O1.M1.07. The political economy of regions in Europe

Free

About this course

Content:

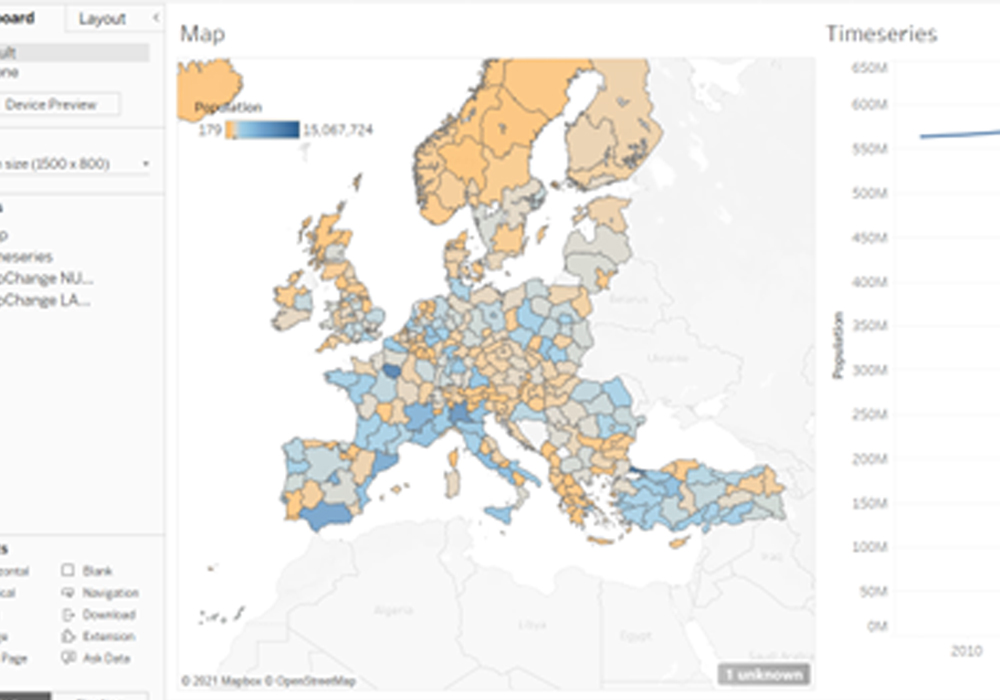

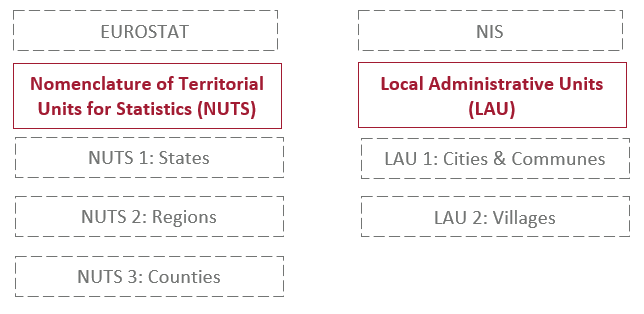

Eurostat provides statistical data using the Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics, organized at three levels: states, regions, and counties. National institutes of statistics provide also data at Local Administrative Units, at the locality level at two level of details (cities/communes and Villages). We discuss these issues. In addition an intermediate level is presented, that of the metropolitan areas and functional urban zones.

Content:

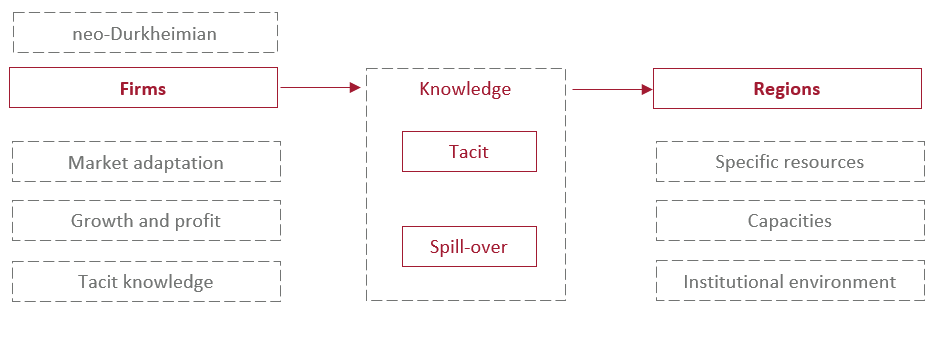

Knowledge (Boschma, 2004): Knowledge is a factor of production. Unlike capital and labor, the stock of knowledge is not reduced when it is used. On the contrary, knowledge accumulates over time through use due to learning from experience, trial and error processes, etc. This occurs largely within the firm: firms, for example, undertake research and development activities with the aim of creating new knowledge. Adaptive behaviour occurs because firms learn from their mistakes through trial and error or because they observe and imitate the successful routines of other companies. History matters in this regard.

