O1.M3.05. Exhibition design – communication strategies

Free

About this course

Chapter 1. Introduction. A shift in the architecture exhibitions

Teaching method: lecture

Duration: 45 min

The first aim of this introductory chapter is to give a short overview on the relevance and power of influence of architectural exhibitions, and on the way their meaning has changed since modernity. This shift will be discussed by referencing some of the significant examples belonging to the modern and contemporary times and their background. Also, by exposing the particularity of the Romanian case-study, the chapter intends to tackle characteristics of the Eastern-European post-socialist context in order to emphasize the significance and place of architectural exhibitions nowadays, in a specific environment. A second aim of this chapter is to debate on the researcher’s attitude and towards their field of interest and the means of communicating it: exhibitions can be the (open) end of a research process, and have the ability to deliver a specific message (curatorial statement) to the public. This creates the framework for the further chapters / lectures.

Exhibiting architecture became a practice used by architects since the beginning of modernity, escorting the development of modern architecture. The first exhibitions with a major impact, such as the Great Exhibition, the Weissenhofsieldung, or the Werkbund, were all focusing, through projects or theory, on the idea of progress due to the built object. And, even if exhibitions were grounded in questioning social issues, urban life conditions or renewal of the architectural aesthetic, solutions/answers came through concrete architectural products which embodied the architects’ visions for the future.

Today, the significant exhibitions of architecture have shifted their scope and means of communication, have contextualized the content, have widened and diversified the perspectives. Such events can be considered not only occasions for displaying end products and bold ideas, but also appropriate and creative environments for more open processes, allowing exploration and learning, questioning, and debating within the different levels of encounters between the professionals and the public.

We stand for using as an entry point into the subject of curating architectural exhibitions the shift from the architectural product as central focus to a more complex thematic as the core of the display, thus questioning the architectural reasoning and construction, contextualizing it and marking more clearly the connection between architecture and the active society .

An important part of this shift was perhaps the need to repair erroneous histories, materialized exclusively as vehicles for ideology and to inflict new life and context into old narratives. Several MSc programs point to the importance of this practice: Critical, Curatorial and Conceptual Practices[1], Curatorship of Architecture and Design[2], Curating Contemporary Design[3]. Another need might be to provide a means through which a more abstract content, like unrealizable architectures, ideas and visions for society, but also research projects could become visible and be partly experienced and debated with the help of the exhibition frame.

Presence of the Past, the first Venice Biennale of Architecture, which took place in 1980 represents without doubt a turning point[4] in the practice of curating architecture, very clearly illustrating the shift of perspective in exhibiting architecture. This major architectural event, exhibiting projects from different nations around the world, has opened the way for a new, critical approach by creating a framework, a theme, that is never just about architecture, but regards all aspects of society. In that sense, reviewing all the topics of the Venice Biennale from its beginning until today, is quite relevant following changes of paradigm concerning the role of architecture for society.

Going back to the 1980s turning point, there still remains a question regarding how much of this movement penetrated the Iron Curtain. Erosions in the wall dividing the eastern – western thinking are themselves subjects of research and debate.[5] A closer look over the specific Eastern-European context (with a focus on the Romanian case) will be displayed as it follows, in order to better state our present discourse. The infusion of the Postmodern criticism – generally speaking or with direct reference to the Venice exhibition of Portoghesi – manifested in most of the Eastern Europe countries, even if they had at that time only local relevance, and now represent only a rich terrain of comparative research. Critique – although especially focused on the thematic of the masshousing – was present in such manifestations; and in this respect there can be cited at least two case studies. The Architectural exhibition 78, organized by young estonian architect Leonhard Lapin in Tallinn[6], was centered on criticizing – through metaphorical paintings, drawings and photographs joined by a very strong message – the condition of the masshousing in Tallinn. The exhibition had a rather unfavorable reception, mostly from architects, but it eventually proved to be the opening path towards several communication channels in the Estonian society (Tallinn Seminar, Ehituskunst) in which, among architects, other professions were involved in debates around the built environment. Other reverberations of the Western movement are to be found in the series of exhibitions organized by the Czechoslovakian review Technický, entitled Urbanita, and held in 1986, 1988 and 1990. They were “both a forum for clearly-formed professional exchanges of opinion, and at the same time demonstratively turned towards the public”.[7] Sometimes this critical attitude was and is generally understood as a reaction not to the (modernist) architecture itself, but to its “socialist content”, the failure being often understood as a failure of the political regime and not of the architects and their products.

In order to open a possible path in understanding this perspective it must be said that from the very first beginning of the period 1945-1989 in Eastern European countries architectural exhibitions were used as propaganda instruments.[8] They were addressing the architects and the public through printed materials and especially through three dimensional models which were intended to confirm the role of the architecture as a proof for the political success. This attitude can be added to an overall rejection of the modern, socialist architecture that characterized the last two decades of the communist regime and that marked both architects and society.

