics also convinced local land holders to donate their land foreseeing the huge, long term benefits of this donation. STEG was more than happy with this new turn of events as now, they were receiving most of the land for free. It is believed that in doing this, Csekonics also took advantage of Count Nákó’s hesitation in implementing this new transport technology on his lands around Sânnicolau Mare.

With the completion of this railway route, Jimbolia entered a new stage in its development. In its northern part, in the immediate vicinity of the new railway, enterprises, led by courageous entrepreneurs, soon settled. Bohn, who opened his first office in Jimbolia in the area where section C of Ceramics was located, was one such pioneer of industrial development. His example was followed by other ceramic factories, by the Decker and Union hat factories, the small mill and the large mill, (Pannonia and Prohaska), and later on by the button or shoe factory. In addition to these enterprises, sports and recreation facilities also appeared in the vicinity of the Jimbolia’s industrial area, such as swimming pools, football, handball and athletic stadiums.

The development of the locality took place to such an extent that, four decades later, there was a need to reorganize the entire line system, as the old station was replaced with a new one. New lines were opened towards Becicherecu Mare and Pardan. In the eastern part of the town a new railway station was built, which meant that by 1900 Jimbolia benefited from two different stations.

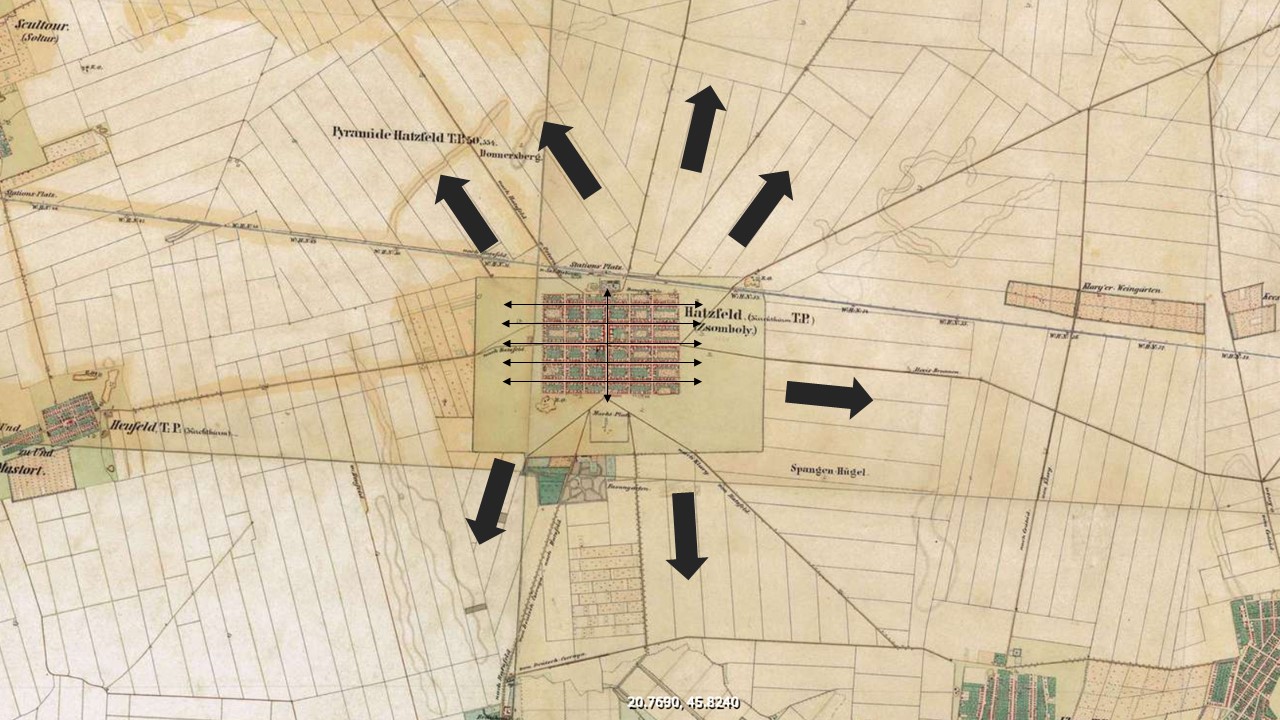

The disruption caused by the industrial revolution, with the development of rail lines, the various ceramic factories and the other infrastructure objectives with productive purposes erected here, impacted the compact urban form of Jimbolia, by encouraging extensions on its various sides.

The town of Jimbolia therefore gradually expanded throughout the 19th century, with the urban form following the shape of the large agricultural plots surrounding the settlement; at the same time, given the strong physical borders created around Jimbolia (in the form of large clay pits- kaule, which enclose the built tissue), one can also witness the growth within the grid – the continuous adaptation and transformation of the urban structure in order to accommodate and absorb the economical, infrastructural and social changes.

Thus, if once the densification of the urban fabric only involved the plots located in the vicinity of the main street, along which a number of urban palaces were erected, the new industries began to develop on the settlement’s perimeter, in an area where the land value (previously only used for grazing) was much lower.

The built tissue therefore expanded during the 19th century, with the urban form following the shape of the large agricultural plots surrounding the settlement. The rectangular tissue gradually occupied the land (pasture) surrounding the existing compact urban form – with the Csitto castle of the Csekonics family also developing in the southern part of the town, in the axis of the main street.

Short Intermission – Csitto Castle

If industry settled on the northern side of Jimbolia, the south belonged to the huge Csekonics estate. The Csekonics family settled in Jimbolia at the end of the 18th century, when they were awarded an exploitation lease for its agricultural lands. Their first mansion, still retaining elements of the baroque fashion, was built at the turn of the 18th century, opposite the Catholic church. It now houses the local town hall. As a recognition of the family’s contribution to the economy of Austro-Hungary, starting with 1864, The Csekonics’ received a hereditary seat at the Upper House of the Diet of Hungary. This sealed the family’s ambition of building a new mansion, on the outskirts of Jimbolia. There, between 1869-1870, based on plans drawn by the famous Hungarian architect Ybl Miklós, Josef Csekonics’ Csitó castle was built. It was designed in the fashion of the time, emulating the English romantic style. The three storey building, (basement, mezzanine and first floor) had 55 rooms. As it was customary, ladies and gentlemens apartments were housed in different wings. Its main dominant feature was a welcoming tower used for the arrival of carriages, and entrance. The castle was surrounded by a 110 hectare English park that was later fitted with a greenhouse for exotic fruits, pineapple, as Duchess Odescalchi recalls, being one of them. A chapel, designed by Artúr Meinig was also built in 1884. Inside it, the Csitó castle contained a wealth of artefacts and furniture pieces from as far away as Japan. The family library amassed 6000 volumes.

Following the partition of Banat as a result of the Paris peace treaty, and the dramatic unfolding of the Hungarian Bolshevik revolution the Csekonics family entered a new period of turmoil and economic insecurity. With their estate now split between three countries, they were gradually forced to abandon their property and seek their fortunes in the west. After several failed attempts of selling their castle and its huge park, in 1937, the remaining Csekonics decided to demolish it, wrongfully believing that they could thus obtain a higher profit, by simply selling its bricks and materials. Few traces of its presence are still visible on site. Parts of it however were repurposed by the local community for various needs. Recovered stone capitals and plinths can still be seen throughout Jimbolia’s public spaces, as silent artefacts of this bygone era. Surprisingly, several stone cladding elements can also be seen in Futok, where local dwellers have used them to refurbish their house plinths.