Tacit knowledge (Boschma, 2004): Organizations build core competencies over time. Knowledge accumulates in the structure of organizations as embodied in routine processes and organizational procedures. The cumulative, localized, and tacit nature of knowledge has important consequences for the level of performance of firms. On the one hand, it benefits the firm, allowing it to exploit and further improve its competitive advantage. On the other hand, it can turn against the well-being of the organization (lock-in). This is called the competency trap: getting pretty good at doing anything reduces the organization’s ability to absorb new ideas and do other things.

Spill-overs (Boschma, 2004): Knowledge can of course spill over between organizations (labour mobility, supplier-buyer linkages, imitative behaviour of spin-offs). However, this is less likely to happen when the tacit nature of knowledge is emphasized. As a result, due to the cumulative, localized and tacit nature of knowledge, successful routines are difficult for competitors to imitate. Knowledge can be easily bought in the market. However, the market is not the most suitable mechanism for acquiring tacit knowledge because of the information asymmetry between the supplier and the buyer. The transfer of tacit knowledge therefore depends on reciprocal and stable arrangements, as cooperative relationships based on understanding and trust make it easier to bridge communication gaps. Knowledge creation is a cumulative, localized and interactive process that takes place within and between organizations and affects their level of performance either positively or negatively (lock-in). Firms’ competitiveness depends on both intra-organizational resources (embedded in routines and skills) and extra-organizational assets (such as complementary sources of knowledge and relational capital).

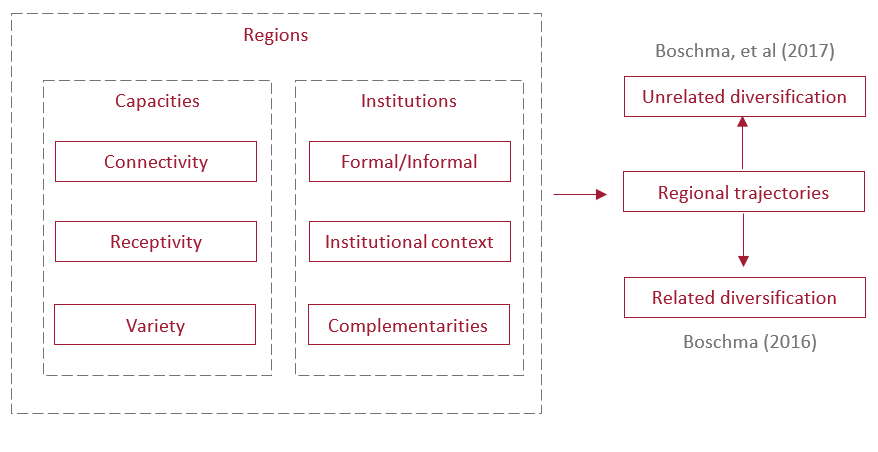

Connectivity (Boschma, 2004): The co-location of similar activities ensures that the successful experiments of local firms do not go unnoticed but are easily picked up at almost no cost. It’s about having access to information flows.

- The co-location of similar activities ensures that the successful experiments of local firms do not go unnoticed but are easy to pick up at almost no cost. It’s about having access to information flows.

- Network externalities: the more (potential) sources of knowledge in the territory, the greater the (potential) benefit for each local agent. Also, the more sources of knowledge in a region, the greater the number of (potential) connections with the outside world and the more information is available through extra-regional links with each local agent.

Responsiveness (Boschma, 2004): Local firms that share similar competencies in a particular knowledge domain will have better absorptive capacity and learning capacity than non-local actors. This has much to do with the tacit and idiosyncratic nature of knowledge: the effective transfer of tacit (ie complex, non-codifiable and contextual) knowledge requires a shared knowledge base, face-to-face interactions and mutual understanding and trust. Dense social networks, rather than regions, can be effective vehicles of knowledge creation and diffusion. Tacit knowledge is a common property or common good shared among members of an “epistemic community” or “community of practice”. However, because social networks are often (but not necessarily) geographically localized, knowledge spillovers are geographically localized.