This perspective introduces the Romanian manifestations through architecture exhibitions since the 1990s. In the immediate post-commnist period, a series of exhibitions[9] (of which the main organizer was the Romanian’s professional organization) were intended to recover what was unanimously regarded as the golden era of interwar modernist Romania, embracing a similar attitude as the other Eastern European countries.[10] But it is interesting to note the fact that the first manifestation held in Bucharest in 1990, entitled Status of the City, critically addressed a different thematic, intending to widely expose and debate the brutal transformations of Bucharest’s city center (based on the demolition of a large area of Bucharest) orchestrated by the dictator Ceaușescu.[11] The exhibition addressed the wide public and it is mentioned that it had a participation of 30.000 people, “to an extent with no precedent for any other Romanian art or architectural exhibition.”[12] For different reasons at that moment (than the postmodern attitude in the Western 1980s), the focus of the exhibition was on a lost on endangered heritage, revealing the historical evolution of Bucharest that dated back in the 19th century.[13] Beside historical maps, pictures and surveys made before the demolition by architecture students in the 1980s, real fragments of the old houses, columns, capitals and others were displayed, embodying relics of the collective trauma of Bucharest. It is reasonable to attach this to the general post-socialist context of the 1990s exhibitions aiming to expose in powerful displays the collective trauma of communism.[14]

The next decades came with a significant change in approach that could be seen as a maturity stage in this kind of enterprise. First of all, by adding the curatorship as a key element, which involved the increasing significance of the message delivered to the public. On one hand this meant shaping a different attitude toward the “communist” architecture based on complex research studies superposing different perspectives (of art and architecture historians, sociologists, general cultural field), not only praising its potential values, but also evaluating the perception over this architecture in time.

After being able to take more distance from complex and controversial subjects, exhibitions started to articulate discourses that addressed subjects with often divergent perceptions, and demonstrate well documented points of view. A relevant endeavor addressing the communist architectural heritage are the exhibitions and their connected events Enchanting Views (2014) and The Factory of Facts and Other (unspoken) Stories (2017)- curated by art historian Alina Șerban. Another important subject that the exhibitions dealt with is the the post-socialist condition. One of the examples to be cited here are Magic Blocks (2009) exhibition and publication tackling the issue of the mass housing heritage at different levels.[15]; or the initiatives Urban Activation in Romania (2011) suggesting effective models of recovery of abandoned spaces, and Beyond the City (2013) questioning the situation of post-socialist suburban developments (the main initiator of all these, previously cited is Zeppelin foundation). Last but not least, more recent manifestations brought different other levels on the public stage, first of all is the interest in bringing into discussion difficult and ignored issues placed at the periphery of the public discourse, but yet hiding deep and complex (socially – economically – culturally) thematic and a large recurrency in the territory. Here we will cite the exhibition Shrinking cities in Romania (2016) – curated by architect Ilinca Păun Constantinescu), which tells the story of a forgotten land (the profound Romania) in the aftermath of the post-socialist condition. The curatorial concept is based on revealing the objective truth by gathering different researched based professional perspectives; opening the gates to both professionals and random public; adjusting the message to different kinds of public by using several types of exhibits; connecting with the public; inviting debate by leaving the issues unclosed. Such an initiative is engaged in a contemporary attitude towards this kind of issue, in which different types of initiatives, belonging to artists that address social and architectural issues, can be cited: Post Industrial Stories (Ioana Cârlig), or Pride and Concrete (Petruț Călinescu, Ioana Călinescu), a projects that look into the effects of the migration on the built environment. The interdisciplinarity in addressing such a complex subject is taken further by Fading Borders, the Romanian Pavilion to the Venice Biennale of 2021, which that brings into light the complex relationship of Migration and the City by presenting two in-depth studies: Away by Teleleu – a journalistic survey of the lives of Romanian migrants within various local European communities; and Shrinking Cities in Romania by IDEILAGRAM – an extensive research on the various forms of decline of Romanian cities, targeting a constructive understanding of the urban shrinkage as a vector for modernization and innovation, re-use, alternative resources, artistic creation, and revaluation of interpersonal relationships.

The background of the ideas stated in this first lecture is adjusted to the specific Eastern European area due to the particularities of the area: either in terms of nowadays economic and social issues, or involving the common cultural background.[16] Furthermore, in the last chapter, the three dimensional model is considered and discussed as a relevant instrument of communication within architecture exhibitions, since it has the capacity to evoke explicitly and to create deep and direct relation with the different categories of public.

Chapter 2. Exhibitions as (end-of) research. Constitutive elements

Teaching method: lecture

Duration: 45 min

The aim of this chapter is to create a framework and identify the key elements in producing an exhibition that displays the results of architectural and urban research. In this endeavor, we start formulating a series of questions to what we consider to be a curatorial approach focused not necessarily on objects, but also on data ideas, texts, or immaterial elements that compose a research. Who conceives the exhibition? What is the prior issue of the exhibition? For whom is the exhibition intended? What is to be exposed? In fact all these questions reveal interdependent connections between the key elements which we define here as: the main “actors” in producing the exhibition (curators, researches and exhibition designers), the message (the curatorial statement), the public (recipient of the message) and the in-depth content (the material of the exhibition, which needs to be selected and displayed). In order to prepare for a real curatorial practice (such as the one that took place in Kikinda), the lecture will go through these key elements and illustrate them with examples of recent exhibitions.

- Main actors and their roles: researchers, curators and exhibition designers

The curator plays the role of an orchestra conductor in charge with mediating between all the other elements that play a role in an exhibition.“A curator is expect to act as thinker, a writer, a content producer, a manager of projects and, above all, a provocateur”[17] Even if we see the curator’s role as essential in conceiving and putting together the content, a clear line should be traced between the role of the curator and of the other creators of content. If for an artistic or architectural exhibition displaying end products, the creators of the content can be defined as the artists or architects themselves, in the case of a curating initiative that is backgrounded on a larger thematic (social, economical, environmental) and which uses architecture – urban and artistic methods- as the milieu of the display, the main creators of content can be, alongside artists, also researches who are producing a rough content derived or subscribed to the main thematic of the exhibition. While the products themselves and their final display is the work of a different team of artists, architects, designers in charge with adjusting the content in order to support and fit the message in a manner that guarantees its receival by the public.