Figure 2.5: Jimbolia’s expansions within the territory during the 19th century

Second Habsburg Topographic Survey / Zweite oder Franziszeische Landesaufnahme (1806-1869), retrieved from mapire.eu

At the same time, this outward expansion offered certain advantages in regard to the quality of clay, the access to infrastructure or the provision of housing units in a compact system. Thus, in these perimeter pastures, a series of ensembles emerged, combining industrial buildings with dense workers’ colonies, oriented similarly to the 36 blocks of the initial settlement, but built in the vicinity of the factories.

These extensions became the place for densification experiments, in which the plots were structured on the criterion of efficiency and, thus, without providing ample outdoor space – in opposition to the low-density plots of the initial settlement, conceived for complex households, containing living functions, annexes and large gardens. We therefore witness a subsequent colonization of Jimbolia, with the population of these new neighborhoods mostly consisting of workers for the large brick factories.

Case study– The Futok workers Colony

In the northwestern part of Jimbolia, outside the ring of kaules, there is a working-class neighborhood whose existence is closely related to the Bohn ceramic factory.

The Futok neighborhood, as it is called, emerged as a byproduct of industrialisation. It is by all standards a workers colony, with a spatial morphology and cultural identity that sits in contrast to the one visible in the historic settlement of Jimbolia. Futok is also a product of chance. In 1879 the city of Szeged was flooded. With many of its buildings destroyed it was in urgent need of repairs. Large parts had to be rebuilt, and Bohn’s factory in Jimbolia, only a couple of kilometers away along the rail line, rose to the occasion. The high demand for tile and brick, however, far exceeded Bohns production capacity at the time, as most of Jimbolia’s inhabitants were still farmers or craftsmen. Seeking this new much needed labor force, Bohn encouraged families from the flooded areas to take refuge in Jimbolia and work in his enterprise. These colonists were the first inhabitants of the neighbourhood, thus greatly increasing in numbers Jimbolia’s proletariat. This phenomenon was not without consequences as they were joined shortly by former agricultural laborers, gradually leaving the Csekonics estate, disgruntled by their low wages. This sparked a new rivalry between the old class of estate owners and the new class of industrial entrepreneurs.

Initially, Futok’s dwellers lived in barracks. The first proper houses in the colony appeared in 1892, as land near the factory was parceled out and sold to the workers of the enterprise. The evolution of the neighborhood was directly linked to that of the factory, with positive changes, especially following the direct investments and explosive turnouts of 1907, 1908, 1911, 1912. The urban morphology of the colony is however of great importance, as it was built on plots without proper agricultural gardens. While traditional housing units in Jimbolia were built according to colonial planning and benefited from generous gardens that could sustain a family’s needs, this was nowhere to be seen in the case of Futok. Here, the house occupies half of the plot, the rest being a flower garden in relation to the street. In effect, this spatial condition meant that the Futok proletariat was unable to practice any agricultural activity, even on the smallest scale. Another interesting cultural aspect, gradually developed in time, can be observed in the formal and aesthetic aspect of these houses. They were ingeniously clad by their inhabitants with the many brick products manufactured in the factory throughout the last century, a reality visible today in its patchwork of brick patterns. This was done not only for aesthetic reasons, even though a local aesthetic has gradually been defined in time, but for very practical reasons. The efficient brick, generally used, acts as an extra layer of thermal insulation and as a water barrier.

The most exquisite architectural object in Futok, that literally stuns visitors walking its streets, is the Archangel Michael, Roman Catholic Church, parish church. It can be said, almost certainly, that the adoption of this saint is closely related to the importance of the name Michael in the Bohn family, Michael Bohn senior and Michael Bohn junior playing important roles in the founding of the factory. The brick church was built between 1928 and 1929, opposite to the factory’s headquarters in a flamboyant neo gothic style that would allow it to be not only a place of worship for the neighborhood but also a centerpiece for the Bohn products, a showroom of sorts. Surprisingly, for this complex architectural endeavor, a local architect was employed, Johann Jänner. His design highlights the wealth of ceramic products manufactured in the Bohn factory, glazed bricks of various colors, special detailing bricks, tiles and ceramic decorations. Most of the brick models and tiles used here were later also used in the building of the Orthodox Metropolitan cathedral in Timișoara.

Few people, even in Jimbolia, know however that there is an old Futok and a new Futok. The old Futok covers the area from the station to the Pannonia Mill (FNC), while the new one stretches from the Pannonia Mill to the cemetery.

Figure 2.6: Industrial facilities and workers’ colonies developed around Jimbolia during the 19th century and early 20th century

Nonetheless, the economic profile of the locality also diversified, marking a shift from the initial agrarian settlement to a complex locality, with extensive processing industries and a market expanded throughout the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Short Intermission: The craft Tradition in Jimbolia

21 guilds: masons, carpenters, locksmiths, gunsmiths, shoemakers, bootmakers, hatters, tanners, painters, butchers, blacksmiths, tailors, were already present in Jimbolia by 1823.

There were several guidelines to be followed regarding apprenticeship, with rules clearly stated in a statutory document. Guilds could not discriminate against applicants based on their religious affiliation. The probationary period of apprenticeship lasted for 6 weeks, during which time the person who was initiated into the new profession was not allowed to leave his master, had to behave morally and modestly and was not allowed to spend time at night outside. The master had to behave well with the apprentice and not use him or her for household chores, but only for activities that were related to his craft. If an apprentice left his master for no reason, or was absent for two, three or more days, he was to remain in the apprenticeship for one more week as punishment for each day absent (according to Article 4 of the Statute of 1823). Article 6 obliged the master to teach his apprentice the craft as soon as possible, so that the latter could earn his own food through his work.

In addition to the craft’s cooperative, an entity was set up under the tutelage of which the first Leihbibliothek, or lending public library of the locality appeared. By 1925 this library had more than 1600 titles. This entity also laid the foundations of a music society, Gewerbe-Gesangverein, which spread the cultural identity of the town even in remote areas. On May 28, 1893, a 42-member choir was established. From 1907 it was conducted by Josef Linster. He has won numerous awards in Lugoj and Szeged, having successful performances in Vienna, Timișoara, Arad, Lenauheim to name just a few. Eventually, after much training under Linster, the choir was able to perform entire operettas, such as: Zweierlei Tuch, Der Rastelbinder, Dreimädelhauses, Csárdásfürstin.

These cultural activities of the craftsmen led to the development of the Sängerheim building, known as the craftsmen culture house. The building was inaugurated on June 30, 1929. On this occasion a special concert was held, in which the conductor Josef Linster led a choir of 120 people and an orchestra of 30 instrumentalists. During the communist period, it functioned as a meeting room of the “Viitorul” Crafts Cooperative.

On April 2, 1885, a committee dedicated to education was set up, which on April 29 laid the foundations of the apprenticeship school. It maintained a continuous existence for over 7 decades. During its first first year, 139 students were enrolled in the gymnasium, divided into 2 classes. From the year on until 1933, 9945 graduates were trained in 56 different trades. 5588 were from Jimbolia, and 3457 from over 10 other neighboring villages and towns. Exhibitions were held annually showcasing these graduates’ best outputs. They were awarded with prizes in money as well as books. The winners would later on take part in similar competitions in Timisoara, Budapest or Bucharest. In spite of its results, the school was not forign to hardship however: underfunding, difficult conditions in the boarding school, the effects of the great war and of the partition (a time during which many workshops were closed), took their toll. In 1933 the school had only 55 students. However, in the period between 1925-1927, out of the 12122 inhabitants of the city 1195 were related to the craft activities.