Variety (Boschma, 2004): Too little cognitive distance means a lack of sources of novelty (a lock-in problem). The problem can be solved by a region endowed with a common knowledge base where organizations have access to diverse but complementary knowledge resources, either within the region or through extra-regional links. A certain degree of variety can lead to the development of clusters. Horizontally, variety among local competitors with similar capabilities in a cluster stimulates new experiments (triggered by local rivalry) while decreasing the risk of unwanted spillovers to rivals. Vertically, a high degree of specialization of firms in clusters implies that the knowledge base of each firm is sufficiently different that inter-firm learning can still occur.

Institutions (Boschma, 2004): Institutions as sets of shared customs, routines, established practices, rules, or laws that regulate relationships and interactions between individuals and groups. Formal institutions (such as laws) and informal institutions (such as cultural norms and customs) are both enabling and constraining factors for the innovation process and therefore form a major part of the selection environment for firms. The institutional environment affects the intensity and nature of knowledge creation and the (collective) learning mechanisms involved, such as the extent and nature of cooperation between firms. An institutional environment often consists of an interdependent set of institutions in a given region. Institutional complementarity means that the efficiency of one institution (for example, the way the labour market is organized) amplifies the efficiency of complementary institutions (for example, the way the financial market works).

Content:

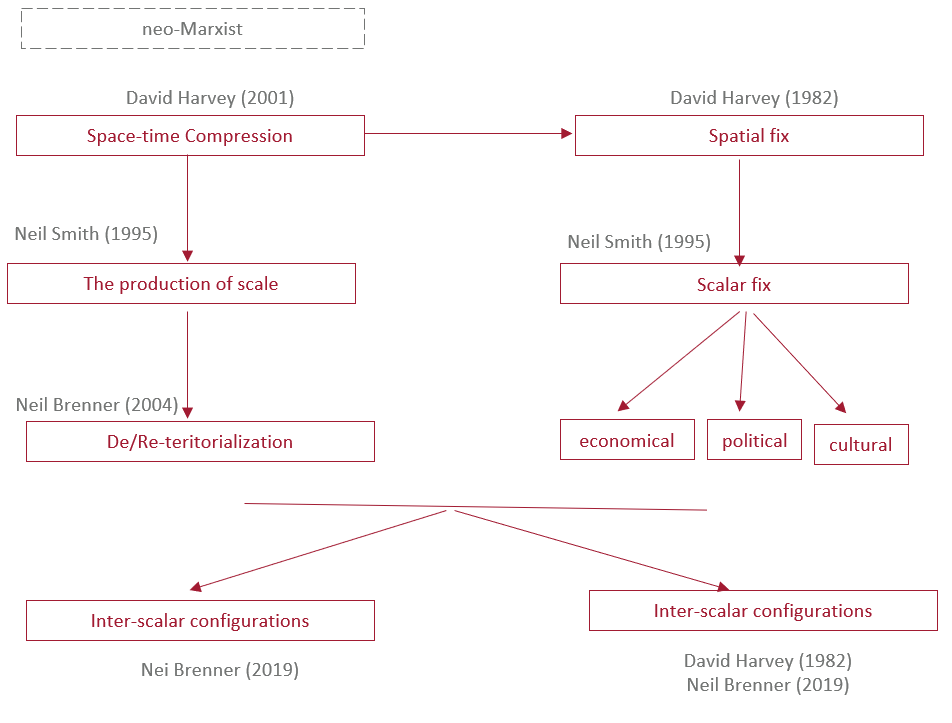

The compression of space-time (Harvey 2001) is the spatial organization is necessary to overcome space, the conversion of temporal into spatial restrictions in accumulation.

Spatial fixation (Harvey, 1982) is a tendency towards a structured coherence of production and consumption in a given space: (1) the relatively stable, long-term nature of the investments that are embedded in the built environment and the infrastructure associated with these configurations; (2) the immobilized nature of those investments; and (3) their role as a potential resolution to capital’s crisis tendencies, albeit one that is strictly circumscribed in both temporal and spatial terms.

Scale fix (Smith, 1995): Geographical scale can be fixed or fluid. Newly established scales of social interaction establish fixed geographic structures that delimit political, economic, and cultural activity in specific ways; highly contested and contested social relations become anchored, if not set in stone, at least in landscapes that are, in the short term, fixed. In geography, political difference is fossilized, as it were, naturalizing entire realms of contestable social organization.

The production of geographic scale (Smith, 1995) is a highly charged and political process, as is the ongoing reproduction of scale (eg, the defence of national borders, a community’s tax base, regional identity). Even more politically charged is the reproduction of the scale at different levels – the restructuring of the scale, the establishment of new “fixings of the scale” for new forms of concatenations of political, economic and cultural exchanges.