While in the usual artistic exhibitions these roles are most often separated, in the recent Romanian architecture exhibitions mentioned in the first lecture, it occurred more than once that the initiator of the project, a group of architects, also curated and designed the exhibition. Such cases, with their advantages and flaws are illustrated by the example of On Housing (2018) exhibition at BETA, and Enchanting Views (2014).

- Message of the exhibition: curatorial statement

The red thread of an exhibition, the curatorial statement positions the content of the exhibition in order to appoint the relevance of the thematic for the public. Thus, the curatorial statement represents a synthetic (sometimes based on a metaphorical symbolic / approach) conclusion that raises questions, curiosity and solicitude and gives the public the reading keys for the exhibition. The message refers to the entire products of the exhibition and creates an attitude towards it.

Sometimes the message targets a change of perception concerning a subject that has already been labeled by society. Such a case is illustrated by the Shrinking Cities in Romania (2016) exhibition, aiming to create a positive perspective on a negatively perceived phenomenon. The motivation for this ongoing project was, on the one hand, to provide a clear picture of the current state of Romanian cities and, on the other hand, to demonstrate the extent to which the phenomenon is overlooked in the Romanian public sphere by the exclusive focus on growth processes in the public discourse. These aspects became the project objectives and helped formulate the message more clearly: to raise awareness about the overlooked phenomenon of Shrinking Cities in Romania and to state the resulting need to redefine the role of architecture and urban planning.

- Public. Recipient of the message

One could say that the public is the reception barometer of the exhibition.The content must be processed in such a manner that it touches the public’s interest. Therefore it is very important to previously analyze who will constitute the public of the exhibition, and to estimate how familiar the public is to the subject. This determines finding the appropriate means for addressing the public, by different means of display. A second issue that derives from here is to establish the levels of interaction with the public. This gives an answer to how much will the public participate, and how will they appropriate and empathize with the content.

Finally, by public participation, the exhibition can become an open-end process and can further contribute to the research. As examples, the „Info-collector” of the Shrinking Cities exhibition gathered in its mailbox thousands of short stories and remarks about the visitor`s hometowns. This on the one hand measured the impact of the exhibition, and on the other, laid the ground for continuing the research.

- Curating content (selection of information and means of display)

If usually artistic exhibitions display objects, which are linked and explained by the curator, in these interdisciplinary exhibitions, material can be very diverse: rough data, unprocessed sources of information,it can consist of texts, dates and facts, collected information of all media. Therefore, the curator’s job can be quite difficult in establishing the narrative of the subject and the conceptual framework of selecting and displaying this material.

Of great importance are the role of digital platforms and social networks, strategies and languages for display and communication, and the wide variety of media at use.

As examples, On Housing (2018) exhibition at BETA came as a result of a research that materialized in statistical data, interviews, plans, photographs, videos, sounds. The curating concept selects, separates and relinks the information from the perspective of the receiver and associates objective data with artistic production.

- Design of the exhibition: connecting information and space

Exhibition design should arise as the perfect response to a good definition of the curatorial statement, the selected content and a good understanding of the space where the exhibition is going to be displayed.

How does one discover the exhibited topic? The design is site specific, displayed within a determined space and,through its spatial dynamics anticipates the behavior of the public.

That is why exhibition design is a process, a multidisciplinary and integrative one, combining very different disciplines (graphic design, interior design, interaction design, multimedia and technology, experience design, video-audio, lighting) in order to create multilayered narratives around a theme or topic.

As an example, the Shrinking Cities exhibition is explained in three different places with three different audiences- and the way the design adapted to them: the Bucharest Contemporary Museum of Art, the Administrative Building in a former mining city, and the Venice Pavilion .

Chapter 3. Models and installations as instruments for display

Teaching method: lectures

Duration: 45 min

The following chapter aims to demonstrate through examples the potential of the model as an instrument of representation and communication in curating architecture.

The physical model has always been a very consistent way of communicating architecture to a general, unspecialized public. The direct visual and tactile experience of such a representation generates an instant complete understanding of the complex relationship between built volume and space. The diversity of approaches for an exhibition curatorship using models as instruments of representation and communication is huge. Very diverse goals might be achieved using this generous method of representation, starting from the accurate, technical model that shows in detail, with high precision, the past, present or future reality to the model that rather belongs to the artistic realm than to the architectural one, aiming to transmit symbolic meanings or envision a utopic future.[18]

In particular cases models get beyond their material consistency and migrate towards the status of artistic installations, highlighting immaterial values and unleashing rather emotions than pragmatic information for the spectators. As it was previously stated, the Venice Biennale is such an experimental field for models that go beyond their ordinary function and aim to communicate much more than just a physical form. A huge array of experimental models were used starting from the first architecture biennial.[19]

Depending on the material used, the models also communicate various values of the curatorial intention. Sometimes they get close to sculptures, passing into an artistic dimension, as is the case with Mateus’ curatorship in various exhibitions.[20] Working with more scales of representation offers the possibility of overlapping different realities that might convey a clearer vision on in-between statuses or intangible realities situated between the built and the lived[21]. The interactive dimension for the visitors might be frequently emphasized through the use of the model as the base of the artistic concept[22].

