O1.M1.02. The power of the grid: subordination and regularization in colonial territorial planning – Case study: the historical region of Banat under the Habsburg rule

Free

About this course

Chapter 1. The power of the grid: a short theoretical introduction

Teaching method: lecture – theoretical approach

Duration: 15 min

The aim of this class is to facilitate the objective understanding of a territory, through the analysis of the physical components that determine its structure. In the case of colonial settlements, these refer to the grid – the almighty instrument, which allows settlers to create easily controllable and recognisable structures in a foreign land.

The grid – understood as both a generator of urban shape and a socio-economic analysis tool – is one of the most powerful and recognizable urban instruments in the history of mankind. The objective approach that it generates, as well as its unmistakable physical features, transform this instrument into one of the most resilient of its kind, able to withstand hundreds of years worth of changes.

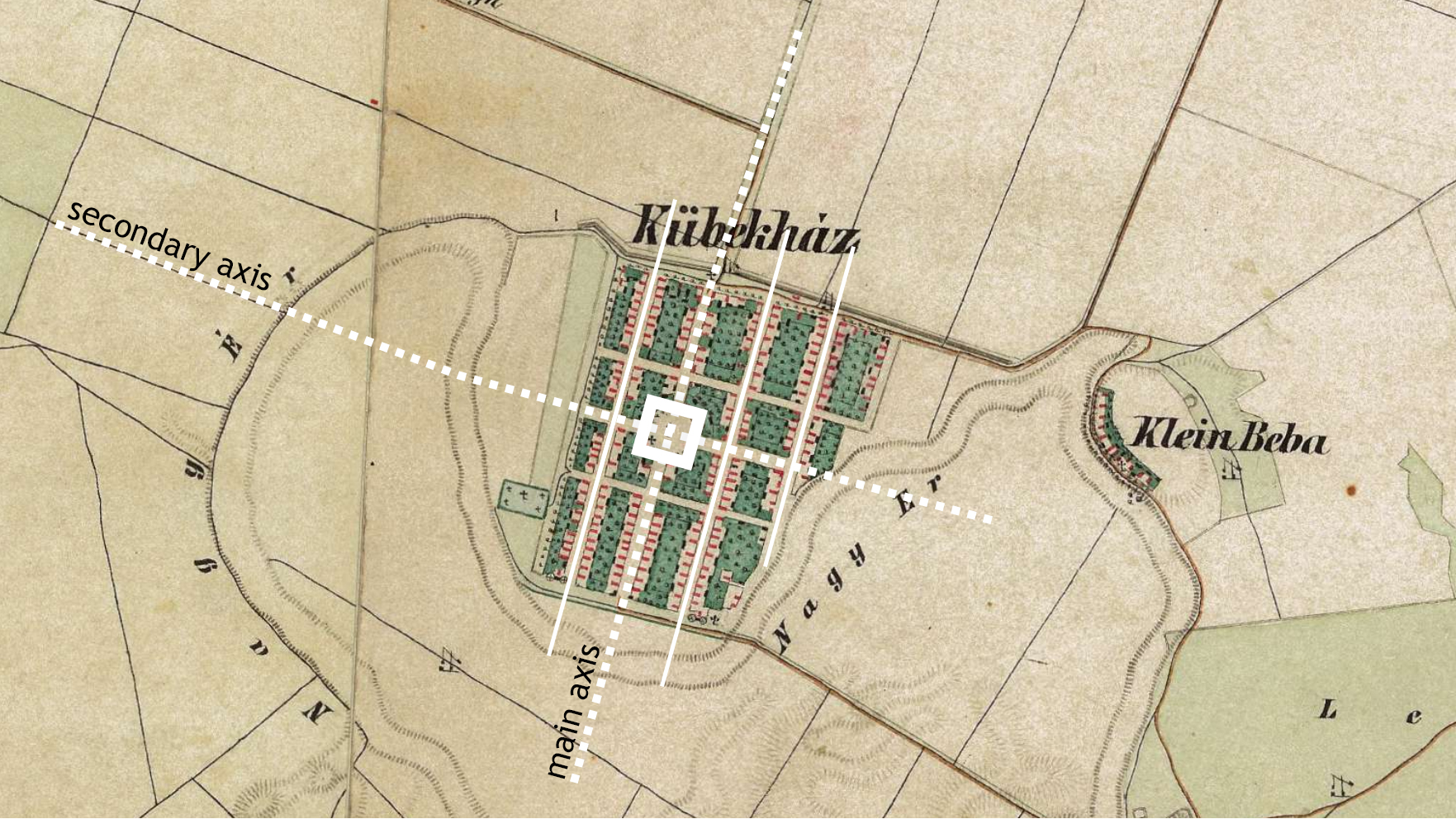

Figure 1.1 : The grid – axiality, centrality, repetition (schematic representation) represented on the example of Kubekhaza – currently Hungary

Second Habsburg Topographic Survey / Zweite oder Franziszeische Landesaufnahme (1806-1869), retrieved from mapire.eu

Figure 1.2 : The border – permeability vs. separation (schematic representation on the Jarkovac settlement – currently Serbia)

Present day satellite view, retrieved from mapire.eu on Google Earth background

Chapter 2. Colonial territorial planning under the Habsburg rule: theoretical principles of urban development

Teaching method: lecture – exemplification, case study

Duration: 30 min

The main purpose of this chapter is to help students understand and recognize the various morphological features of colonial settlements developed under the Hapsburg rule, as well as the way in which these can evolve and adapt (as a result of the interaction between economy, transportation, health and human services, as well as land-use regulation).

This chapter therefore concentrates on introducing students to a plethora of theoretical notions, regarding colonial territorial planning and the grid-like urban structures that they usually adopt – thus offering a profound understanding of colonial settlements developed under the Habsburg rule and the utilization of the grid in order to regulate and subordinate a newly-conquered territory.

Regardless of the historical period or the geographical area in which they emerge, colonial settlements, developed throughout the world, distinguish themselves from other rural and urban structures through both purpose and form.

Understood as villages and towns developed at the command of foreign rulers within newly conquered or occupied lands, colonial settlements’ sheer purpose is that of exploiting the recently gained resources, while also asserting the domination of the new ruling power within the territory.

To this end, colonial settlements utilize a particularly valuable resource – the profile of their inhabitants. As foreigners, brought here from distant lands, the settlers tend to stick together, distancing themselves from the existing population and maintaining their traditions, thus preserving a strong communitary identity and creating a distinctive impression among the locals. At the same time, being bestowed with certain privileges, settlers follow the rules imposed on them by the ruling power and accomplish the tasks they were given in exchange for said privileges.