Several figures are worth mentioning, such as Peter Schwarz, a prosthetist who was awarded several times for his work, even in Paris in 1910 and in Rome in 1912. Some of his diplomas are in the Banat Museum.

As Jimbolia’s petit bourgeois and proletariat classes grew by the end of the 19th century, new public amenities were gradually being introduced within the circuit of social and public life. The need for recreation, for leisure, specific for these new urban classes, were detrimental in the development of these new public programs: and several swimming pools, and sport facilities soon appeared. These were financed and developed by various local stakeholders, industrial entrepreneurs or communal associations. Two of these, the Threiß Swimming Pool and Bohn Swimming Pool, have set the standard for such public programs in Jimbolia. Both of these were established around the 1920s and 1930s. They were preceded however, even as early as 1900 by a public steam bath, that operated on a differentiated program for men and women. Here, one would find several bathing hot tubs but also a swimming pool used for teaching lessons.

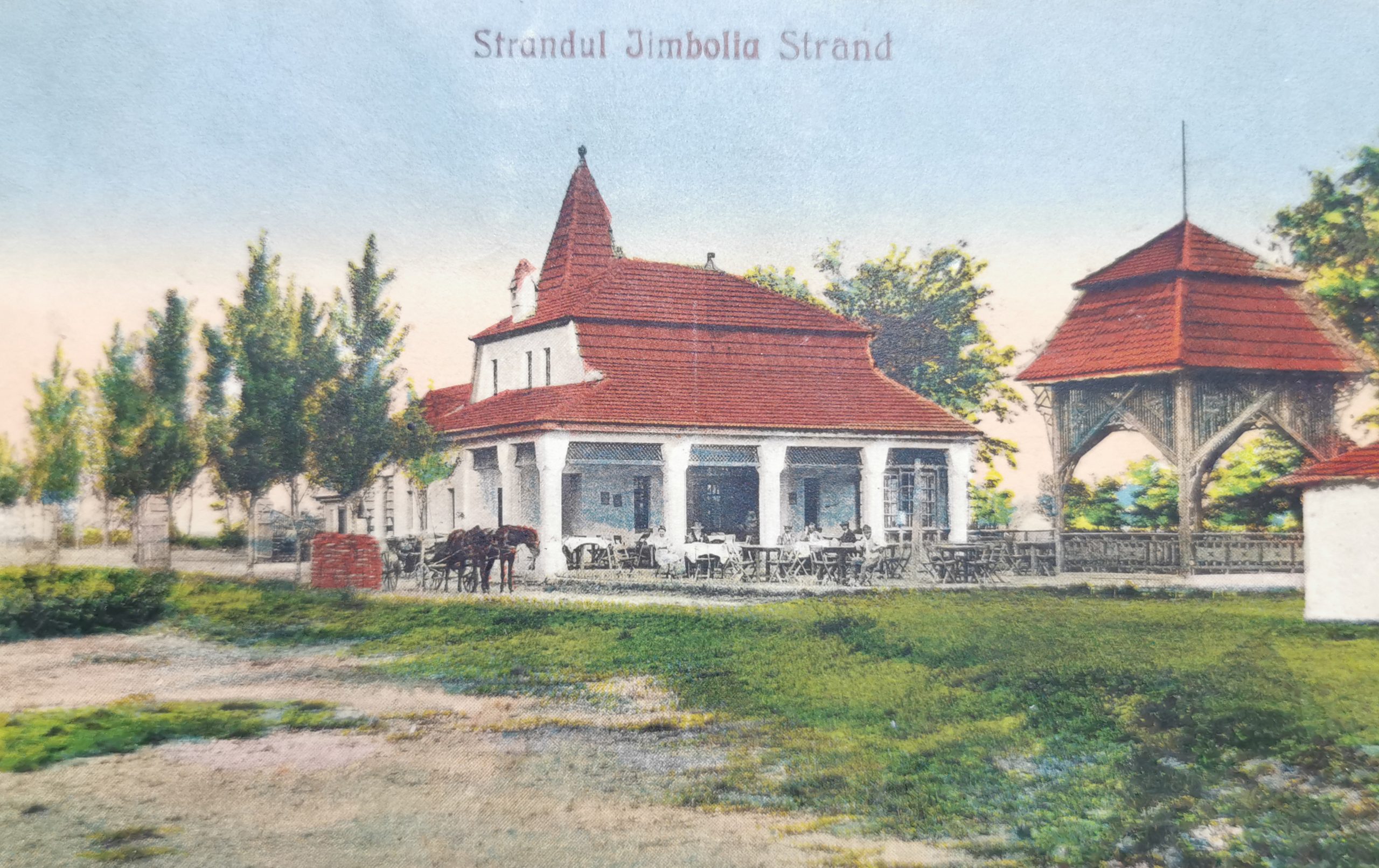

The Threiß swimming pool, built by the Hertha Sports Club, included swimming pools, fitted with changing cabins and a restaurant. It was built in a water-filled kaul formerly belonging to the Threiß factory, hence its name. Within the artificially formed lake, wooden basins, ancored on all sides were submerged. The pool’s restaurant was located in a fashionable building with a high tower and a generous covered terrace surrounding its sides. A light wooden music pavilion, used by local bands, was also built in its vicinity. The pool was frequented mainly by people from the city and the inhabitants of eastern Jimbolia, (3) but regional swimming competitions were also organized.

Bohn’s pool on the other hand, while not far from the Threiß facility, was inside his factory. It also had wood basins submerged in a lake 4 to 6 meters deep. The large pool had the following dimensions: 30 meters long, 5-6 meters wide and 1.2-1.8 meters deep. Outside these basins, swimming was forbidden, a fact made known by several warning signs written in Romanian, Hungarian and German. The pool was divided into two sections. One part was dedicated to factory officials and paying customers, and the other was intended for the company’s workers, who had free access. At first there were 30 cabins on both sides of the pool, but in 1937 another 20 were added on the “royal” side.

The Bohn Pool was frequented mainly by residents of the Futok neighborhood and the western part of the town. During the interwar period, during Sunday’s, the atmosphere was maintained by Fraunhofer’s band from Comloșu Mic. Refreshing drinks such as soda or raspberry juice, beer, wine, sandwiches, croissants, beef steak and sometimes even fish could be ordered. A 100 square meters sandy beach was created next to the lake. Sporting facilities were also present, as patrons could play table tennis, bowl on an outdoor alley, or jump from a 2 meter trampoline. During the month of July, a festival dedicated to swimming and fishing techniques was organized, (3) Francisc Jung, notes that Bohn’s Pool was also fitted with a stage used for various events, a dance floor, a volleyball court, and areas for playing chess or rummy. In 1937, another 30-meter-long basin was built. The basin was built on dry land and launched in the water like a ship.

Right next to the swimming pool lay the factory’s football field. As its pitch had a foundation made of ceramic materials that ensured excellent drainage, it was famous for the turf’s resilience in rainy conditions.

Both pools were dismantled in the 1960s.

It was not until 1974 that a new swimming pool was set up in Jimbolia. It had a 50 m long and 2 m deep basin, changing cabins and two tennis courts, several table tennis options and a kiosk serving refreshments. The pool is supplied with thermal water.