An example of a model that represents both a means of research, and a means of display within an exhibition, is given by the co-presence models of the Uranus Now project. One purpose of the project, focusing on the almost completely demolished Uranus neighborhood, in order to make place for Ceaușescu’s Palace, was not to let the collective memory of these destructions fade away. So, there was a need to address the subject to the general public, both to those who had lived through the atrocities, and to the young generation that knew too little about it. At the same time, most of the documented materials, besides archive pictures and interviews, consisted of drawings- plans of the area. Along with the specific research, two essential questions were asked: How do you present an annihilated world? How do you connect the inhabitants’ memories and stories of the old streets and houses with the current space? While the curators believed that nostalgic accounts or the display of archives and other records as such are no longer enough, they intended to take a step forward towards a symbolic and analytical reenactment of an erased urban reality. The keyword is co-presence: overlaying today’s reality on the erased past reality. Thus, they created the co-presence model, a large 3D effect superimposition of both realities, the old and the new, emphasizing the demolished areas. The viewers could thus localize which streets and houses used to be under The House of People, or Piata Constitutiei. The other kind of models were the scale 1:1 reconstructed fragments of the old houses, mounted in the exact former place of existence, whis is now to be found in a public space or on the property of some institutions in the area.

These installations also work as support for accessing information: archive images and plans, interviews with the residents etc. This overlapping of the two realities and the process of remembering was achieved not only for houses, churches, schools, streets and gardens, but also people and their stories. Using 3D and physical models and installations, the project symbolically brings back to life the demolished buildings into today’s world.

The particular case of site specific scale models of the territory was proposed to be used in the workshop exercise for the Triplex Confinium exhibition in Kikinda. This was considered to open a possible perspective in understanding territorial relations between settlements, industry, and national borders by examining them through a scale model of the territory constructed using on-site existing materials. In doing so a direct connection will be established between the minute and material qualities of the region and the large-scale geometry and fluxes that determine its evolution.

The method is based on putting together two means of exploring and defining a territory: land art and scale models. Site-specific land art as it has been practiced by artists such as Richard Long, Robert Smithson works with attention to detail, reusing local materials and a new synthesis between habitation and landscape. Land art is focused on objects, meanings and design principles as by-products of the experience of being on site. As far as construction techniques go, land artists have managed to achieve powerful spatial effects with very little means (ex. Richard Long, A line Made by Walking). Territorial models could easily be brought into the realm of land art as potential subjects for representation. The limitations and lessons of land art could facilitate new ways of looking at a territory and for decision making needed to reduce a complex geographical shape to some of its basic components, the idea of scale and representation of distance, fluxes and order.

Existing ideas, projects or proposals can be tested by being introduced within the logic of the model. The model can expand indefinitely to assimilate whatever type of material/element or symbolic object is considered relevant. The actions that will emerge during the expansion of the model have temporarily labeled scale comparison, pretext and object juxtaposition.

Scale comparison is based on the introduction of other elements into the model in order to emphasize the scale of representation. These can include regional elements of large scale reference points at an augmentative level: an airplane flying in the sky, the great pyramid of Giza, Central Park NY, etc. in order to create scale contrast and to “georeference” the actual location.

“Pretext” derives from the logic of the model being extrapolated, bits and pieces of the model can be placed in other locations of the city/landscape. Due to this method the model becomes an instrument for randomly moving about Kikinda and triggering unexpected encounters. Students placing small sculptures or representations of the territory in different parts of the city can also be a good conversation starter with locals. The representations of the model spread around the city and surroundings of the model space can become a communication system that might entice locals and visitors to go and find the epicenter of these small artifacts.

Object juxtaposition supposes that elements existent in the vicinity of the model can be absorbed as model parts. Visual collages where objects from around the model will be inserted in real photos taken from the road between Kikinda and Jimbolia. One could then imagine driving from Kikinda to Jimbolia through a territory dominated by a huge water tower.

Chapter 4. Workshop framework. Kikinda curatorial practice (method, instruments, steps)

Teaching method: workshop

Duration: 60 min

In the following the experience of conceiving the final exhibition in order to disseminate the Triplex Confinium project will be presented. The endeavor took place at the closing summer school in Kikinda, in april 2022. The presentation is intended to expose Kikinda curatorial workshop as a closed case study, but also to propose following this experience by a possible working format in the specific field of curatorship through architecture- exhibitions as an open end of a research. .

The Triplex Confinium collective exhibition activity at the end of the Kikinda workshop aimed at exploring, debating and then practicing curatorial basic notions in the spheres of architectural, urbanistic, social and artistic research. This process of curating was intended to be a collaborative practice: placing teachers and students on equal position in debating, experimenting and working together for the design and production of the exhibition. It was also a work in progress activity, given the need to debate, substantiate and test the knowledge of exhibition making.

Curating architecture and debating curatorial processes for architectural exhibitions was fundamented in the series of lectures and discussions with curators and active actors in the exhibition field, therefore generating new ways of understanding, discussing and presenting the main topics of the Triplex Confinium programme. Debating the previous experiences from the curators’ point of view shed light on the intricacies and nuances of creating an exhibition. A series of short lectures and presentations in which tutors within the Triplex Confinium Project and guests shared their experiences outlined the theoretical framework and referred to the constitutive elements of a curatorship approach (as they were previously described in chapter 2).