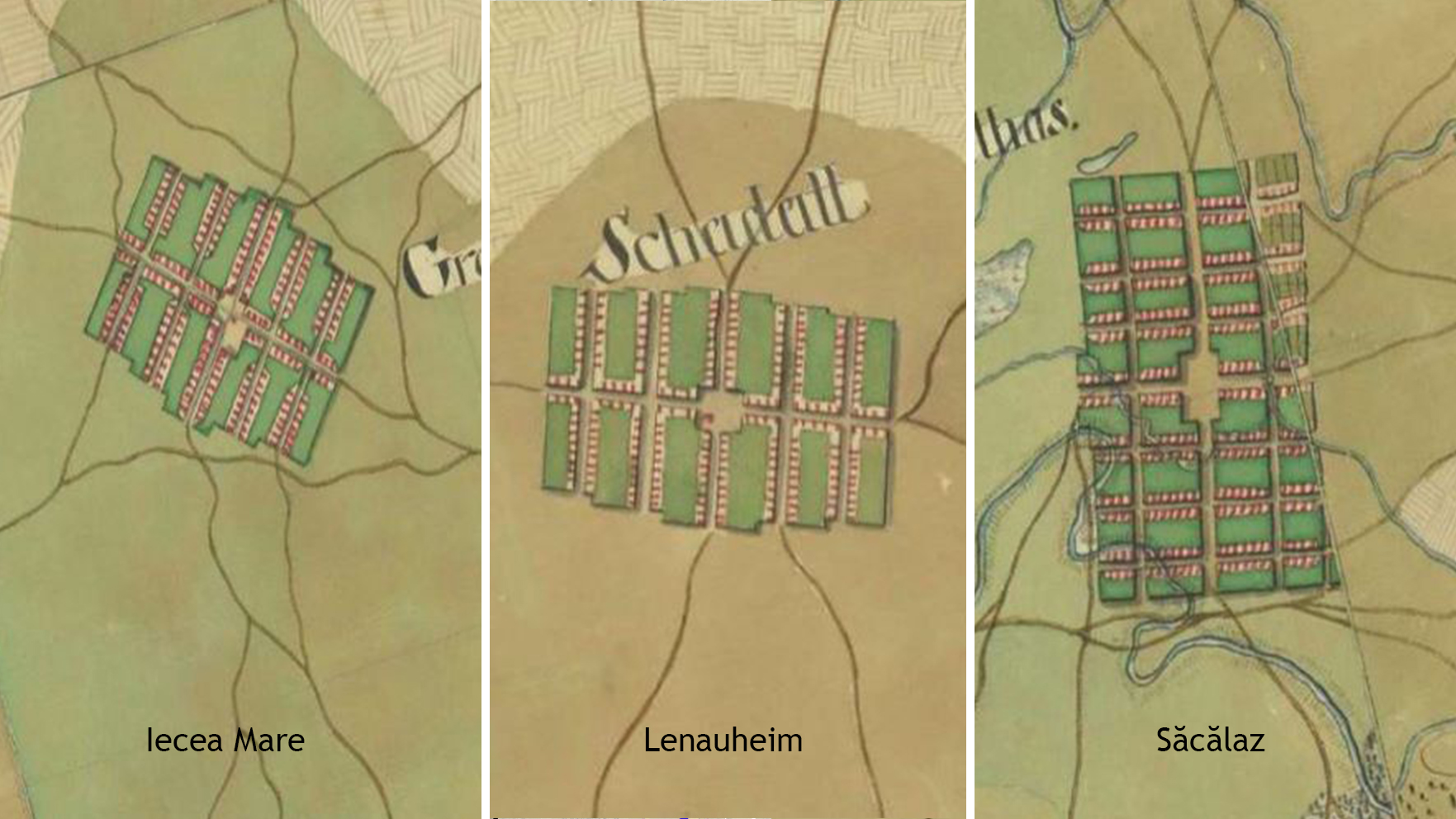

The 18th century colonization of the Banat was not an easy endeavor, and required a huge planning effort, in building its infrastructure, in moving in people from distant lands, in establishing some sense of order and control. Early settlers were decimated by the many diseases spewing from the marshy lands, just as new towns and villages were gradually being built. In the space of 50 years after the Habsburg reconquista, under the supervision of imperial council administrator Wilhem von Hildebrandt, as old villages like Comloșu Mare, were being reorganized along gridded layouts, new pre-planned settlements started dotting the Banat plains. These were built at regular intervals, alog existing or new roads, exploiting the features of the land, ready to receive the much needed labor force that was required to start the industrial and agricultural revolution in the new imperial Banat region. Oftentimes, villages were built in advance, before settlers even arrived. The urban layout respected the strictest efficiency rules. Rammed earth houses, built according to standardized projects, lined the spacious streets. To their backs, each benefited from a substantial plot of agricultural land. This was used by the settlers to their own benefit. The village was surrounded by an area of commons made up mostly by grazing grounds, used by the entire community. Outside it, the agricultural land of each village was again, equally parceled in agricultural plots, attributed to each family.