Figure 2.7a: The Theiss Public Pool opened in 1925

Source: Sergiu Petru Dema Collection

Figure 2.7b: The House of Culture opened in 1925

Source: Sergiu Petru Dema Collection

Figure 2.7c: The Greek Orthodox church opened in 1942

Source: Sergiu Petru Dema Collection

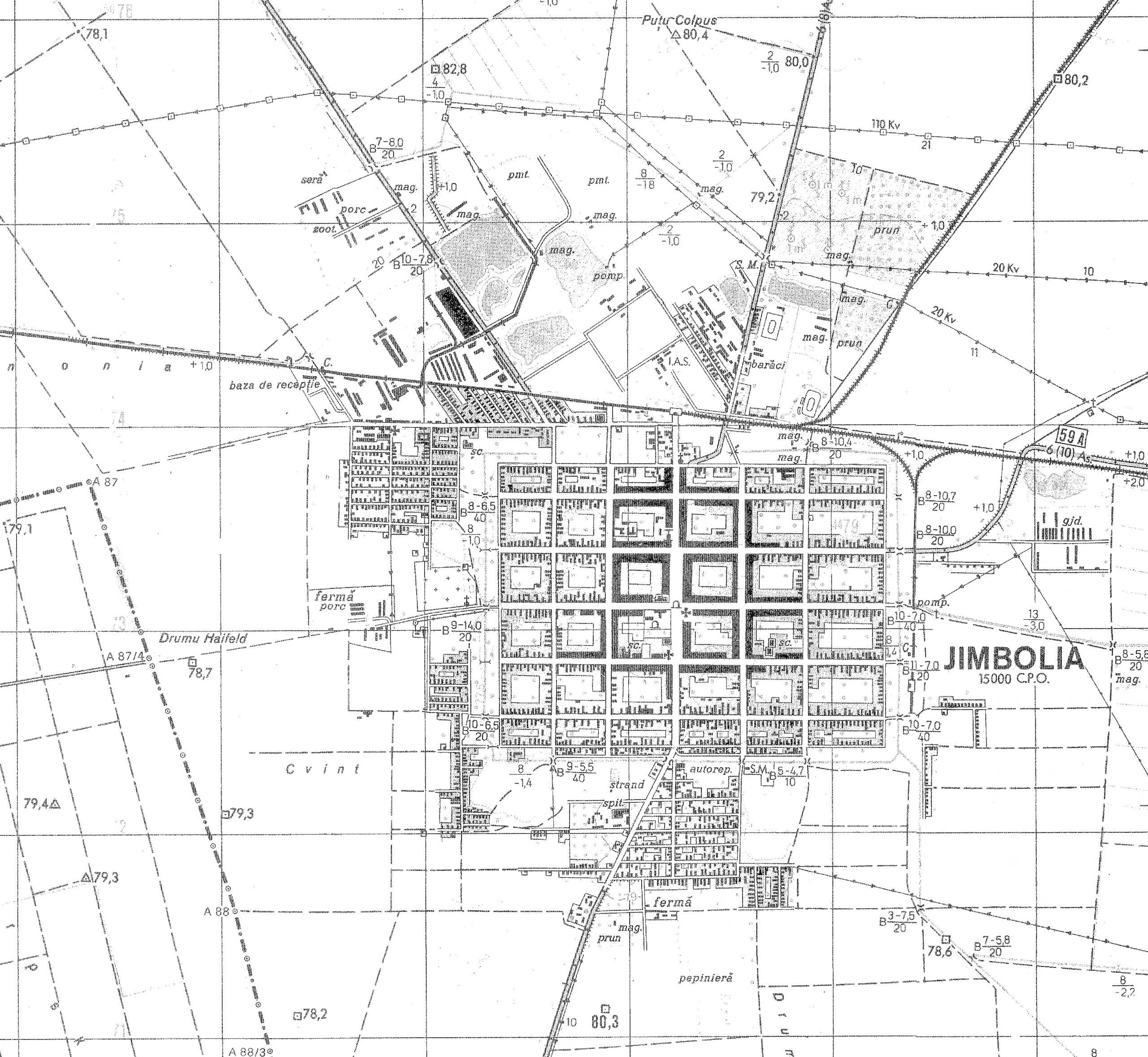

Later on, during the communist administration, some insertions of collective dwellings were made in the northern part of the settlement, between the train station and the first row of plots of the initial settlement. But the most impressive project of the period, with a significant impact on a territorial scale, is the systematization of the drainage canals’ network. Acting as a system relevant for both urban and non-urban areas, it ensures the drainage of both agricultural land as well as that of urban groundwater systems.

Figure 2.8: Jimbolia under the communist administration (second half of the 20th century)

National Archives (1970), Digital scans of the topographic surveys

One particularly interesting element is the drainage canal located on the settlement’s perimeter, between the original urban structure and the new extensions, which was created by joining the ring of kaules dug at the end of each street. One can thus observe the continuity between distinct historical stages and the way in which more recent periods have used the previous infrastructure to implement contemporary systems – the fundamental principles that characterize the heritage.

Finally, now, with the disappearance of the economic means that made it relevant on a larger scale, the settlement became a local socio-economic pole, providing jobs and services for hinterland communities. The following class (O1. M1.04 – Reinventing the grid: the thin line between relevance and oblivion. Case study: Jimbolia in the new economic context) further concentrates on detailing the present-day situation of the settlement, in relation to the major projects and investments carried out in recent years.

This chapter thus emphasizes the impact of historical periods (and the characteristic infrastructures developed during each of them). Further analyzed in GIS, this information creates the premises for the better understanding of their influence on the urban structure itself.

Chapter 3. Reshaping networks and borders: historical readings.

Teaching method: lecture – exemplification, case study

Duration: 60 min

The following chapter proposes a change of scale: from the particular case of Jimbolia to the territorial level. Within this framework one of the goals of this chapter is to emphasize the relevance of understanding the historical background related to the creation and to the interruption of territorial economical/political/cultural networks. This leads in the end to the ability to evaluate Jimbolia case study referencing the broader context of the region. A second goal of this chapter is to present students potential instruments of research and possible connections with other fields of research (in this case history based) such as social, political, economic sciences.

The structure of this chapter has as starting point the key moments of the urban transformation of Jimbolia. Therefore, along this chapter, a wider understanding of the triggers for growth at the regional level is displayed according to the decisive role of the political/economical context during the late 19th century until the fall of communism in the late 20th century.

The three main references for Jimbolia’s urban evolution were identified in the previous chapters as: the extension of the town structure determined by the development of the brick-tile industry; the relative stagnation of the urban evolution due to the interwar destiny of Jimbolia as border town; the transformation of the urban fabric in the last decades of the communist period. The method used along this chapter consists in displaying a series of narratives meant to depict the broader context for the three particular moments of Jimbolia’s urban evolution.

The first narrative is constructed around the Bohn-Muschong family business[4], considered relevant for the industrial development of the 19th century Jimbolia[5].The construction of Futok workers’ neighborhood as an extension of the gridded town of Jimbolia was an investment (1879) of the Bohn & Co ceramic tile industry, started in 1864 in Jimbolia. Bohn’s investment in Jimbolia was due to the gains of his previous investments started around 1850 in Sveti Hubert[6], his native town. Other investments followed and in 1877 he opened a brick factory Kikinda[7], around 1880 the factory in Lugoj was established and in 1890 Bohn opened another brick factory in Károlyliget. Kikinda and Lugoj were already places with a certain tradition in manufacturing brick and connected to the name of Jakob Muschong, who, in 1888 became the son-in-law of Stefan Bohn. And soon, the family business was run by the younger generation and the network extended in the territory, even after the split between Michael Bohn (son of Stefan) and Jakob Muschong (son-in-law of Stefan Bohn). Michael opened a factory in Békéscsaba and Jakob bought two more brick factories in Lugoj. The two brothers-in-law accumulated in time more brick factories for their two distinctive businesses: in Jimbolia (Bohn, 1903) Lipova (Bohn, year?), Feldioara – Brașov (Bohn, 1936-1937), Sântimbru-Alba (Muschong, 1912), near (not specified?) Budapest (Muschong, year ?) either to increase the production and to better cover the market in new areas, or to eliminate the competitors. Muschon, more business oriented, diversified his investments and bought (year?) a Mill in Lugoj and in 1907 became the owner of the spa resorts in Buziaș and opening a business oriented in the production and distribution of the local mineral water (Phöenix – Muschong).