Starting from several recent curating experiences in Romania, Ilinca Păun-Constantinescu’s lecture emphasized the theoretical essentials in building up an exhibition concept and the importance of understanding the role and the interaction with the potential public. Daniel Kovacs discussed the Othernity exhibition in the Hungarian pavilion at the last Venice Biennale (2021) by raising the important questions in tackling a given topic and adapting it to a specific context; more in Kovacs presentation it was emphasized the relevance of the message as a turning point from a static view (exhibiting products of the architectural landscape of the former Eastern Europe) to a dynamic/pro active perspective (envisaged to imagine the future to be of this particular network of socialist building). In this respect also it is to be noted the relevance of the message transmitted to the public through the exhibition title (Ohternity) referencing the much debated socialist modernity. Levente Polyak’s intervention showcased diverse instruments used for documenting and communicating to the public various international research projects, while highlighting key steps for defining the role of the different media and also the possible difficulties in transmitting a message to a multilingual public. Alexandru Belenyi initiated the discussion around scale, model, installation and public space, and this debate was continued on various study cases by the UAUIM tutors and the students. Among the debates the most frequent example was the Venice Biennial as a main showcase of contemporary case studies in the fields of architecture and design and a main reference in curating architecture.During the further debates of the students and teachers, the main topics emphasized and applied as built-up exercises addressed: the significance and the need of clarity in the message to be transmitted to the public, the use of different types of media and content, the importance of adjusting the content and message to a specific public.

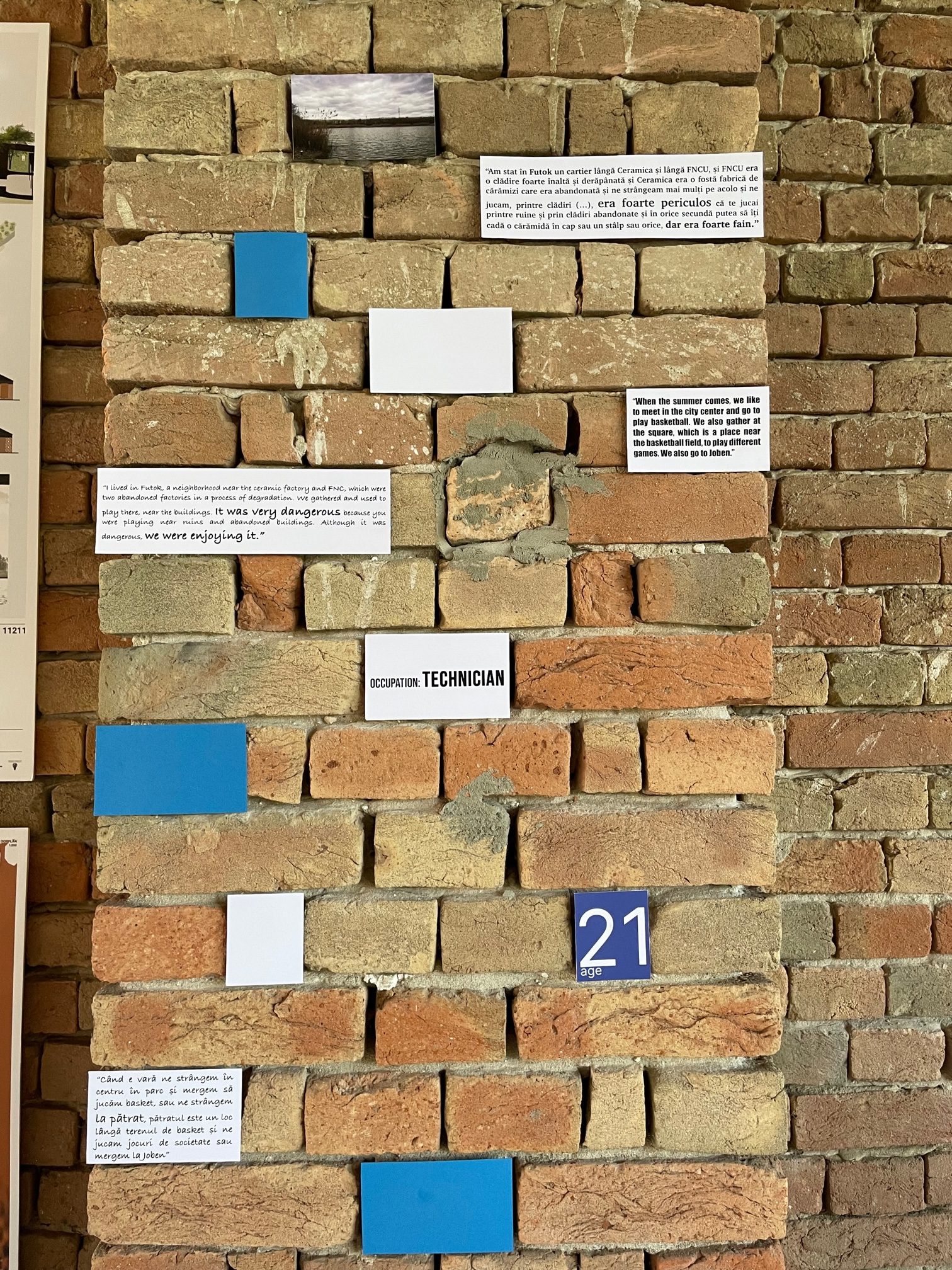

The exhibition organized in Kikinda had two purposes. First of all, it showcased the projects which have participated in the Think Brick competition in Jimbolia. Secondly, it included the processes and the results of the two workshops in Jimbolia and Kikinda, thus offering an overarching perspective on the Triplex Confinium project. The outcomes that resulted in both summer schools (Jimbolia, September 2021 and Kikinda, April 2022) represented the basis for creating both the frame and the content of the exhibition. The diversity of working methods and tools generating a variety of results (printed materials / installations / videos / texts / actual products etc.) helped in challenging different means of exposure. The significance and the clarity of the message for the public was also addressed by identifying specific titles and keywords that were common themes for the different workshops. For example, the idea of networking and mobility was presented in connection to the UBB workshop under the title “Mapping life histories: emotional places through interviews”, linked to keywords such as: lived spaces, interconnected lives, shared cities, social sciences methodology applied in architecture.