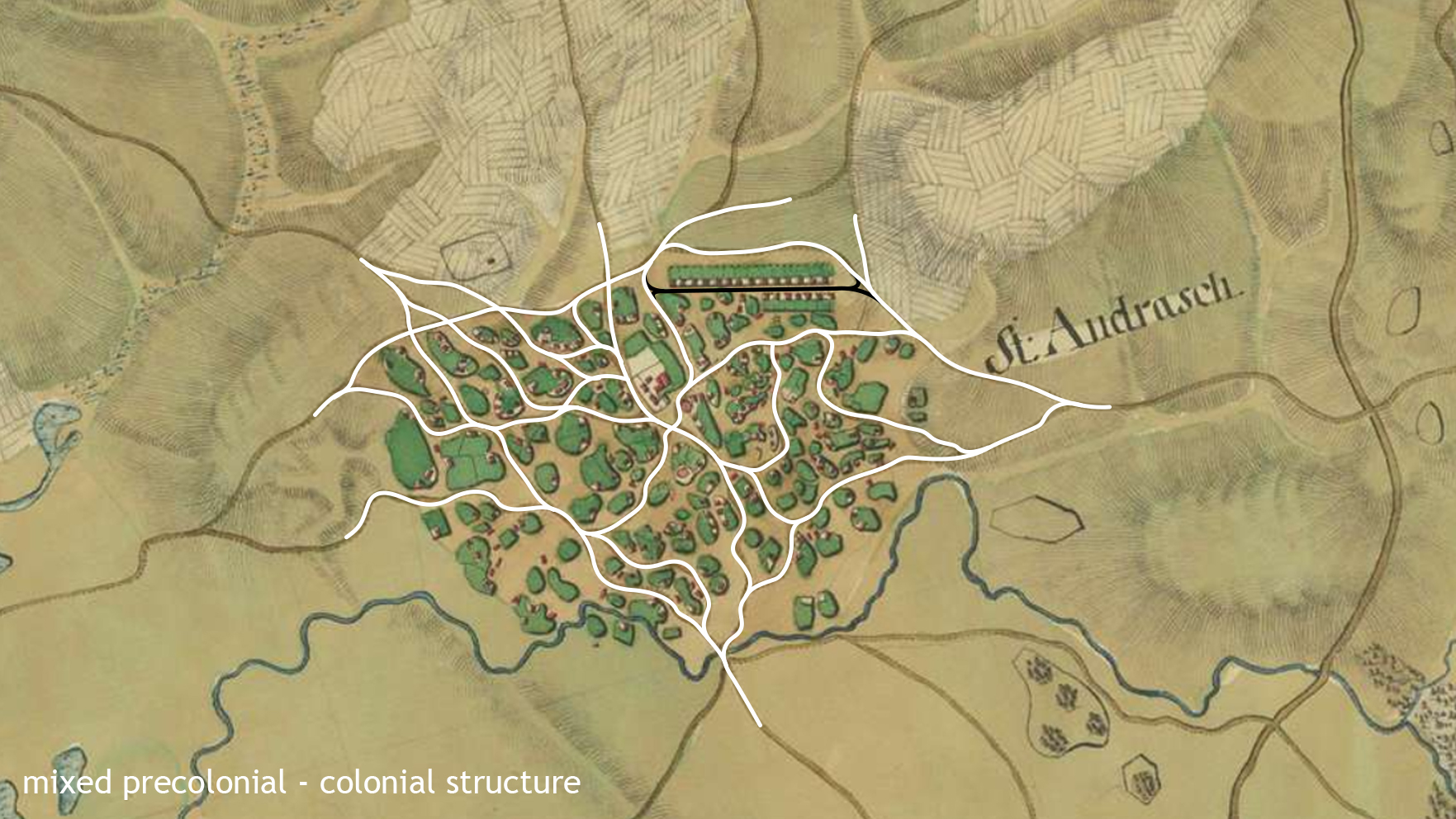

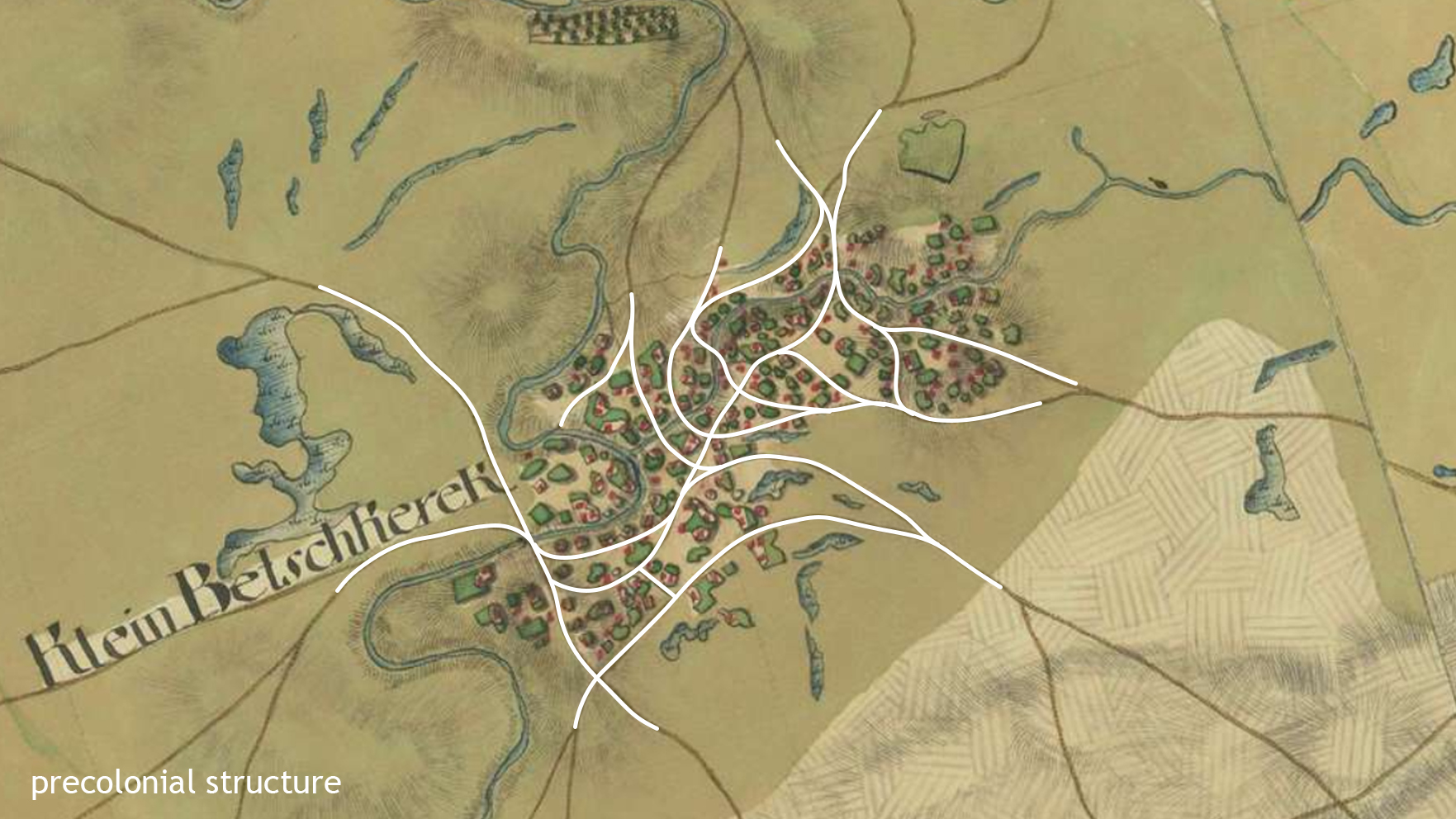

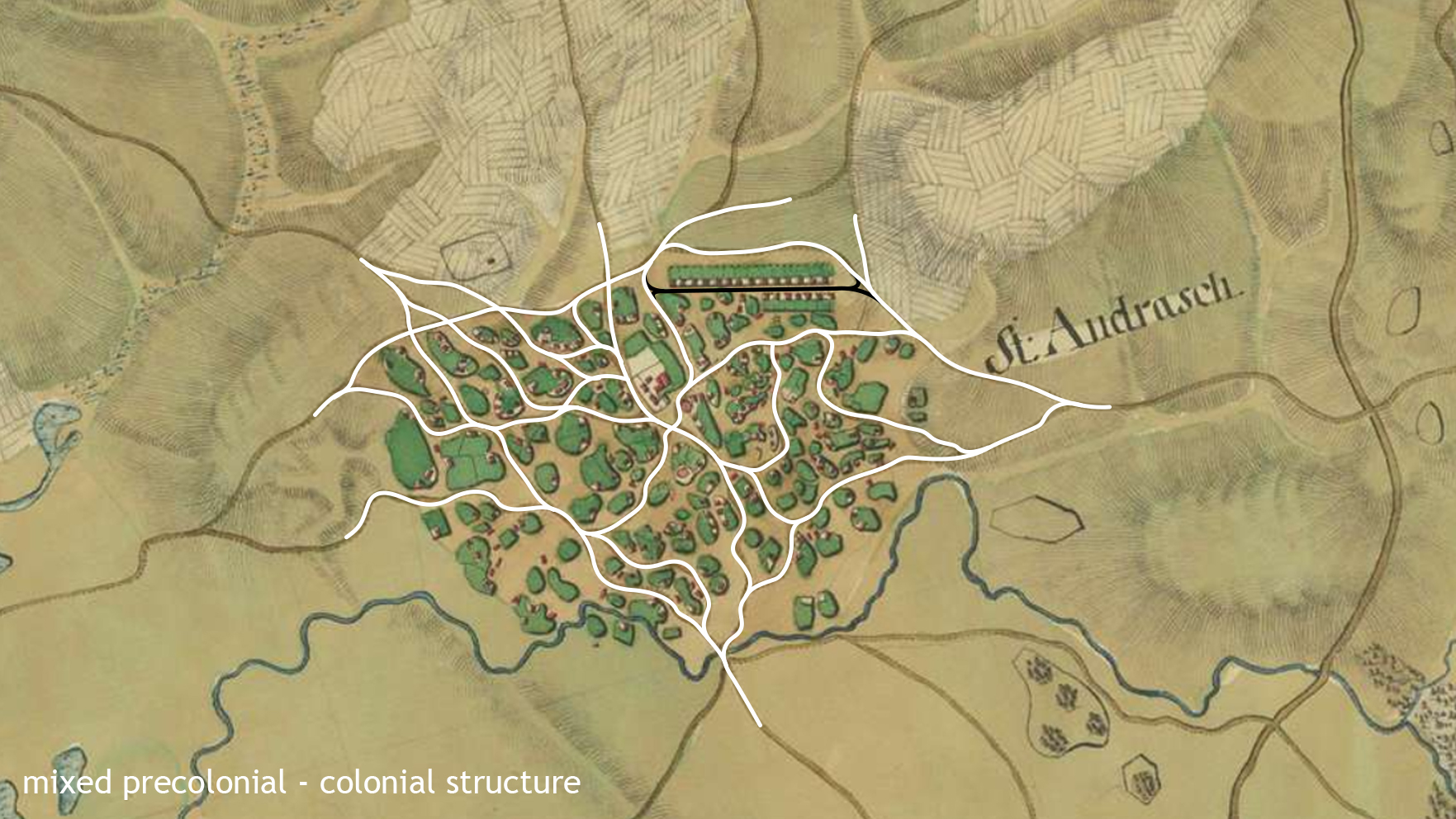

The distinction between colonists and the local population is further mirrored through the urban form adopted by colonial settlements, which generally opt for regular, geometrical patterns, in visible contrast to the usually organic structure of the existing localities. Enter the grid – the almighty instrument, which allows settlers to create easily controllable and recognisable structures in a foreign land.

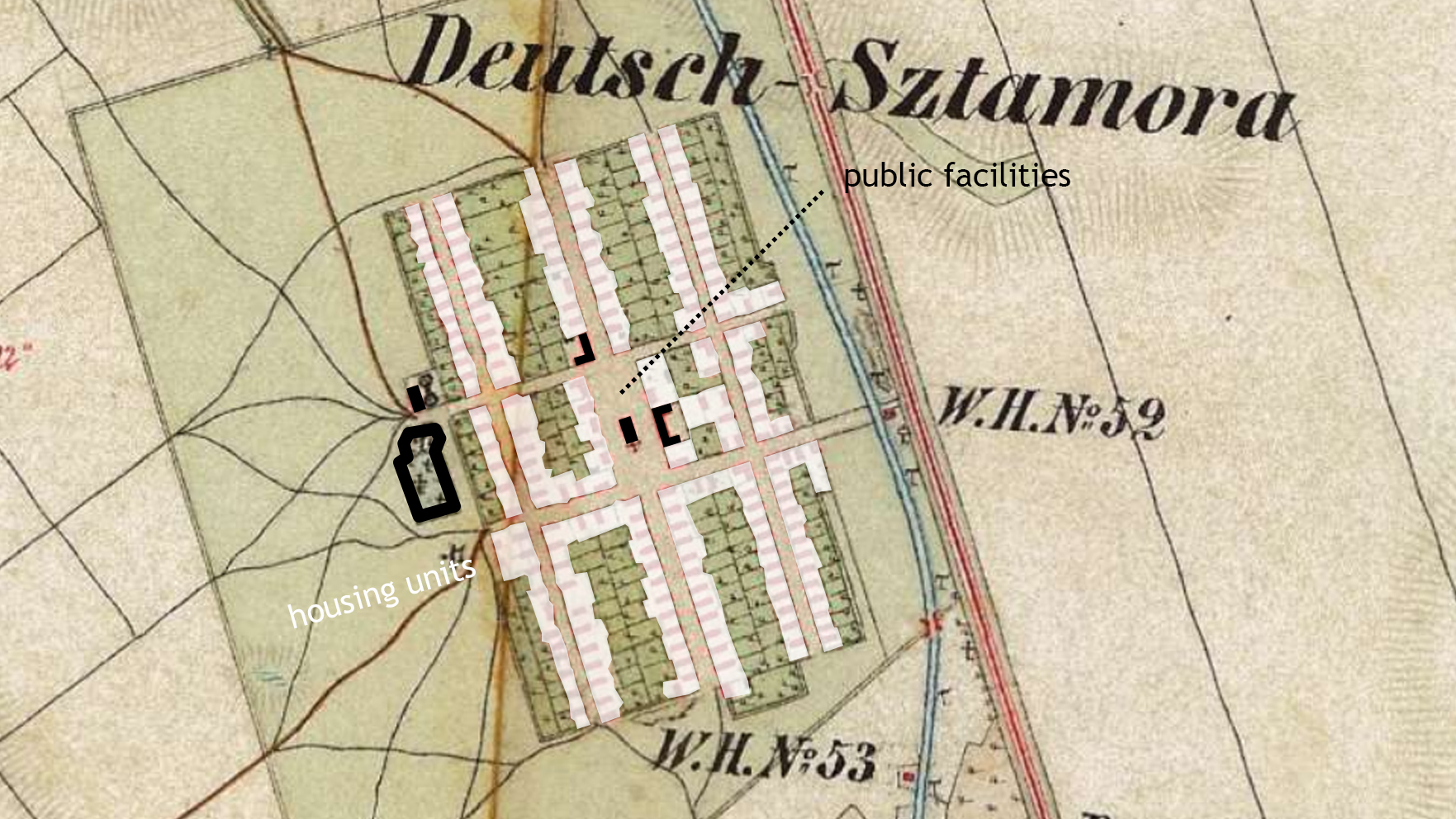

Figure 2.1 : Contrasting urban forms – colonial settlements vs. organic structures (schematic representation):

First Habsburg Topographical Survey / Josephinische Landesaufnahme (1769-1772), retrieved from mapire.eu