Recent writings are indicating the importance of Bohn – Muschong family investments, especially focused on Jocob Muschong’s personality, referring to the brick factories network that he created as “a real «empire»”[8], based on the fame that he had in his times as the “the richest man in Banat (…) the founder of the largest brick and tile factories of the country”(Romania).[9]. As it is indicated in the current studies, the role of their technical innovations made their products reliable in the former Austro Hungarian Empire being still international after the First World War[10].

This perspective over the Bohn – Muschong industrial network gives the opportunity to add another frame to this level of discussion: the family business history. The interest in the history of family business dates especially from the late 20th century, in the same period when the interest in microhistory started in Italy. In the 1970s, and then in his later writings, Jürgen Kocka (social history) emphasized the relevance of the familial structures in the early industrialization in the German context[11]. Since then several authors focused their research on different case studies within Western and Central Eastern Europe. In more recent writings, the approach in the history family business tends to create comparative perspectives within a larger geo-political territory, concluding that even if there are different patterns of diffusion of the industrialization process in the European territory (for example), with different specific national factors, still family businesses represents a constant pattern in the industrial development[12]. A relatively recent publication displays in an atlas format the history of 100 hundred case studies of European family businesses in relation to the industrialization emphasizing in the conclusion of the book that the specific role of the family businesses was to create endurance through a conservative attitude (preservation of the business within the family) and through innovation (technical innovation and growth strategies) which created the stability of the industrialization process in the territory[13].

Issues and perspectives: First of all, it has to be mentioned that the main basin of case studies was, for the researchers, Western (and Central) Europe, the cradle of industrialization. And we can understand the less representation[14] of the (Central and) Eastern European case studies due to two factors: the territory was in a backward economical condition[15] and the post-war destiny of Eastern Europe cut completely all of the pre-existent independent economical structures as mechanisms and as research fields. This creates a specificity of the family business history in the context of Central Eastern Europe: from the point of view of the territorial and political reorganization after the first world war and from the point of view of the strategies of nationalization, industrialization and centralized economy, specific to the communist states. Secondly, a different perspective for the history readings can be opened, even if less addressed here, from the point of view of the family business in the brick industries and their role in the urban development during the late 19th century, especially at the periphery of the Dualist Empire. Such a perspective is able to enrich the great narrative of the foundation of the brick industry in central Europe, at the beginning of the 19th century, tight to the name of Alois Miesbach (along with his successor, Heinrich Drasche) of whose company, firstly established in Inzendorf, next to Vienna and latter expanded (by the end of the century) to Croatia, Slovakia and Bohemia[16]. Bohn – Muschong family interest in technical innovation – Grand Prix at the specific industrial exhibitions in Timișoara (1895), Arad (1897), Budapest (1898) and Paris (1900)[17] – is to be added to another family business oriented toward innovation: the Zsolnay family, whose products are very much related to the nationalist movement in modern architecture, at the beginning of the 20th century[18].

The second narrative details aspects relevant to the interwar political context, when the Banat region was divided between Romania and the Serbian Kingdom. During the interwar period Jimbolia was successively a town located at the periphery first of the Serbian Kingdom, and after 1924 of the Romanian state, both – as most of the interwar states – under the auspices of nation centered political economy. The relevance of introducing this perspective is due to the effects that national centered economies had in the region. In the early 1930s’ Sir Arthur Salter wrote an article published by the Council of Foreign Nations and entitled “The Future of Economic Nationalism” in which he was exposing the potential of the national economies for the less developed countries and also the threats that closed economies could have if the already established networks in the territory were cut. In 2000, an article entitled “The Failure of Economic Nationalism: Central Eastern Europe before World War II ” gives a clear response regarding the several dysfunctions that the centralized economic policies had, emphasizing their negative impact in the territory[19]. Specific to the national economies was: the issue of state policies for cutting the imports and controlling the external economical networks (imports and exports) aiming self development and independence; the central role of the protectionist policies for the domestic investors; state investments replacing the private enterprises[20].

The myth of the great industrialization and economic growth of interwar Romania – as an imaginary resistance during the communist period and in the early 1990’s – is more and more questioned in recent studies. Bogdan Murgescu is shaping in his main work, the characteristics of the Romanian case of national economy, based on the liberal party formula, “through ourselves”, following several generic patterns: the appropriation of the foreign investments by the state; augmentation of the exportation taxes and restriction on exports and relaxed in some respects by the policies of the “open gates” promoted by the National Peasant Party in the late 1920 and early 1930[21].

Reflexions of the overall political – economical context can be decrypt also through Bohn – Muschong case having as starting point a local legend that stipulates the fact that after the Unification of Romania, Muschong was exposed to a real harassment by the central state The legend speculated further that being accused of fraud, he found his death due to a heart attack. Without intending to unveil the truth on this particular matter, we expose further two extracts of the primary sources dating from the interwar period. The first one is addressing an issue of a national oriented publication (Revista Insitutului Social Banat-Crișana, aprilie-iulie, 1936) which displayed under the bolded title: Romanian Investments registered in Timișoara: 313 businesses of which only 14 have Romanian origin, together with the comment: “An aspect of the economical life at the western border of Romania. The worrisome situation regarding Romanians towards industry, occupation, trade and agrarian ownership“ (among the foreign investments both Muschong investment in Buziaș and Bohn’s brick factory in Jimbolia were listed). A second source refers to an article published in the Monitor of Bucharest’s Municipality (1943) that was announcing the opening of a process: the Romanian State against Muschong for using of the railway connecting the main station of Buziaș to the Spa resorts, which, since 1919 passed from Muschong’s possession into the Romanian State possession[22].

Issues and perspectives: The imaginary of the glorious interwar period for Central Eastern Europe has to be understood as a period of more complexity and it involves specific transnational comparative studies in order to display the real radiography of the deep cuts in the economical networks of the region.

The third narrative details the specific context of the last decades of the communist period which marked the evolution of the Romanian urban landscape, referencing the urban interventions made in Jimbolia after 1974. After the period of a tolerable climate in 1960-1970’s communist Romania, beginning with the mid seventies Romanian entered the last phase of the national communism, marked by a more centralized and politicized system. Such context had been reflected in a series of inefficient economic decisions[23] that indirectly affected the urban development, but more directly, in the specific legislation related to the urban development (systematization). A few years after the last communist territorial – administrative reorganization (1968) based on the communist economical pattern of industrialization, the centralized institution with direct involvement in coordinating the local administration was once again (1973) reorganized under the name of Committee for Local Administrative issues[24]. Starting with this moment the activity in the field of systematization began to be more centralized and the production of projects and interventions were more intense. A specific legislation addressed to dwelling, town and circulation systematization in the same period (1973-1975). Without detailing the particular aspects, it must be emphasized that the most relevant aspects of the particular interest of the political regime in modernizing the town structure and creating urbanity. Due to this objective, beside the densification of the mass housing areas, interventions of urban renovation transformed especially the centres of several towns in Romania, run in a more accelerated and brutal process (expropriations and demolishing) than the previous decades[25].