The main topics discussed during the workshops were tested in the course of building up the exhibition. The actual work for the exhibition involved clear phasing of the work and the creation of several mixed transnational teams (coordinators and students, different schools / different domains) with specific activities running in parallel: space survey, vectorization, cleaning and preparing materials, preparation and organization of the outcomes as film montages or significant quotes and images, mapping information (as physical and virtual exhibits), building the model and the attached installations.

The experimental potential of the site-specific, model-like format came to be one of the most important directions of the curatorship of the exhibition. Models and installations as communication tools were tested using spatial representation and also working with scales in representation. Initial proposal strategy of research and implementation revolved around the construction of a scale model of the territory determined by Jimbolia and Kikinda. In the scale of 1:1000 (or 1m in model scale = 1Km in reality) the distance between the two cities would have been roughly 20 m with the cities themselves being 3-4 m long. The aim of the exercise was to understand territorial relations between settlements, industry, and national borders. By making the model „outside” we looked to construct a direct connection between the small scale – minute and material qualities of the region (vegetation, soil type, debris) and the large-scale geometry and fluxes that determine its evolution. In doing so we would look for a synthesis between opposing scales – the material environment that surrounds each individual (small scale) and the abstract environment visible to us only through theory and conceptualisation (large scale). Existing ideas and projects could be tested by being introduced in the logic of the model.

The 3D model was, first of all, the construction of a new vantage point from which the two cities and the national border appeared together in a perceivable physical space. The scale of the model was in between the usual analytical categories as one can both walk into the model (like you would into an edifice or a piece of land art), but also see it from „outside” as an abstracted space of relations, fluxes and stories. By the end of the workshop the model expanded and included representations of other landmarks such as Mako and Domnești – nearby cities visited by the students as part of the social investigation and interviews exercise. As the objective of the model was to be constructed with local scrap materials from the area nearby Terra, it also became a pretext to explore the surrounding space and develop new means of abstraction starting from available materials. The models for Jimbolia and Kikinda were realized using brick – an abstraction technique that facilitated comparison and analysis of the two while for Mako and Dudești the abstraction vocabulary was expanded to include wood planks, broken sculptures or ceramic tiles. The color blue (tape, string, paint) was used first as a visual and eventually conceptual tool for enforcing unity upon the exhibition.

One of the main questions for students was how to represent key concepts like a grid that is a soft presence in the landscape and a border that separates and connects at the same time. The borders between the three countries were constructed as rows of bricks spaced apart so the boundary was a porous demarcation. The grid was represented as an absence materialized through the presence of urban blocks of the two cities. Triplex Confinium, the actual physical point where the three countries converge, was spatialized as a series of strings that connected the three parts of the same historical region.

The Triplex Confinium exhibition wasn’t seen only as a means to test and communicate the Triplex Confinium research, but also as a collaborative process of the seven partners and the local communities that goes beyond the outputs, a work in progress that extends both physically and virtually in the Banat region. Overlapping the lived and the built in Kikinda and Jimbolia in the brick installation and emphasizing potential connections of local communities led to a more profound reflection on the regional transborder network.The Triplex Confinium exhibition finalized as an interactive work in progress, placing the public as a performer and facilitating encounters for regional networking: visions for a common future. The content of the exhibition, the production of the last workshop in Kikinda and the connections created along the project led to find as essential a message of the exhibition the network, one of the key concepts of the Triplex Confinium project (synthesized in the students free exercise of materializing on site the position of Triplex Confinium).

[1] Columbia University, New York https://www.arch.columbia.edu [23.06.2022] [2] IUAV, Venice https://www.curatorship.eu/ [23.06.2022] [3] Design Museum London and Kingston University https://designmuseum.org/ma-curating-contemporary-design [23.06.2022] [4] Even if not perceived as such at the time, Presence of the Past exhibition was understood later as a seminal event since it represented the display of a consistent debate that was concerning the architects during the previous decade regarding the creation of a meaningful architecture for “ordinary users and occupants” (Adrian Forty, introduction to Léa-Catherine Szacka, Exhibiting the Postmodern, Ed. Marsilio, Venezia, 2016, p. 8).