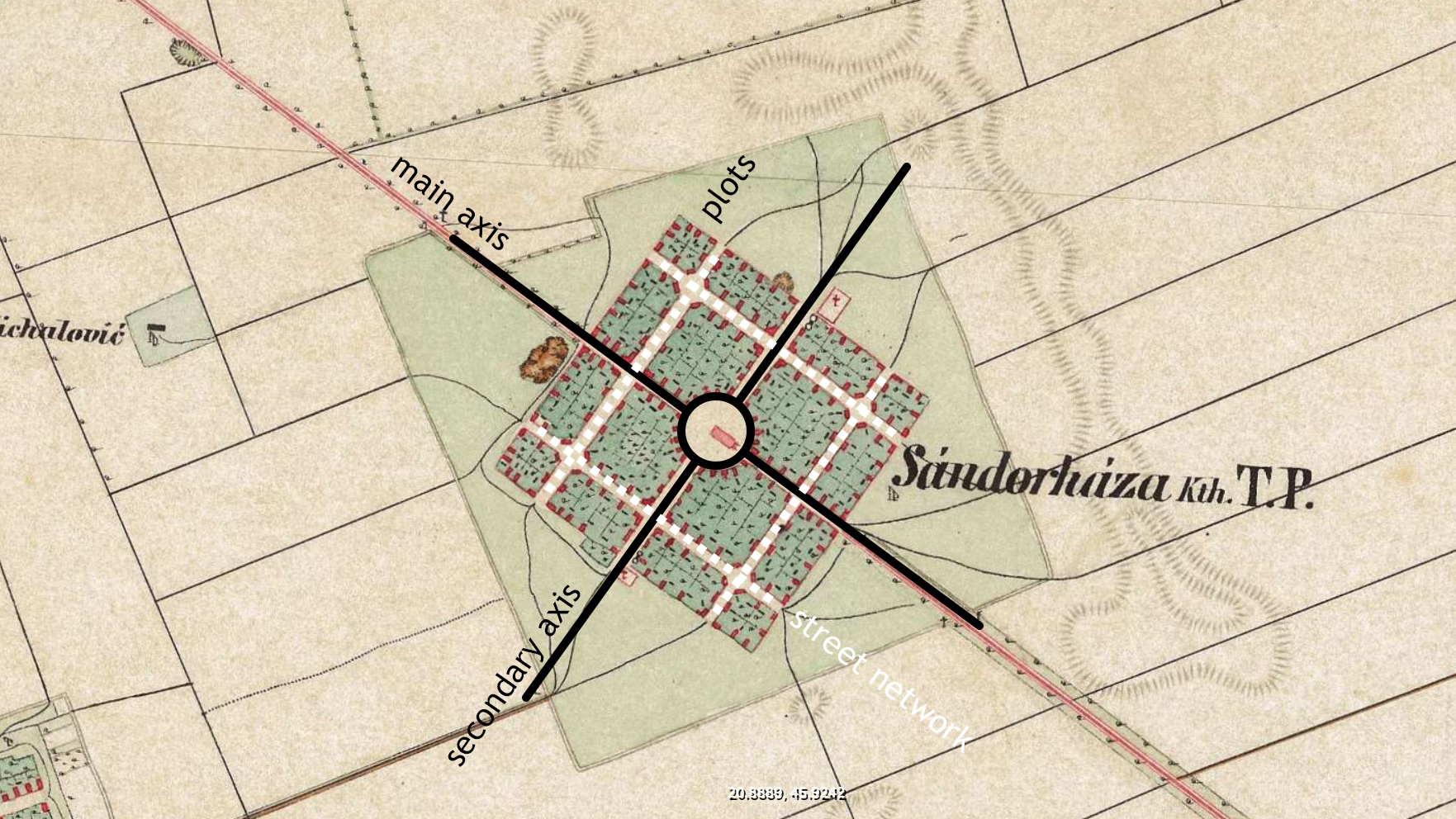

As for the colonial settlements developed under the Hapsburg rule in the newly-conquered territories[1], one can thus observe that these are always developed following a grid-like street network, which results in a relatively uniform urban fabric, usually built around a main public space and organized along one or two main axes. The rest of the streets are organized hierarchically in relation to the main axes (being either parallel or perpendicular to them). The blocks defined by the street network are further divided into plots (uniform in shape and size), which are then occupied with buildings (the closer they are to the center, the more important the buildings).

Figure 2.2 : Typical urban structure of a colonial settlement – main public space / main axes / street network / blocks & plots (schematic representation)

Second Habsburg Topographic Survey / Zweite oder Franziszeische Landesaufnahme (1806-1869), retrieved from mapire.eu

Figure 2.3 : Typical functional organization of a colonial settlement – clusters of public facilities / distribution of housing units (schematic representation)

Second Habsburg Topographic Survey / Zweite oder Franziszeische Landesaufnahme (1806-1869), retrieved from mapire.eu

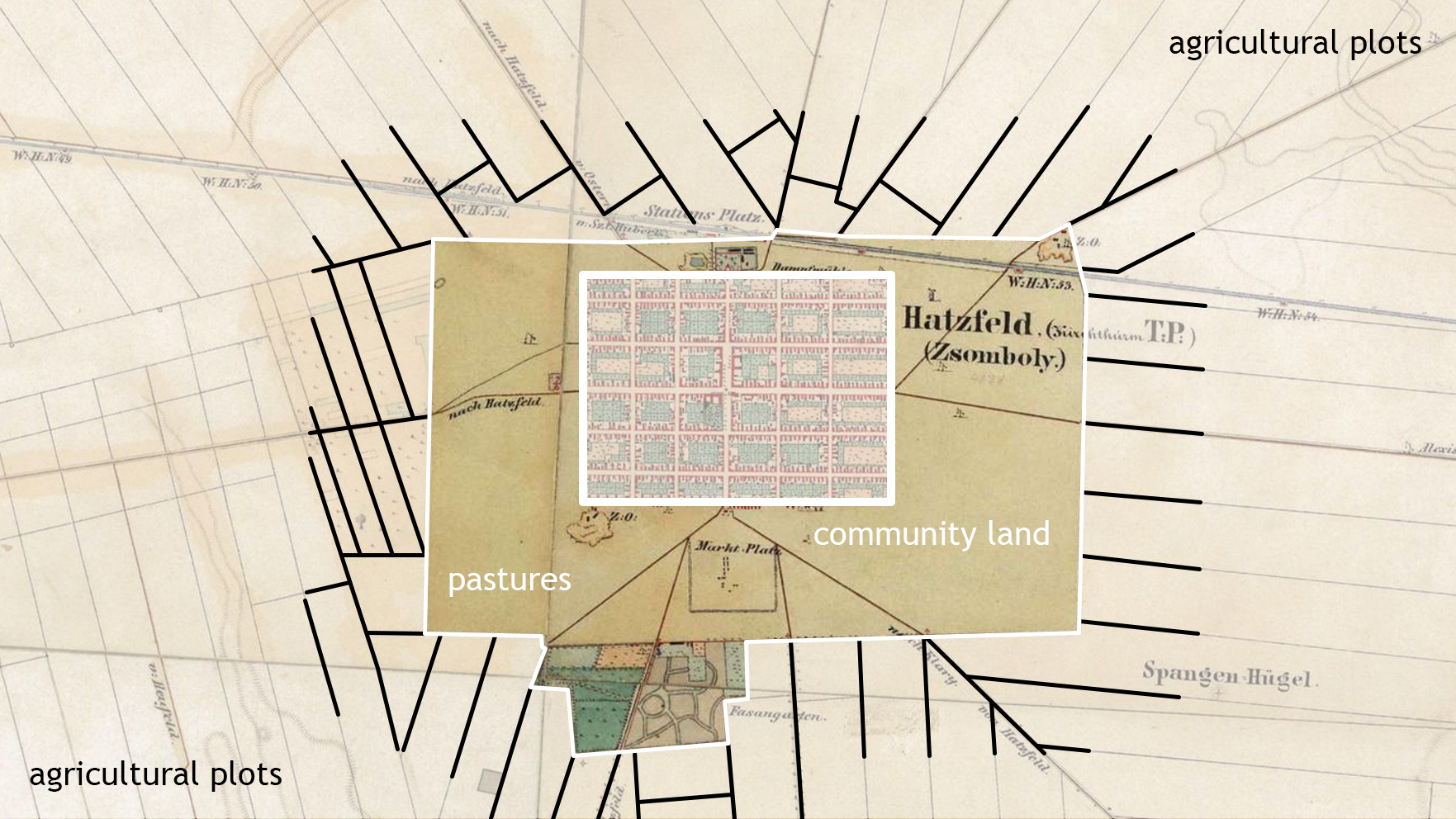

However, the power of the grid is not limited to the organization of the buildable area (or the intramuros) of a settlement. Its influence expands well beyond the limits of the urban fabric, governing the structure of the neighboring territory as well. Thus, the non-buildable area (or the extramuros) surrounding each settlement consists of agricultural plots (one for each housing lot), pastures (for animals) and community land, all organized following the same rules of regularity, axiality and proportion – but on a larger scale. It is thus ensured that the entire territory (and – most importantly – its resources) are properly divided between settlements and thus efficiently exploited and strictly controlled by a certain authority. At the same time, the division of the territory into regular plots, following the same orientation and proportion as the housing lots, but on a larger scale, allows for each locality to benefit from sufficient land to further expand in the future.

Figure 2.4 : Typical organization of the territory surrounding a colonial settlement – pastures / agricultural plots / community land (schematic representation)

Second Habsburg Topographic Survey / Zweite oder Franziszeische Landesaufnahme (1806-1869), retrieved from mapire.eu