Also a particularity of this period was the interest in the transformation of the small scale towns and settlements. Such a perspective urged an artificial conversion of several rural settlements and small towns to un urban status.[4] The town status assigned to a locality was mirrored in the urban interventions and in the creation of a civic centre of the locality. For example, in Timiș county, until 1976, Timișoara and Lugoj were the main cities and Buziaș, Jimbolia, Deta and Sânicolau Mare had the status of towns. For the period 1976-1985 seven other settlements were proposed to change their status to towns: Recaș, Lovrin, Făget, Nădrag, Gătaia, Ciacova, Peciu Nou. Objectively, neither the economical perspectives, nor the features (rather rural in terms of structure, built fabric and density) of these settlements previously cited could rationally predict the insertion of an urban fabric. In the mid 1970s the small industrial town of Bocșa (Bocșa Română, Caraș Severin) was supposed to extend its industry and according to that a new civic centre was planned together with an area of collective housing. The investments limited to the construction of the housing blocs, transforming the rural aspect of the settlement[26]. In the same period, in more other small towns or rural settlements the pair – pattern of housing blocs and civic centre was introduced. Although official documents and predictions underlined the importance of preserving the local characteristics, the new insertions created an obvious discrepancy with the existent context, which differed in scale and density.

Issues and perspectives: The series of interventions previously described may be understood as the product of a centralized power which marked the territory through a specific network of interventions, now recognizable as a recurring pattern (more brutally visible in the small-scale localities) of the communist Romanian territory.

Chapter 4. Impact on real-life communities: identification of the main triggers for growth and interpretation of the impact they have on the urban structure

Teaching method: workshop – utilizing specific instruments (a GIS-based application)

Duration: 75 min

The expansion, as well as the alteration of the grid in relation to external and internal stimuli, are further analyzed within the workshop component of this course, through the overlapping of historical plans in a GIS-based application and the identification of the main triggers for growth.

This chapter therefore concentrates on understanding the interaction among the economy, transportation, health and human services, as well as land-use regulation, helping students to develop the ability to identify the main triggers for growth within a settlement, as well as to interpret the impact they have on the urban structure, through the comparative analysis of historical plans.

Summarizing the information from previous chapters, a new model of interpretation is generated and applied to Jimbolia’s case. Thus, the determinants of economic growth in the contemporary period are identified (such as access to infrastructure, favorable position in the network of localities, human capital, or infrastructure that allows local connection between a polarizing urban locality and settlements in the immediate vicinity). At the same time, they are interpreted in relation to the case study of Jimbolia and the possibilities it presents.

Using a GIS-based application, students will overlap maps of the town of Jimbolia from distinct periods of time, in order to identify:

- alterations of the existing urban structure / new expansions within the surrounding territory;

- the main objectives developed in and around the town of Jimbolia (such as infrastructure works, industrial facilities, workers’ colonies, manors for the bourgeoisie, etc.);

- the main connection routes (roads, railroads, navigable routes).

The exercise begins with setting the work environment:

- the visual support for the analysis: the present day map of the town of Jimbolia;

- the historical maps that are to be overlapped: the First Habsburg Topographical Survey of Jimbolia / the Second Habsburg Topographical Survey of Jimbolia / Jimbolia in the early 20th century / Jimbolia following the First World War / Jimbolia under communist administration – second half of the 20th century;

- the specific layers for every analyzed aspect:

- elements of urban structure – streets, plots, buildings;

- functional areas – residential (different types), commercial, public facilities, industrial, infrastructure;

- connection routes (roads / railroads / navigable routes);

- other technical works (drainage canals).

The exercise continues with direct observations regarding the triggers for growth, that determine either the densification of the existing built tissue or the expansion of the urban form, in relation to the realities of the town of Jimbolia. Students are encouraged to analyze the different stimuli that determine growth and transformation within the settlement, as well as the impact that they have upon the existing urban structure. At the same time, the exercise focuses on understanding the interaction among the economy, transportation, health and human services, as well as land-use regulation.