[5] We cite here the exhibition entitled Lifting the curtain / Lever de Rideau, hosted at the 2014 Venice Biennale and centered especially on questioning the idea of the impenetrable Iron Wall. Based on a complex research, the exhibition displayed the eastern-western networks and connections existent in the second half of the 20th century. Also, in this respect, we cite the conference that took place a year later, entitled East West Central (Ákos Moravánszky, chair), tackling the same thematic area of the existence of a common ground, despite the politically bordered territory of Europe. [6] The exhibition was a peak moment for a series of similar manifestations, as Andres Krug, the author of some recent research on the subject is demonstrating. See: Adres Krug, “Courtyards, Corners, Streetfronts: Re-Imagining Mass Housing Areas in Tallinn” in Ákos Moravánszky, Kegler R., Karl, East West Central. Re-building Europe 1950-1990. Re-Scaling the Environment, Vol. 2, Ed. Birkhäuser, Basel, 2017, pp.233-251. [7] Benjamin Fragner, “Communication on the brink> Urbanita” in ***, 1945-1995 Czech Architecture, Ed. Obec Architektů, Prague, 1995, pp. 94-97. [8] It is of course to be noted that the practice of organizing great exhibitions (local, national or international, thematic or general) in which architecture (through the pavilions themselves or through the exhibits) was a very used practice during the interwar period, also a practice very much related to the authoritarian regimes. In the case of the post-war period it is also to be noted that the relevance of using architecture in this kind of exhibitions has different understanding for the 1950’s and for the years that followed the thaw (see for example the relevance of the Yugostavian pavilion at the 1958 Brussels exhibition). [9] We are referring here to: Horia Creangă Centenary 1892-1992 (1992), Bucharest in the 1920-1940s. Between avant-garde and Modernism (1993) and Marcel Iancu Centenary 1895-1995 (1996).

[10] Beside the later publication during the 1990s of several research books on different aspects of the eastern interwar modernism in different countries - as it is the series issued at MIT Press - it is to be noted the fact that at the international exhibition in Seville 1992, most of the pavilions of the eastern countries were reiterating the interwar modernist architecture. [11] The exhibition had as a continuation (1995-1996) the international competition București 2000, intended to find ideas for “healing the wound” in the heart of the city. [12] Alexandru Beldiman, „Alocuțiune scrisă pentru Simpozionul dedicat împlinirii a 125 de ani de la înființarea Societății Arhitecților Români”, București, Aula BCU, 26 februarie, 2016 în: http://arhitectura-1906.ro/2016/12/uar-octombrie-1990-octombrie-1999-primii-ani-de-dupa-revolutie/ [13] ***, “Expoziția «București - Starea Orașului»” in Arhitectura, Nr. 1-6, 1990, pp.16-19. [14] The Sighet Memorial could represent a relevant example in this case.

[15] Further details on: https://e-zeppelin.ro/magic-blocks/ [16] Beside the already mentioned Zeppelin foundation It is to be noted in this respect the relevance of different organizations present in the public space, concerned with similar issues, such as: KEK (Hungarian Contemporary Architecture Centre) or Polish Art Foundation, Platforma 9,81 or TRACE (Central European Architectural Research Think-Tank) and others, all opened to research and debate. [17] Definition given by the organizers of the Master in curatorship of architecture and design, posted as the main introduction to the presentation of the Master in curatorship of Architecture and Design. See further: https://www.curatorship.eu/ [18] As in Bodys Isek Kingelez’s works: while he occasionally referenced existing prominent landmarks, his architectural models/sculptures highlight an idealized version of the city; Bodys Isek Kingelez, City Dreams, May 26, 2018–Jan 1, 2019, MoMA, New York. [19] More details in the history of Architecture Biennial Venice, see Busetto, G., Bertelli, G., Lingeri, E. (ed.), Un secolo di architettura alla Biennale e in Europa, Marsilio, 2006. [20] Mateus, Francisco Aires, Book of Models, ArchiTangle, 2021.

[21] ADNBA, Hilariopolis installation, all paper, main exhibition in Arsenale, 2016 Venice Biennale, adnba.ro/project/hilariopolis---la-biennale-di-venezia-2016-curated-by-alejandro-aravena. [22] Ciprian Muresan, ”Bucharest City Model (fragment)”, 2016-2017, scale 1:330, cardboard, variable dimensions, in the exhibition #1.3 Ways to Tie Your Shoes, CONVENT, Ghent, Belgium, 2017; https://artviewer.org/ciprian-muresan-at-convent/.

References

- Mateus, Francisco Aires (2021) Book of Models. ArchiTangle.

- Watson, F. (2021) The New Curator: Exhibiting Architecture and Design. Abingdon and New York: Routledge.

- Hopkins, O. (2019) “Exhibiting Architecture: Between the Profession and the Public” in Architectural Design 89:6, pp. 68-73.

- Bujas, Piotr, Kovacevic, Igor, Meder Iris, Mrduljas Maroje, Szemerey, Samu, Vasourkova, Yvette (coord.) (2018) Lifting the Curtain.Lever de Rideau, Centre for Central European Architecture, Ed. Fourre-Tout

- Moravanszky, Akos, Hopfengartner, Judith (eds) (2017), Re-Humanizing Architecture, Ed. Birkhauser, Bassel

- Moravanszky, Akos, Lande Torsten (eds.) (2017), Re-Framing Identities, Ed. Brikhauser, Bassel

- Moravanszky, Akos, Kegler, Karl R, Re-Scaling the Environment (2017), Ed. Brikhauser, Bassel

- Szacka, Léa-Catherine (2016), Exhibiting the Postmodern, Ed. Marsilio, Venezia

- Obrist, H. U.(2015) A Brief History of Curating. Penguin Books

- Lamm, A. E. (ed.) (2015) Hans Ulrich Obrist: Everything You Wanted To Know About Curating But Were Afraid To Ask. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

- Lorente, A., Steele, B., Kyes, Z. (2012) Aarchitecture 17, London: Architectural Association.

- Log 20 (2010). ”Curating Architecture”. Anyone Corporation.