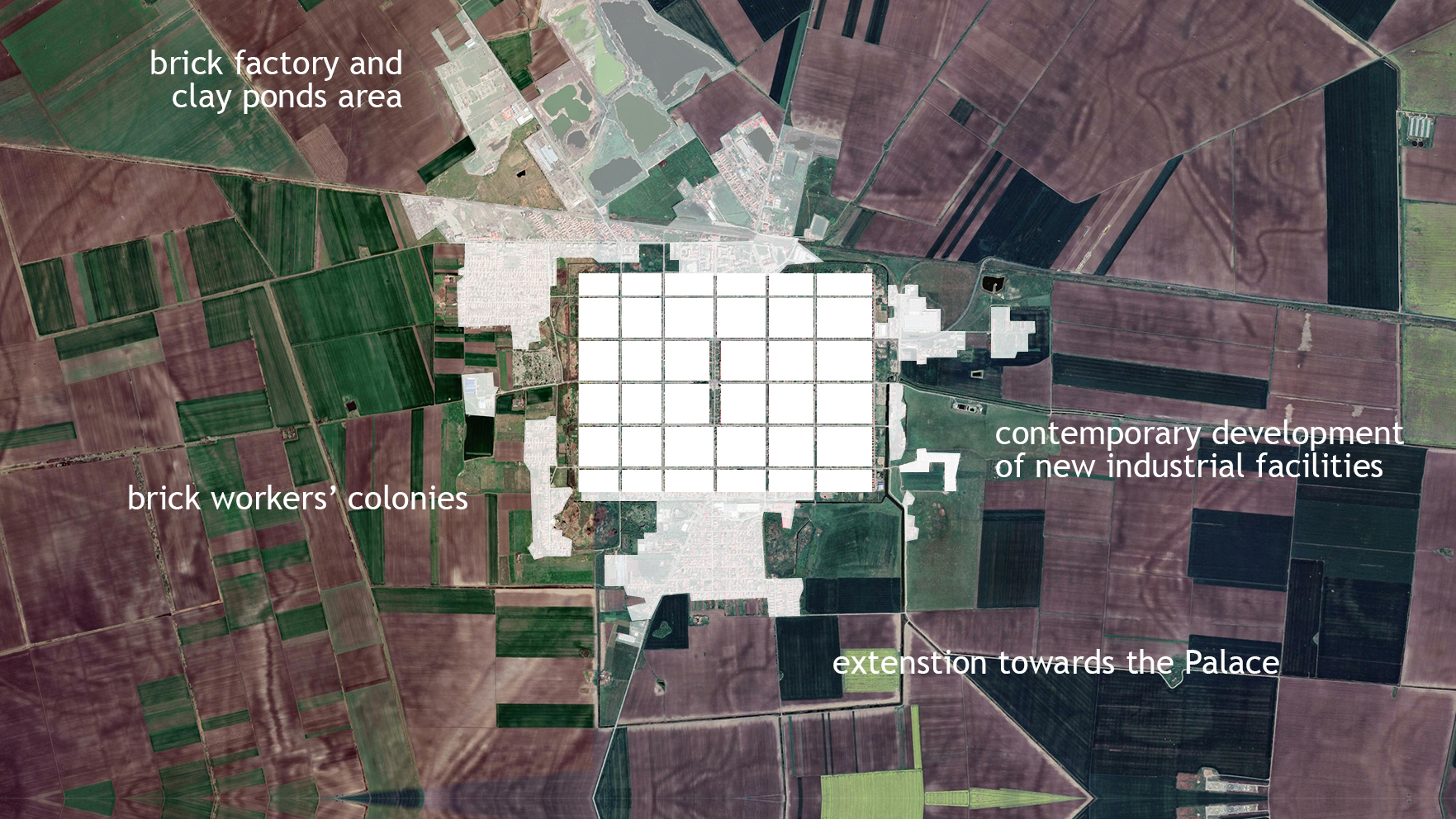

Figure 2.5: Typical evolution of a colonial settlement – through the staged expansion of the buildable area in the territory (schematic representation)

Present day satellite view, retrieved from mapire.eu

But the presence of community land – or commons, typically organized as a buffer between the buildable area and the agricultural plots surrounding it, represents what could be the most interesting feature of colonial settlements developed under the Habsburg rule. Designed as a functional area for the entire community, this land would typically be utilized by the local residents, in order to accommodate important objectives or events.

Among these, one can count infrastructure works (like the hydrographical regulation systems of Banat), facilities for the exploitation of the existing resources (like the clay pits of Banat – or kaule – that provided settlers with the much needed building materials for their houses), as well as designated areas for the organization of community fairs / marketplaces and even cemeteries.

Case study (Kaule and areas of Commons in Jimbolia)

Jimbolia’s first settlers, coming from Mainz, Trier, Sauer, Pfalz, Lotharingia and Luxemburg, arrived in 1766, to a setting similar to the one described above. Their first colonial houses were made using rammed earth techniques. The raw material was extracted from the immediate vicinity of the locality. There, in the area of commons surrounding the settlement, at the end of each street, colonists would get their building materials by digging up clay pits named kaules.

A typical colonial house was made by compressing clay mixed with straw in a formwork of wooden planks. Oak wood, cut during the winter season, was generally used, but since this was a scarce resource in the area, even imperfect and bent planks were accepted. The inserted material was then trampled by foot or with special tools. The thickness of these walls reached around 40 cm. Once the entire house was erected, and the planking removed, openings for windows and doors were cut using special saws.

Over time, as colonists sought to increase their comfort, new building techniques became customary. As rammed earth dwellings were gradually being replaced with new ones made of bricks, an entire new brick manufacturing ecosystem appeared. It is assumed that the last craftsman to use the rammed earth technique was Nikolaus Schwarz, who emigrated to the United States in Chicago. (1) The kaules however, retained their function as main source for raw material, even as bricks were now being produced on a regular basis.This is evident on the third military topographical survey of the Banat region (1869-1887), with kaules clearly drawn out at the end of each street, not only in Jimbolia but throughout all villages around it.

These kaules had toponymic names. For example, die Kaul an der Electrisch was the pond near the Power Plant. In the 1950s, a sports field was to be built on the site of the lake to serve the Flamura Roșie handball team, which was, at the time, playing in the national handball league. Another name is Dampmillkaull – a pond near the mill. (1) Gradually, the kaules were transformed into a highly efficient drainage system, collecting rainwater at the end of each street along a canal that was hydrographically connected to the Mures- Bega basin. The canal was thus used in the control of water flows, insuring the locality against further flooding. Along it, a new natural ecosystem emerged, protecting the town from strong winds and blizzards.

Unfortunately, over time, many of these kaules have also been filled in. Several such campaigns took place in the 1970s when earth from the Ceramica factory (former Bohn) was used to cover some of the northern parts of the canal. A similar action took place around the 2000s, again in the northern part, between old Jimbolia and the Futok neighbourhood, in order to make space for social housing developments (ANL).

The kaules however still retain their symbolic if not functional importance. Previously, this functionality was diverse. They were commons, used for grazing, natural drainage areas, and idyllic landscapes exploited by children as their playground during the summer season, or for ice skating and hockey matches during winter. Currently, an edge phenomenon can be observed along their topography. With nature slowly re-conquering their topography, the kaules mediate the tension between urban development and the intensive exploitation of agricultural land.

Chapter 3. Colonization of the historical region of Banat under the Habsburg rule: networks and hierarchy within the territory

Teaching method: lecture – exemplification, case study

Duration: 45 min

The main purpose of this chapter is to further explain the principles of colonial territorial planning under the Habsburg rule, by demonstrating their application through the case study of the historical region of Banat[2]. This area was profoundly impacted by the systematization process coordinated by the Habsburg Empire following the conquering of these territories from the Ottomans and their subsequent colonization with German population, from the beginning of the 18th century onwards[3].

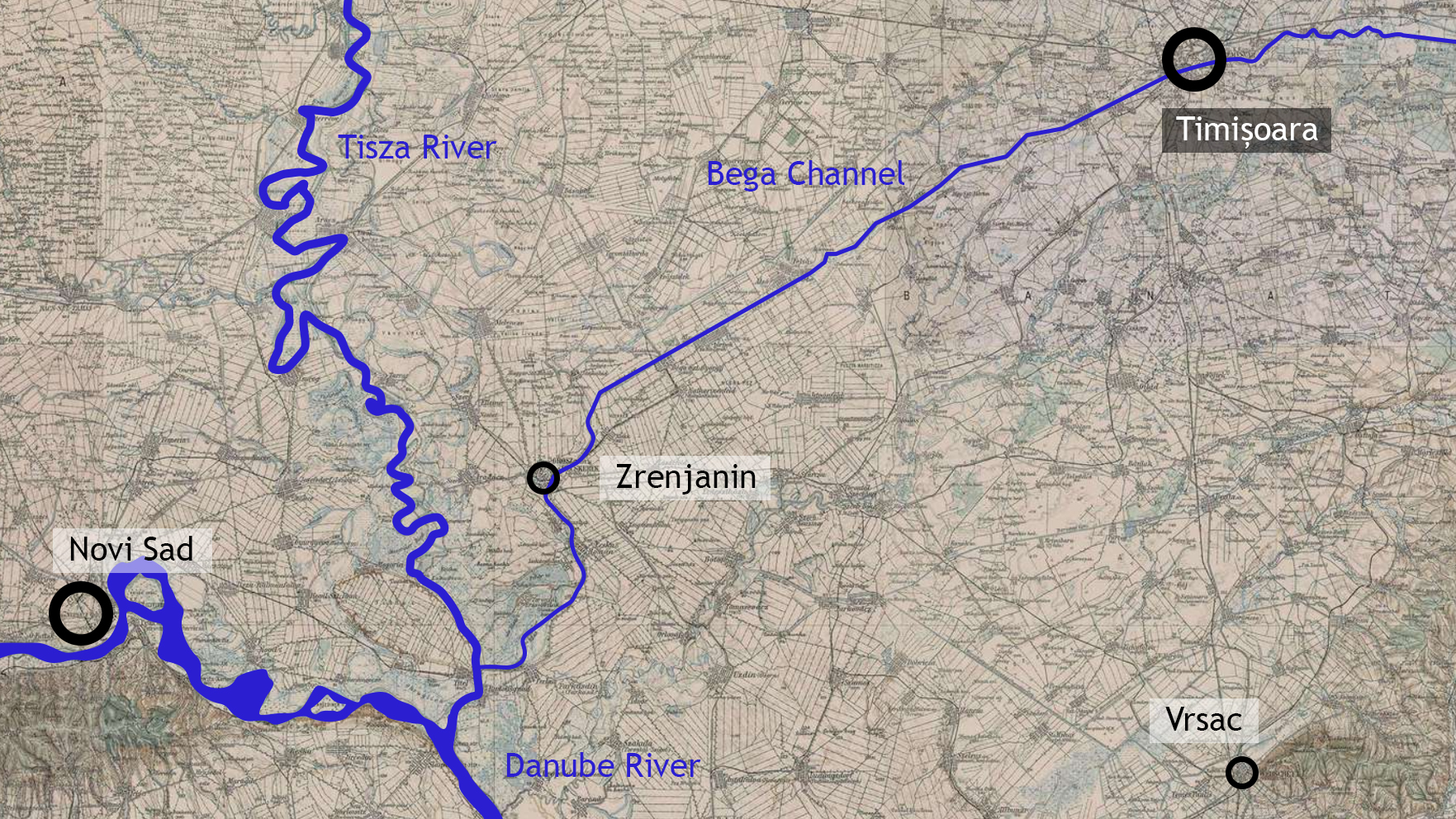

This chapter therefore concentrates on analyzing the theoretical principles in relation to their application within the historical region of Banat and their subsequent adaptation to its particularities, offering a deep understanding of the physical implementation of the theoretical principles within a well-defined territory, in relation to its geographic, economic and social particularities. While the latter are the result of this colonial project, the former, geography, presented planners with an a priori complex condition that needed to be tamed. This was addressed through a massive hydrographic project, its imprints still visible today, that shaped and organized the larger territory. As such, extensive technical works occurred during the 18th century, in order to drain the former marshlands and regularize the multiple water courses passing through the area. Finally, the Habsburgs concentrated on developing the accessibility towards Central Europe, using navigable routes[4].