[1] In this respect, see also Angel, S.; Sheppard, St. C. & Civco, D. L. (2005). The Dynamics of Global Urban Expansion. Transport and Urban Development Department. The World Bank [2] In this respect, see also Pelczynski, J. & Tomkowicz, B. (2019). Densification of cities as a method of sustainable development, in IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Sciences. 362, 012106 [3] In this respect, see also Radoslav, R.; Bădescu, Ș.; Branea, A.M.; Danciu, M. & Găman, M.S. (2012). Sistemul urban Timișoara în epoca modernă, in Urbanismul Serie nouă, Nr. 12-13 [4] All the information on the history of the Bohn-Muschong industrial investments in the region, presented here synthesizes several secondary sources of different types: materials written by local monographers, encyclopedias, industrial heritage related works and others. In this respect, we cite: Bodó Barna (coord.), Ghid cronologic pentru orașele Bănățene (Timișoara, Lugoj, Reșița, Caransebeș, Pancevo, Kikinda, Zrenjanin, Vrsac, Ed. Fundația Diaspora Timișoara, Timișoara, 2007 and Bodó Barna (coord.), Ghid cronologic al orașelor Anina, Băile Herculane, Bocșa, Buziaș, Ciacova, Deta, Făget, Gătaia, Jimbolia, Moldova Nouă, Oravița, Oțelu Roșu, Recaș, Sânnicolau Mare - România și Alibunar, Biserica Albă, Čoka, Kovin, Novi Bečej, Nova Crnja, Novi Kneževac, Sečanj, Žitište - Serbia, Ed.?, Timișoara, 2009; Jucu, Ioan Sebastian, Pavel Sorin Costel, “Identifying Industrial Heritage of Small and Medium-Sized Towns: Two Samples from Timiș County” in Analele Asociației Profesionale a Geografilor din România, Ed. Universitară, Vol. 9, 2018; Jucu, Ioan Sebastian, ”Selective issues on Buziaș touristic Resort of Romania between emblematic tourism economies and post-communist dereliction” in GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, Vol. 18, Nr. 2, 2016; Volker Wollmann, Patrimoniul preindustrial și industrial în România, Vol. II, Ed. Honterus, Sibiu, 2011, pp. 201-233. Nevertheless, none of the materials is focused on exposing the entire industrial network of the Bohn-Muschong family business completely documented. Inaccuracies have been identified in relation to the detailed history (years/places/facts etc.) and they are reflecting the difficulties in working with the transnational primary sources. In this respect we consider useful the proposal of a specific teaching module with application focused on the use of primary sources related to transnational archive research of the area. [5] The specific history of Bohn-Muschong industrial investment in Jimbolia was presented during the Summer-school in Jimbolia, organized as part of the Triplex Confinium Project. Video materials were posted on the site’s blog: https://triplex-confinium.eu/blog. We consider such materials as useful plug-ins on local history for courses dedicated to the cultural heritage of Banat region. [6] As they are indicated on the Second Military Survey of the Habsburg Empire (1819-1869)(SMSHE) the three colonial settlements, established in 18th century, were: Szent Hubert (Sveti Hubert, Sankt Hubert), Charleville (Károlyliget) and Seultour (Soltur, Szoltur, Szeultorn). The three colonies formed later the village, known since 1948 as Banatsko Veliko Selo. [7] Kikinda (Chichinda) or Gross Kikinda as indicated on the SMSHE, is a 18th century colonial settlement, with consistent similarities to Jimbolia. [8] Volker Wollmann, op. cit. [9] As it was mentioned in his obituary in 1923, Vestul României, Nr. 63, 1923. [10] The patterns created by Bohn and Muschong were referenced as “types”, along with a few other patterns industrialized by different producers, for brick and tile construction materials (Victor Asquini, Indicator tehnic în construcții, Ed. Cartea Românească, București, 1945). [11] Jürgen Kocka, “Familie, unternehmer und kapitalismus. An beispielen aus der frühen Deutschen industrialiserung” in Zeitschrift für Unternehmensgeschichte / Journal of Business History, 1979, Nr. 3, pp. 99-135. [12] In this respect see: Andrea Colli, The History of Family Business, 1850-2000, Cambridge University Press, 2003. [13] Josep, Tàpies, Elena San Román, Águeda Gil López, 100 Families that Changed the World. Family Business and Industrialization, Ed. Fundacion Jesus Serra, Barcelona, 2016. [14] Petr, Popelka, Hopkinson, Christopher, “Business Strategies and Adaptation Mechanisms in Family Businesses during the Era of the Industrial Revolution: The Example of the Klein Family from Moravia”, in The Hungarian Historical Review, 2015, Vol. 4, pp. 805-833, see: pp. 807-808. [15] Several seminal writings are analyzing the diffusion of the industrial – economy towards the periphery of the Habsburg Empire and the uprising industrialisation, following the Compromise (the formation of Austro-Hungarian Empire). We cite here a very recent work related to the industrialization of Vojvodina region, therefore in relation with the main case study of the course: Anca Draganić, ”Conservation approach to the industrial heritage of Vojvodina'' in Facta Universitatis. Architecture and Civil Engineering. Vol. 17, nr. 4, 2019, pp.377-386. [16] Paul Mitchell, “Bricks in the central part of Austria-Hungary. Key artefacts in historical archeology” in Historiche Archaologie, 2009. [17] Volker Wollmann, op. Cit., p. 224. [18] In this respect, see: Éva Csenkey and Ágota Steinert (eds), Hungarian Ceramics from the Zsolnay Manufactory, 1853-2001, Yale University Press, London, 2002; Zoltán Kaposi, “Entrepreneurs, Enterprises and Innovation in Pécs (1850–1914)“: doi: 10.15170/SESHST-02-02. [19] Ivan T. Berend, “The failure of Economic Nationalism: Central and eastern Europe before World War II” in Revue économique, Vol 51, Nr. 2, 2000, pp. 315-322. [20] Helga, Schutz, Eduard Kubů (eds.), History and Culture of Economic Nationalism in East Central Europe, Berlin, 2006. [21] Bogdan Murgescu, România și Europa. Acumularea decalajelor economice (1500-2012), Ed. Polirom, București, 2010. [22] Gazeta Municipală, București, 587, 1943, p. 1. [23] Bogdan Murgescu, op. cit. , pp. 338-339. [24] Comitetul de Stat pentru Problemele Consiliilor Populare. [25] Irina Tulbure, „Orașul și centrul său dintr-o perspectivă a istoriei recente” în Ilinca Constantinescu (Păun) ed., Shrinking cities in Romania. Orașe românești în declin, Ed. Dom, Berlin, 2019. [26] The settlement was established as an industrial town integrating three different ethnic settlements, dispersed in territory and administratively united in 1961: Vasiova, German Bocșa and Romanian Bocșa.

References

- Angel, S.; Sheppard, St. C. & Civco, D. L. (2005). The Dynamics of Global Urban Expansion. Transport and Urban Development Department. The World Bank, available at: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.309.2715&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Pelczynski, J. & Tomkowicz, B. (2019). Densification of cities as a method of sustainable development, in IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Sciences. 362, 012106. available at: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1755-1315/362/1/012106/pdf

- Sanchez-Zamora, P.; Gallardo-Cobos, R.; Cena Delgado, F. The Notion of Resilience in the Analysis of the Rural Territorial Dynamics: An Approach to the Concept through a Territorial Approach, in CUADERNOS DE DESARROLLO RURAL, available at: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/full-record/WOS:000384838300004

- Zhang, MJ: Peng, C; Shu, JF; Lin, YZ. (2022). Territorial Resilience of Metropolitan Regions: A Conceptual Framework, Recognition Methodologies and Planning Response-A Case Study of Wuhan Metropolitan Region, in INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ENVIRONMENTAL RESEARCH AND PUBLIC HEALTH, available at: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/full-record/WOS:000771939000001

- Goncalves, C. PERSPECTIVES ON TERRITORIAL RESILIENCE: FLEXIBLE RESISTANCE, SYSTEMIC INTERDEPENDENCE, EVOLUTIONARY ADAPTABILITY, in GEOGRAPHIA-UFF, Vol. 20, Issue 43

- Gheorghiu, T.O. (2019). The rural habitat and the Habsburg administration, in Neumann, V. The Banat of Timișoara: A European Melting Pot. London: Scala Arts Publishers Inc.

- Tulbure, Irina, „Orașul și centrul său dintr-o perspectivă a istoriei recente” în Ilinca Constantinescu (Păun) ed., Shrinking cities in Romania. Orașe românești în declin, Ed. Dom, Berlin, 2019.

- Gheorghiu, T.O. (2018) Mici orașe / mari sate din sud-vestul României. Monografii urbanistice. Bucharest: Simetria

- Jucu, Ioan Sebastian, Pavel Sorin Costel, “Identifying Industrial Heritage of Small and Medium-Sized Towns: Two Samples from Timiș County” in Analele Asociației Profesionale a Geografilor din România, Ed. Universitară, Vol. 9, 2018

- Jucu, Ioan Sebastian, ”Selective issues on Buziaș touristic Resort of Romania between emblematic tourism economies and post-communist dereliction” in GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, Vol. 18, Nr. 2, 2016

- Tàpies, Josep, San Román, Elena, Gil López, Águeda, 100 Families that Changed the World. Family Business and Industrialization, Ed. Fundacion Jesus Serra, Barcelona, 2016

- Popelka, Petr, Hopkinson, Christopher, “Business Strategies and Adaptation Mechanisms in Family Businesses during the Era of the Industrial Revolution: The Example of the Klein Family from Moravia”, in The Hungarian Historical Review, 2015, Vol. 4, pp. 805-833, see: pp. 807-808

- Radoslav R., Bădescu, S., Danciu, M.I. (2014). Evoluția parcelării în relație cu extinderea aglomerării urbane Timișoara, in Urbanismul Serie nouă, Nr. 16-17

- Radoslav, R.; Bădescu, Ș.; Branea, A.M.; Danciu, M. & Găman, M.S. (2012). Sistemul urban Timișoara în epoca modernă, in Urbanismul Serie nouă, Nr. 12-13

- Gheorghiu, T.O. (2011). Sistematizarea Rurală în Banatul Secolelor XVIII-XIX, in Urbanismul. Serie Nouă, Nr. 7-8

- Volker Wollmann, Patrimoniul preindustrial și industrial în România, Vol. II, Ed. Honterus, Sibiu, 2011, pp. 201-233

- Anca Draganić, ”Conservation approach to the industrial heritage of Vojvodina” in Facta Universitatis. Architecture and Civil Engineering. Vol. 17, nr. 4, 2019, pp.377-386

- Bogdan Murgescu, România și Europa. Acumularea decalajelor economice (1500-2012), Ed. Polirom, București, 2010.