- Chaplin, S., Stara, A. (2009) Curating Architecture and the City. Routledge.

- Busetto, G., Bertelli, G., Lingeri, E. (ed.)(2006) Un secolo di architettura alla Biennale e in Europa. Marsilio.

- https://designmuseum.org/ma-curating-contemporary-design

- https://www.curatorship.eu/

- http://othernity.eu/

- https://cooperativecity.org/2017/06/03/funding-the-cooperative-city/

- https://fadingborders.eu/

- https://ideilagram.myportfolio.com/work

Other Instructors

Alexandru BELENYI

Researcher

Irina TULBURE

Assistant Professor

Irina BĂNCESCU

Assistant Professor

Ilinca PĂUN CONSTANTINESCU

Teaching Assistant

Cristian BORCAN

Teaching Assistant

Cristian BĂDESCU

Teaching Assistant

Syllabus

One of the main purposes of this course is to familiarize the students with the context of architectural curatorship as a current practice. Therefore divided into several chapters the course intends to: give primary notions related to the recent curatorial practice with a focus to the regional context; create a clear image on the specificity of the curatorial team and curatorial project with the help of a framework (constitutive elements) and to explain through details the possibility of working with specific architectural instruments for creating the final exhibits (the use of the three dimensional model). A second purpose is to create a framework for working in a potential exercise for curatorial practice (presented as a case study of a closed - exercise).

O1.M3 INTERPRETING AND WORKING ON HERITAGE OBJECTS IN THEIR LANDSCAPE

O1.M3.05 Exhibition design - communication strategies

Type of format

Lecture & Workshop

Duration

45 + 45 + 45 min lecture (theoretical notions) 60 min workshop structure (case study)

Possible connections (with other schools / presented topics)

O1. M1.01_UAUIM_Grids, Formal tools for understanding and manipulating space O1. M1. 02_FAUT_The power of the grid: subordination and regularization in colonial territorial planning O1. M1. 03_FAUT_Transformation and growth within the strict confines of the grid: economy, infrastructure and society O1. M1. 04_FAUT_Reinventing the grid: the thin line between relevance and oblivion O1.M1.05_UAUIM_On borders: a theoretical research framework. Border as a working instrument for design O1. M1. 06_BME_History Drawn in the landscape O1. M2.01_UBB_Tools for visualizing the urban geography of economic growth O1.M2. 03_UAUIM_ Process versus Object. Working with postindustrial communities O1.M2.04_UBB_ Speaking with communities O1.SUSKO / Geographical tools in Territorial Exploration O1. M3.01_DEB_Recognition by small scale intervention O1. M3.02.01_BME_Working with the (invisible) built heritage O1. M3.02.02_BME_Working with cultural landscape

Main purpose & objectives

One of the main purposes of this course is to familiarize the students with the context of architectural curatorship as a current practice. Therefore divided into several chapters the course intends to: give primary notions related to the recent curatorial practice with a focus to the regional context; create a clear image on the specificity of the curatorial team and curatorial project with the help of a framework (constitutive elements) and to explain through details the possibility of working with specific architectural instruments for creating the final exhibits (the use of the three dimensional model). A second purpose is to create a framework for working in a potential exercise for curatorial practice (presented as a case study of a closed - exercise).

Skills acquired

General knowledge regarding the current status of the curatorial practice through architecture within the regional context. Deep understanding of the issues regarding a curatorial project (constitutive elements, actors and their role in such an enterprise) The ability to find their own possible position in the context of such a project. The ability to adapt and to work in a multidisciplinary team for curatorial projects.

Contents and teaching methods

Chapter 1. Introduction. A shift in the architecture exhibitions: introducing references to the current practice in relation with the regional background. Teaching method: lecture Chapter 2. Exhibitions as (end-of) research. Constitutive elements: creating a theoretical framework of a curatorial project ain actors and their roles: researchers, curators and exhibition designers, message of the exhibition: curatorial statement, public recipient of the message, curating content (selection of information and means of display), design of the exhibition: connecting information and space, feedback and recurrency of the topic. Teaching method: lecture Chapter 3. Models and installations as instruments for display. Analyzing the possibilities of the three dimensional model as an architectural instrument with a great potential to be used as a final product of the exhibition. Teaching method: lecture Chapter 4. Workshop framework. Kikinda curatorial practice (method, instruments, steps) Illustrating a potential framework for a potential exercise through a closed case-study. This chapter opens a path for a potential workshop by creating a structure/framework. The specific exercise is to be organized according to the particular characteristics of the topic for the proposed exhibition. (the duration is evaluated in relation to the specific data).

Reviews

Lorem Ipsn gravida nibh vel velit auctor aliquet. Aenean sollicitudin, lorem quis bibendum auci elit consequat ipsutis sem nibh id elit. Duis sed odio sit amet nibh vulputate cursus a sit amet mauris. Morbi accumsan ipsum velit. Nam nec tellus a odio tincidunt auctor a ornare odio. Sed non mauris vitae erat consequat auctor eu in elit.

Members

Lorem Ipsn gravida nibh vel velit auctor aliquet. Aenean sollicitudin, lorem quis bibendum auci elit consequat ipsutis sem nibh id elit. Duis sed odio sit amet nibh vulputate cursus a sit amet mauris. Morbi accumsan ipsum velit. Nam nec tellus a odio tincidunt auctor a ornare odio. Sed non mauris vitae erat consequat auctor eu in elit.