Case study- The evolution of the hydrographic landscape in Banat

Geographically, the Banat region, part of the larger Pannonian plain, presents us with a very interesting case. Its current geographical features are the result of millions of years of erosion and interaction with reatring waters. 10 million years ago the very ground we are looking at today, was more than 100 meters below sea level. Around that time, the Pannonian Sea covered an area corresponding today to the land masses of: Hungary, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Austria, Slovenia (Figure 1). About 1,000,000 years ago an acceleration of the water withdrawal process began due to erosion and leaks towards other big water basins, like the Adriatic Sea, or Black Sea. 600,000 years ago the Pannonian Sea disappeared and only a series of large lakes and rivers remain in place. Almost 7000 years ago, the first traces of civilization were formed in the river basin of Banat. Another important testimony for the region are the Roman limes or rather the border of the Roman empire of the first century AD. It was built in relation to these preexisting waterways that were generally considered as being natural defensive structures. Later on, in the medieval period, many of the localities of this region were still being developed considering the water network of these river basins. The Ottoman urban settlements of the XVIIth century in particular, were very well connected to this landscape, showcasing an organic configuration and spatial disposition that was in tune with these waterways. All this however changed with the arrival of the Habsburgs. Their massive colonization project was based on a modern “reading” of this ancient landscape. The new economic project, designed for the newly acquired imperial region, meant that the existing geography, its nature, had to be tamed, subdued, along new, practical and functional, teritorial layouts. As this entire geography was now under the scrutiny of economic principles and needs, large-scale drainage works were initiated throughout the region. These were implemented with technical assistance provided by the Dutch engineer Maximilian Freymoth. These huge infrastructural works started in 1757 and continued until the end of the 18th century. In spite of these, large floods, some covering over 285.000 hectares, were still frequent in the Banat Region. Ironically, some of them were the direct effect of this huge economic endeavour, being caused by the irrational exploitation of the ancient forests covering most of the Timiş – Bega basin. Wood, used for coal, or as building material was a prime resource in the colonisation process. To prevent further flooding, from the mid XVIIIth century, the Hungarian administration continued the extensive works needed to regularize several rivers, through riverbed correction works and building of much needed dams. In fact, as we shall see further on, it was just such a major flood, impacting the city of Szeged, that led to the rapid development of Jimbolia’s brick manufacturing industries.

The beginning of the 20th century brought important investments in the hydrographic system. Locks, hydrotechnical nodes, micro hydropower plants, were implemented throughout to such an extent that this period is considered to be referential for the development and modernisation of these basins . Navigation on the Bega channel greatly increased, thus transforming this waterway into an important corridor for transporting goods and construction materials. Besides the existing road network and the railway network, the addition of the navigable Bega canal greatly enhanced the region’s economic viability, and attractivity, the length of its markets and supply chains, especially in relation to other regions in Central Europe.

Following the peace conferences concluding the Great War, the Banat was partitioned mostly between the Kingdom of Romania and The kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. The Agrarian reform, the economic crisis and the exchange of property between the former landowners, now captive between two new countries, had a major impact on the former singular vision of this territory, halting regularization works. The period is mostly dominated by land and property exchanges, fueled by the massive exodus of industrialists as well as large estate holders from the region (Csekonics being one such example).

The regime change following the Second World War, further consolidated a centralist viewpoint on matters regarding the economic output of regions, this time, along the planning needs of the new communist states. This marks however a period of great development that is only now scrutinized and understood at its proper value. Hydrography became essential in implementing the economic goals expected from state planned agricultural activities. This can be observed in the careful planning and further expansion of hydrotechnical works, mostly implemented in the 1960’s. These works were needed for flood containment as well as large scale irrigation. By the end of the 1980s the region benefited from approximately 11,000 km of irrigation canals, dozens of pumping stations, all amounting to a perfectly functional system. The Banat plain consolidated its status as the best agricultural area in Romania, mirroring, in this sense the success of neighboring Vojvodina (Serbis). Even though the two regions, ( formerly part of the historic Banat), were administered by 2 different regimes, they offered a somewhat similar image, in respect to their agricultural outputs.

Unfortunately the decade of transition that followed the fall of communism, led to an accelerated process of degradation and even disappearance of several important components of this hydrotechnical heritage. Romania, especially, witnessed chronic incapacity in the management of these facilities. The absence of a clear heritage code tackling the ever shifting values ascribable to what we define as CULTURAL LANDSCAPE further increased the strain on these networks posed by the climate, social and economic changes that have reshaped the region in the last three decades. Intensive agriculture and the lack of investment is affecting not only the hydrographic system but the quality of the ecosystems naturally developed along its flows.

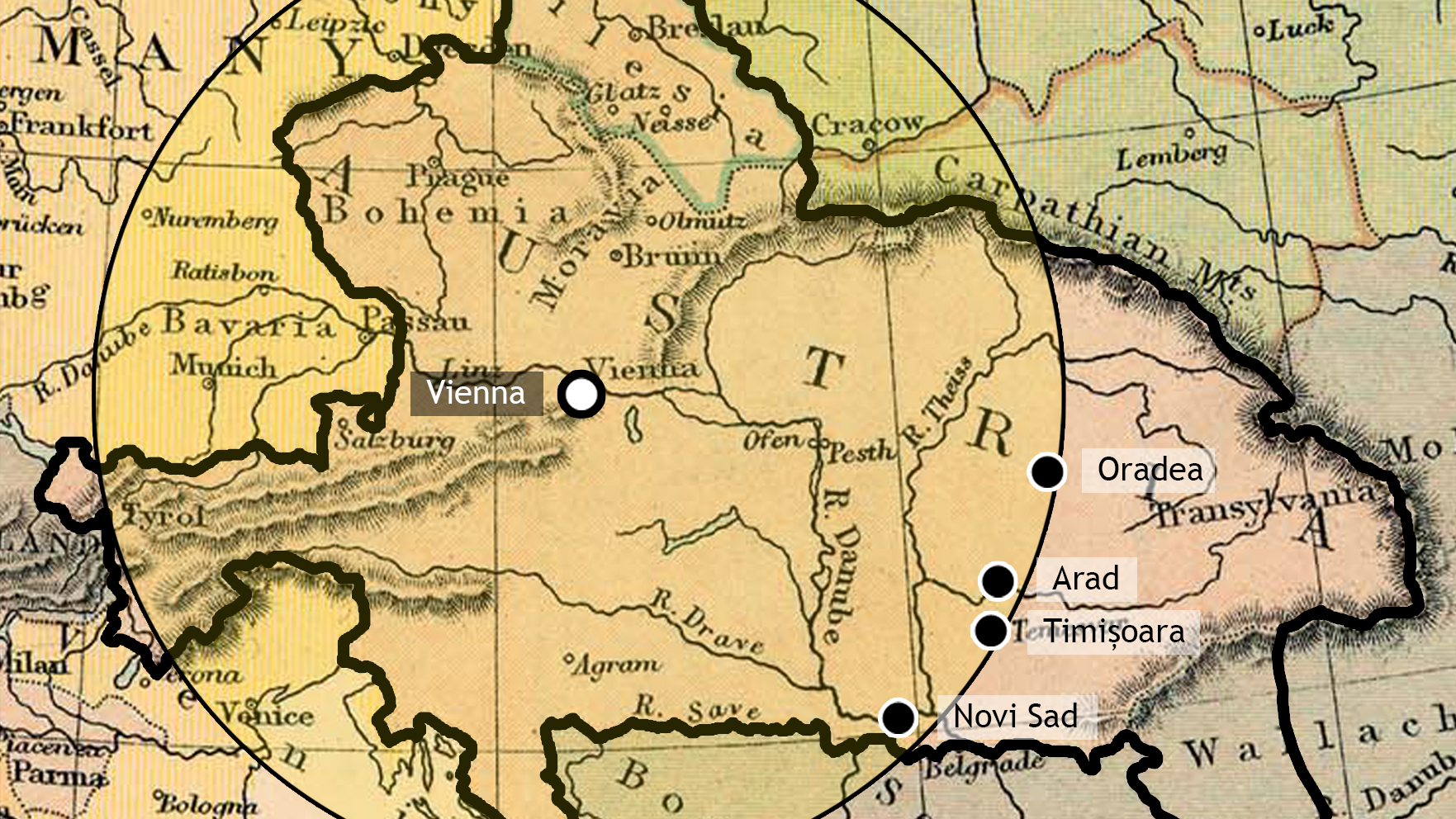

Figure 3.1: The position of the Banat region within the Hapsburg Empire and the key role held by the newly built Timișoara fortress in the empire’s defense network (schematic representation)

First Habsburg Topographical Survey / Josephinische Landesaufnahme (1769-1772), retrieved from mapire.eu

Figure 3.2: The network of drainage canals developed in the Banat region in order to regularize the existing marshland and water courses (schematic representation)

First Habsburg Topographical Survey / Josephinische Landesaufnahme (1769-1772), retrieved from mapire.eu

Figure 3.3: The network of navigable canals developed in the Banat region in order to develop the accessibility towards Central Europe (schematic representation)

First Habsburg Topographical Survey / Josephinische Landesaufnahme (1769-1772), retrieved from mapire.eu