- Mitchell, Paul , “Bricks in the central part of Austria-Hungary. Key artefacts in historical archeology” in Historiche Archaologie, 2009.

- Bodó Barna (coord.), Ghid cronologic al orașelor Anina, Băile Herculane, Bocșa, Buziaș, Ciacova, Deta, Făget, Gătaia, Jimbolia, Moldova Nouă, Oravița, Oțelu Roșu, Recaș, Sânicolau Mare – România și Alibunar, Biserica Albă, Čoka, Kovin, Novi Bečej, Nova Crnja, Novi Kneževac, Sečanj, Žitište – Serbia, Ed.?, Timișoara, 2009

- Bodó Barna (coord.), Ghid cronologic pentru orașele Bănățene (Timișoara, Lugoj, Reșița, Caransebeș, Pancevo, Kikinda, Zrenjanin, Vrsac, Ed. Fundația Diaspora Timișoara, Timișoara, 2007

- Ianoș, Ioan, Dinamica urbană. Aplicații la orașul și sistemul urban românesc, Ed. Tehnică, București, 2004

- Colli, Andrea, The History of Family Business, 1850-2000, Cambridge University Press, 2003

- Csenkey, Éva and Steinert, Ágota (eds), Hungarian Ceramics from the Zsolnay Manufactory, 1853-2001, Yale University Press, London, 2002; Zoltán Kaposi, “Entrepreneurs, Enterprises and Innovation in Pécs (1850–1914)“

- Berend, Ivan T., “The failure of Economic Nationalism: Central and eastern Europe before World War II” in Revue économique, Vol 51, Nr. 2, 2000, pp. 315-322

Other Instructors

Ioan ANDREESCU

Professor

Cristian BLIDARIU

Associate Professor

Oana SIMIONESCU

Teaching Assistant

Ana BRANEA

Associate Professor

Mihai DANCIU

Teaching Assistant

Bogdan DEMETRESCU

Associate Professor

Bogdan ISOPESCU

Teaching Assistant

Ștefana BĂDESCU

Assistant Lecturer

Dan Răzvan DINU

Assistant Lecturer

Syllabus

The aim of this class is to facilitate the objective understanding of a territory, through the analysis of the physical components that determine its structure. In the case of colonial settlements, these refer to the grid - the urban pattern which allows settlers to create easily expandable structures that can grow in any direction and occupy the land following a clear set of rules. This course therefore concentrates on explaining the subordinating powers of the grid in relation to the surrounding territory, while also demonstrating its ability to accommodate growth and transformation within the fixed confines of strong physical borders. These principles are further analyzed in relation to the urban development of Jimbolia throughout the 19th and 20th century. Established by colonists brought here by the Habsburgs at the end of the 18th century, the town of Jimbolia gradually expanded throughout the 19th century, with the urban form following the shape of the large agricultural plots surrounding the settlement; at the same time, given the strong physical borders created around Jimbolia (in the form of large clay pits, which enclose the built tissue), one can also witness the growth within the grid - the continuous adaptation and transformation of the urban structure in order to accommodate and absorb the economical, infrastructural and social changes. The expansion, as well as the alteration of the grid in relation to external and internal stimuli, are further analyzed within the ‘workshop’ component of the second course, through the overlapping of historical plans in a GIS-based application and the identification of the main triggers for growth.

O1.M1 UNDERSTANDING THE TERRITORY AS A SYSTEM

O1.M1.03 Transformation and growth within the strict confines of the grid: economy, infrastructure and society - Case study: the urban development of Jimbolia throughout the 19th & 20th centuries

Type of format

Lecture & Workshop

Duration

135 min lecture (theoretical notions) 15 min break 75 min workshop (case study)

Possible connections (with other schools / presented topics)

UAUIM O1. M1.01 Grids, Formal tools for understanding and manipulating space O1. M1.05 Borders- theoretical research framework O1. M2. 03 Process vs Object. Working with post industrial communities SUSKO O1. M2.02 Introduction to GIS story maps BME O1. M1.06 HISTORY DRAWN IN THE LANDSCAPE O1. M3.02.01. Working with the cultural landscape O1. M3.02.02. Working with the (invisible) built heritage UBB O1 M2. 04. Speaking with communities

Main purpose & objectives

The main purpose of this class is to help students understand and recognize the various morphological features of colonial settlements, as well as the way in which these can evolve and adapt (as a result of the interaction between economy, transportation, health and human services, as well as land-use regulation). In addition, the class introduces objective methods by which students can understand the prospective evolution of a territory, helping them to acquire design skills in relation to a context that is stagnant, declining or increasing. Especially relevant for major infrastructure projects, single public objectives and repetitive ones (such as national / cross-border facilities and connections), this class offers the possibility of a realistic approach, adapted to the context and economic realities of a particular site. This course therefore concentrates on the following objectives: introducing students to the different growth patterns specific for colonial settlements, be it through expansion within the surrounding territory or through the adaptation of the existing urban structure; analyzing the different stimuli that determine growth and transformation within urban settlements, as well as the impact that they have upon the existing urban structure; understanding the interaction among the economy, transportation, health and human services, as well as land-use regulation. The goal of the third chapter is to emphasize the relevance of understanding the historical background related to the creation and to the interruption of territorial economical/political/cultural networks and to evaluate a particular case study referencing the broader context of the region. A second goal of this chapter is to present students potential instruments of research and possible connections with other fields of research.

Skills acquired

Detailed theoretical knowledge regarding the growth patterns of colonial settlements, be it through expansion within the surrounding territory or through the adaptation of the existing urban structure Deep understanding of the factors that generate growth and transformation within an urban structure The ability to identify the main triggers for growth within a settlement, as well as to interpret the impact they have on the urban structure, through the comparative analysis of historical plans The ability to find the wright anchor points in order to address specific other fields of research, connected to the urban and architectural evolution (history, social - sciences, politics, economy) in order to be able further to decide the scale of analysis, the recurrency of a phenomena, the singularity of a case study, its role in a potential territorial network.

Contents and teaching methods

1. Transformation and growth within the strict confines of the grid: expansion within the surrounding territory vs. adaptation of the existing urban structure Teaching method: lecture - theoretical approach 2. Triggers for growth: the close relationship between economy, society, infrastructure and the urban structure in the case of Jimbolia Teaching method: lecture - exemplification, case study 3. Reshaping networks and borders: historical readings Teaching method: lecture - exemplification, case study 4. Impact on real-life communities: identification of the main triggers for growth and interpretation of the impact they have on the urban structure Teaching method: workshop - utilizing specific instruments (a GIS-based application)

Reviews

Lorem Ipsn gravida nibh vel velit auctor aliquet. Aenean sollicitudin, lorem quis bibendum auci elit consequat ipsutis sem nibh id elit. Duis sed odio sit amet nibh vulputate cursus a sit amet mauris. Morbi accumsan ipsum velit. Nam nec tellus a odio tincidunt auctor a ornare odio. Sed non mauris vitae erat consequat auctor eu in elit.

Members

Lorem Ipsn gravida nibh vel velit auctor aliquet. Aenean sollicitudin, lorem quis bibendum auci elit consequat ipsutis sem nibh id elit. Duis sed odio sit amet nibh vulputate cursus a sit amet mauris. Morbi accumsan ipsum velit. Nam nec tellus a odio tincidunt auctor a ornare odio. Sed non mauris vitae erat consequat auctor eu in elit.