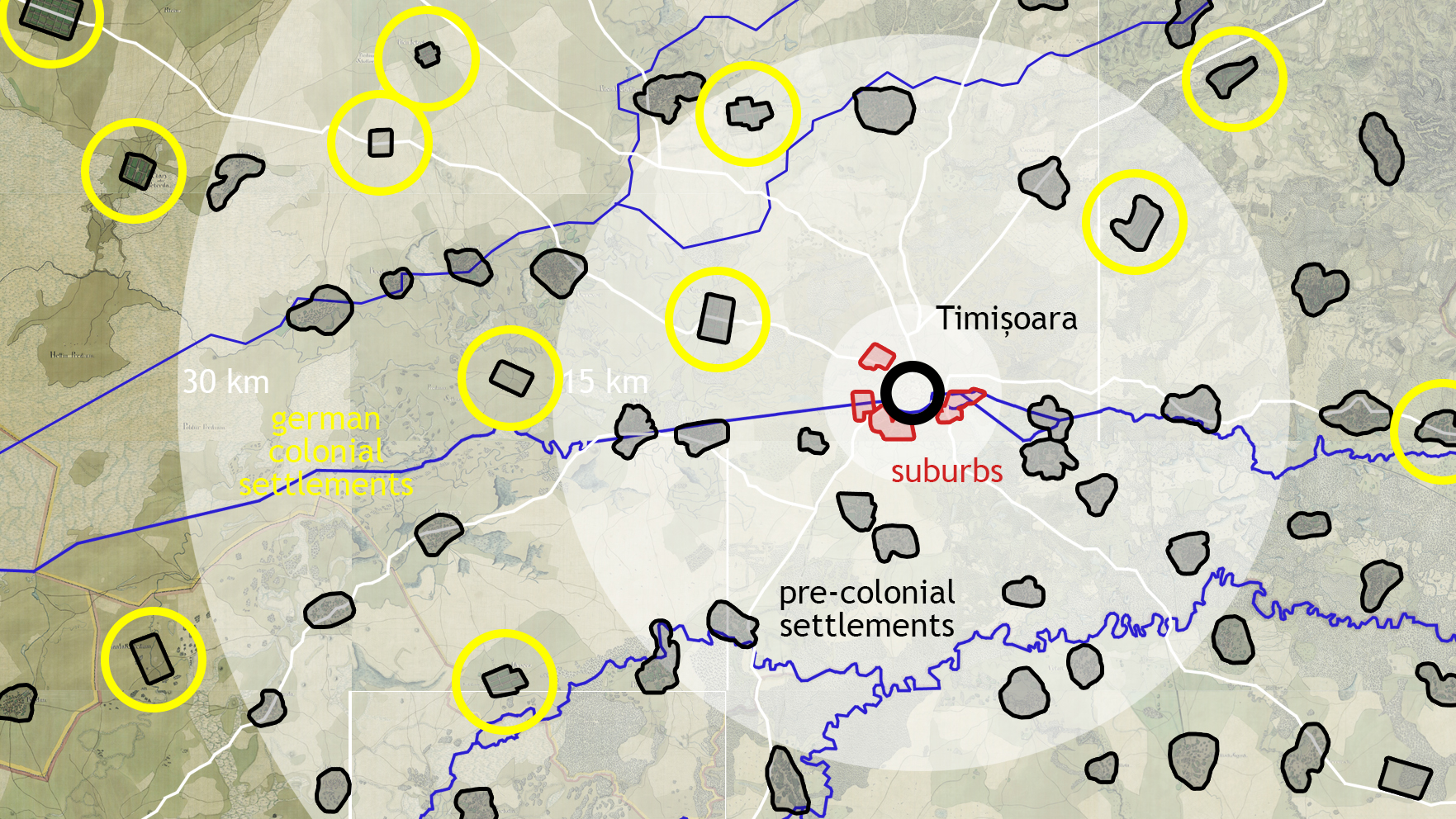

All these operations were implemented following the principles of colonial territorial planning, thus creating a complex network of settlements, resource exploitation facilities and communication lanes within the territory. Organized hierarchically, around centers of different levels of importance, this network spreads across the entire colonized region, allowing for the coordination and control of both material components (such as resources, land-use, urban structures) and immaterial ones.

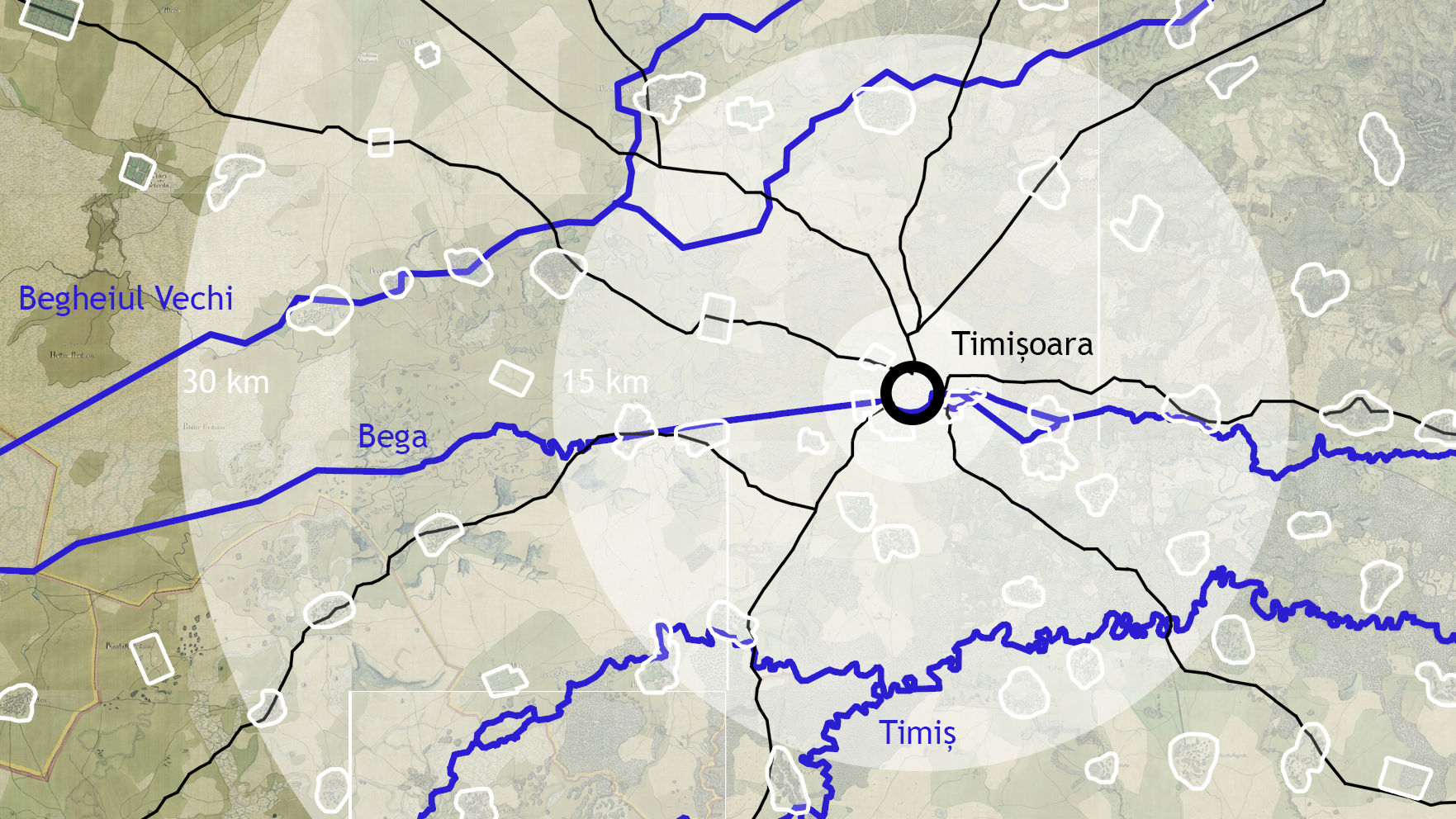

The network of colonial settlements that developed within the Banat region was structured around the citadel of Timișoara, which naturally held the most important position within the territorial hierarchy. Rebuilt as an ideal fortress, following Vauban’s model, Timișoara became part of a larger defense line for the Hapsburg Empire, together with Oradea and Arad (currently in Romania), as well as Petrovaradin (or Novi Sad – currently in Serbia). However, unlike its counterparts that developed a separate military fortress outside the town’s limits, the citadel of Timișoara also contained the urban tissue itself – with all of its functions, including the administrative headquarters for the entire region[5].

At the same time, the entire Banat region underwent a thorough process of restructuring and colonization with a muti-ethnic population. This meant that the existing settlements were either demolished and rebuilt from grounds up, or that their urban structure was gradually regularized – to the extent that they complied with the rules of colonial territorial planning[6]. At the same time, a number of new settlements were established within the territory, most of which concentrated along the main axis connecting Timișoara to Vienna and the rest of the Habsburg Empire (oriented towards North-West). Here, the grid takes center stage once again, structuring the settlements and the surrounding agricultural lands alike[7]. However, the orientation of the grid is not uniform across the territory, as it sometimes rotates to better adapt to the pre-existing structures (such as connection roads).

Figure 3.4: The network of colonial settlements developed in the Banat region during Hapsburg rule (schematic representation)

First Habsburg Topographical Survey / Josephinische Landesaufnahme (1769-1772), retrieved from mapire.eu

As for the initial planimetric patterns, it is worth mentioning that the colonization operation of the Banat region involved an open field laboratory, in which the efficiency of various planimetric configurations was tested. In fact, colonizations usually involve various waves of migration of a population that first settles in partially regularized and insecure planimetric structures in stage 1, followed by a rigorous planning of the built environment in stage 2 and a depletion of planimetric models in stage 3. The territory of Banat is thus systematized and densified with a network of settlements, located at uniform distances, in a hierarchy that establishes clear relationships between localities, based on their efficiency in resource exploitation. Around Jimbolia, we recognize, for example, settlements with a predetermined plan, that evolved however from organic structures adapted to topography (such as Kikinda), other localities with a predetermined plan that have maintained their coherence over time and, as expected, a series of localities for which the initial planimetric patterns are difficult to identify in the current morphology.

Figure 3.5: Three examples of colonial settlements established in the Banat region under the Hapsburg rule

First Habsburg Topographical Survey / Josephinische Landesaufnahme (1769-1772), retrieved from mapire.eu

The development of the Banat region, as well as that of Jimbolia itself, following the principles of colonial urban and territorial planning continued throughout the 19th century, under Hungarian rule, as well as during the early 20th century, once these territories were split between three countries – Hungary, Serbia and Romania. The following class (O1. M1.03 – Transformation and growth within the strict confines of the grid: economy, infrastructure and society. Case study: the urban development of Jimbolia throughout the 19th & 20th centuries) concentrates on the evolution of this settlement in particular, explaining the connection between certain growth triggers and its urban form.

Chapter 4. Colonial patterns and land-use: identification and interpretation of the implemented physical components

Teaching method: workshop – comparison of successive historical plans using a GIS-based application

Duration: 60 min

In order to better understand the colonial patterns and the way in which they influence land-use within the historical region of Banat, students will engage in a workshop, during which they will study the evolution of colonial settlements through the comparative analysis of their historical plans.

The following chapter therefore concentrates on helping students understand and recognize the physical components resulting from the actual implementation of the theoretical principles into practice, thus developing the ability to recognize and interpret physical characteristics of colonial settlements through the comparative analysis of successive maps.

Using a GIS-based application, students will overlap maps of the historical region of Banat from distinct periods of time, in order to identify:

- new settlements within the territory / settlements which underwent extensive works of restructuring;

- the systematization of the agricultural land in between settlements;

- the main connection routes (roads, navigable routes).

The exercise begins with setting the work environment:

- the visual support for the analysis: the present day map of the Banat region;

- the historical map(s) that is (are) to be overlapped: the First Habsburg Topographical Survey of the Banat region;

- the specific layers for every analyzed aspect:

- settlements – intramuros vs. extramuros (agricultural land / pastures / commons);

- resources;

- connection routes (roads / navigable routes);

- other technical works (drainage canals).

The exercise continues with direct observations regarding the implementation of the theoretical principles of urban and territorial colonial planning in relation to the realities of the historical region of Banat. Students are encouraged to interpret the physical characteristics of colonial settlements through the comparative analysis of historical plans, thus understanding the way in which the theoretical principles have been altered by the context in which they were implemented, as well as by the passing of time.

[1] In this respect, see also Clarkson, S. (2003). History of German Settlements in Southern Hungary, on www.feefhs.org (Foundation for East European Family History Studies).4 [2] In this respect, see also Thomas, C. (2009). The Anatomy of a Colonization Frontier: The Banat of Temesvar, in Austrian History Yearbook, 19(2) [3] In this respect, see also Bugaisky, G.; Stemper, L. & Tullius, N. (2007). The colonization of the Banat Following its Turkish Occupation, on www.dvvh.org (Donauschwaben Villages Helping Hands) [4] In this respect, see also Radoslav, R.; Bădescu, Ș.; Branea, A.M.; Danciu, M. & Găman, M.S. (2012). Sistemul urban Timișoara în epoca modernă, in Urbanismul Serie nouă, Nr. 12-1 [5] In this respect, see also Radoslav, R.; Bădescu, Ș.; Branea, A.M.; Danciu, M. & Găman, M.S. (2012). Sistemul urban Timișoara în epoca modernă, in Urbanismul Serie nouă, Nr. 12-1 [6] In this respect, see also Gheorghiu, T.O. (2019). The rural habitat and the Habsburg administration, in Neumann, V. The Banat of Timișoara: A European Melting Pot. London: Scala Arts Publishers Inc. [7] In this respect, see also Radoslav R., Bădescu, S., Danciu, M.I. (2014). Evoluția parcelării în relație cu extinderea aglomerării urbane Timișoara, in Urbanismul Serie nouă, Nr. 16-17

References

- Bugaisky, G.; Stemper, L. & Tullius, N. (2007). The colonization of the Banat Following its Turkish Occupation, on www.dvvh.org (Donauschwaben Villages Helping Hands), available at: https://www.dvhh.org/history/1700s/banat-colonization-after-turks.htm

- Clarkson, S. (2003). History of German Settlements in Southern Hungary, on www.feefhs.org (Foundation for East European Family History Studies), available at: https://feefhs.org/region/banat-german-settlements

- Thomas, C. (2009). The Anatomy of a Colonization Frontier: The Banat of Temesvar, in Austrian History Yearbook, 19(2), available at: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/austrian-history-yearbook/article/abs/anatomy-of-a-colonization-frontier-the-banat-of-temesvar/9FC5A42D0675C9B32AA0FC837A9D8AA9

- Gheorghiu, T.O. (2019). The rural habitat and the Habsburg administration, in Neumann, V. The Banat of Timișoara: A European Melting Pot. London: Scala Arts Publishers Inc.

- Gheorghiu, T.O. (2018) Mici orașe / mari sate din sud-vestul României. Monografii urbanistice. Bucharest: Simetria

- Radoslav R., Bădescu, S., Danciu, M.I. (2014). Evoluția parcelării în relație cu extinderea aglomerării urbane Timișoara, in Urbanismul Serie nouă, Nr. 16-17

- Radoslav, R.; Bădescu, Ș.; Branea, A.M.; Danciu, M. & Găman, M.S. (2012). Sistemul urban Timișoara în epoca modernă, in Urbanismul Serie nouă, Nr. 12-13

- Gheorghiu, T.O. (2011) Sistematizarea Rurală în Banatul Secolelor XVIII-XIX, in Urbanismul. Serie Nouă, Nr. 7-8

Other Instructors

Ioan ANDREESCU

Professor

Cristian BLIDARIU

Associate Professor

Oana SIMIONESCU

Teaching Assistant

Ana BRANEA

Associate Professor

Mihai DANCIU

Teaching Assistant

Bogdan DEMETRESCU

Associate Professor

Bogdan ISOPESCU

Teaching Assistant

Ștefana BĂDESCU

Assistant Lecturer

Dan Răzvan DINU

Assistant Lecturer

Syllabus

The aim of this class is to facilitate the objective understanding of a territory, through the analysis of the physical components that determine its structure. In the case of colonial settlements, these refer to the grid - the almighty instrument, which allows settlers to create easily controllable and recognisable structures in a foreign land. This course therefore concentrates on explaining the principles of colonial territorial planning, further demonstrating their application through the case study of the historical region of Banat. This area was profoundly impacted by the systematization process coordinated by the Habsburg Empire following the conquering of these territories from the Ottomans and their subsequent colonization with German population, from the beginning of the 18th century onwards. The colonial patterns and land use of this region are further analyzed within the ‘workshop’ component of the first course, through the overlapping of historical plans in a GIS-based application.

O1.M1 UNDERSTANDING THE TERRITORY AS A SYSTEM

O1.M1.02 The power of the grid: subordination and regularization in colonial territorial planning - Case study: the historical region of Banat under the Habsburg rule

Type of format

Lecture & Workshop

Duration

90 min lecture (theoretical notions) 15 min break 60 min workshop (case study)

Possible connections (with other schools / presented topics)

UAUIM O1. M1.01 Grids, Formal tools for understanding and manipulating space O1. M1.05 Borders- theoretical research framework SUSKO O1. M2.02 Introduction to GIS story maps

Main purpose & objectives

The main purpose of this class is to help students understand and recognize the various morphological features of colonial settlements, as well as the way in which these can evolve and adapt (as a result of the interaction between economy, transportation, health and human services, as well as land-use regulation). In addition, the class introduces objective methods by which students can understand the prospective evolution of a territory, helping them to acquire design skills in relation to a context that is stagnant, declining or increasing. Especially relevant for major infrastructure projects, single public objectives and repetitive ones (such as national / cross-border facilities and connections), this class offers the possibility of a realistic approach, adapted to the context and economic realities of a particular site. This course therefore concentrates on the following objectives: introducing students to a plethora of theoretical notions, regarding colonial territorial planning and the grid-like urban structures that they usually adopt; analyzing the theoretical principles in relation to their application within the historical region of Banat and their subsequent adaptation to its particularities; understanding and recognizing the physical components resulted from the implementation of these principles, through the examination of overlapping historical plans.

Skills acquired

Detailed theoretical knowledge regarding colonial territorial planning and the utilization of the grid in order to regulate and subordinate a newly-conquered territory Deep understanding of the physical implementation of the theoretical principles within a well-defined territory, in relation to its economic and social particularities The ability to recognize and interpret physical characteristics of colonial settlements through the comparative analysis of historical plans

Contents and teaching methods

1. The power of the grid: a short theoretical introduction Teaching method: lecture - theoretical approach 2. Colonial territorial planning under the Hapsburg rule: theoretical principles of urban development Teaching method: lecture - exemplification, case study 3. Colonization of the historical region of Banat under the Habsburg rule: networks and hierarchy within the territory Teaching method: lecture - exemplification, case study 4. Colonial patterns and land-use: identification and interpretation of the implemented physical components Teaching method: workshop - comparison of successive historical plans using a GIS-based application

Reviews

Lorem Ipsn gravida nibh vel velit auctor aliquet. Aenean sollicitudin, lorem quis bibendum auci elit consequat ipsutis sem nibh id elit. Duis sed odio sit amet nibh vulputate cursus a sit amet mauris. Morbi accumsan ipsum velit. Nam nec tellus a odio tincidunt auctor a ornare odio. Sed non mauris vitae erat consequat auctor eu in elit.

Members

Lorem Ipsn gravida nibh vel velit auctor aliquet. Aenean sollicitudin, lorem quis bibendum auci elit consequat ipsutis sem nibh id elit. Duis sed odio sit amet nibh vulputate cursus a sit amet mauris. Morbi accumsan ipsum velit. Nam nec tellus a odio tincidunt auctor a ornare odio. Sed non mauris vitae erat consequat auctor eu in elit.