- Economic production of scale (Smith, 1995). While the local scale can be conceived as expressing the geographical range of daily reproductive activities (e.g. commuting to work) and the regional scale as a subnational expression of the geographical coherence (or otherwise) of production systems distinct, the extent of the nation-state rather springs from the global circulation of capital. With the internationalization of commercial capital in the 17th and 18th centuries, the problem of coordinating competitive and cooperative relations between capital holders became increasingly vital. The nationalization of capital, simultaneously with and as part of the internationalization of capital, was the historical solution.

- The political production of scale (Smith, 1995): It would be a mistake to overgeneralize and assume a complete congruence of political and economic interests. From the American Civil War and the Paris Commune to the fate of the Habsburg Empire and the failures of the Versailles Peace, there are abundant illustrations of the imprecise alignment of economic and political interests in the geographic territorialization of the nation-state. These struggles took place along class and race lines or resulted from intra-class conflicts. But as intense as these struggles were, they did not prevent the emergence of the nation-state as a geographical scale and as an adequate political vehicle for arbitrating the division of capital.

- Cultural scale production (Smith, 1995): Scale production is also a cultural event. Individual and group identities are strongly coloured by attachments for which they can be placed on different scales. On a national scale, nation-states can be an expression of the competition between capitals in the world market, generated, defended, and expanded by military as well as political and economic means, but they also involve the creation of extraordinarily deep identities. Nationalism is a cultural and ideological force, which helps to sculpt the spatialization of social relations from the beginning, and which is sometimes a decisive force in any restructuring of scale.

Re-/De- territorialization (Brenner, 2004): Capital tends to remove geographical barriers to accumulation in search of cheaper raw materials, new sources of labour, new markets for its products, new investment opportunities

- Deterritorialization: Capital tends to remove geographical barriers to accumulation in search of cheaper raw materials, new sources of labour, new markets for its products, new investment opportunities. Capital is simultaneously oriented towards temporal acceleration (the continuous reduction of the time in which profit is made) and spatial extension (overcoming geographical barriers in the process of accumulation). These spatio-temporal trends in capital relations produce processes of ‘spatio-temporal compression’.

- Re-territorialization (Brenner, 2004): Reducing the socially necessary time for the production of profit and the impulse to expand space are both dependent on the production of a relatively fixed and immovable socio-spatial configuration. Spatio-temporal compression processes can only take place through the production of socio-geographical infrastructure specific to a historical time, for example, the built urban environment, industrial agglomerations, regional production complexes, collective consumption systems, extensive transport networks, communication over long distances, regulatory state institutions.

Inter-scale configurations (Brenner, 2019): Capitalist territorial organization is scaled within historically specific inter-scale configurations, “hierarchical structures of organization” that provide provisional stability in the maelstrom of socio-spatial creative destruction. The resulting scale configurations, or scale corrections, are essential organizational and operational elements within each spatial correction. Spatial fixations are not only embedded in pre-existing spatial scales or positioned on a fixed scalar scale, but involve the construction of inter-scale hierarchies, specific to the division of labor, patterns of stratification, relays, circuits and operations in support of capital accumulation.

Inter-scale dynamics (Harvey vs. Brenner):

- Harvey (1982): In times of crisis, the tension between fixity and movement breaks down, and thus nested hierarchical structures of organization across scales are reorganized, rationalized, and reformed. Overstretched institutional arrangements are brought into closer relationship with the underlying demands of accumulation. to serve to absorb over-accumulation and avoid the threat of devaluation.

Brenner (2019): Scale corrections are produced through the politically negotiated, often accidental, merging or “weaving” of multiple socio-spatial relations, projects and struggles. The correction of salts in territorial organization is not only caught in the fixity/movement contradiction, but is at the same time an arena, a stake and a product of sociopolitical conflict. Rescaling is, in this sense, a political strategy.

Content:

Regional trajectories: The behaviour and performance of firms are firmly rooted in a regional knowledge resource base and a particular institutional framework, which are durable and irreversible. Both region-specific assets provide incentives and set constraints within which the innovation process takes place. In this sense, the region, functioning as a selection device, is an independent entity. The region consists of a variety of firms in a technology field that have differentiated themselves by utilizing unique regional resources. Firms come and go without affecting the region’s knowledge and skills base and its institutional framework and thus its level of competitiveness. Therefore, it is not the individual or organizations that matter, but the territorial level. Regional development is therefore path-dependent: a region moves along a specific development trajectory that affects the types of skills most developed, how the institutional set-up co-evolves and influences production, learning and innovation.

Regional competition: Weak competition (week) means static price competition. Regions may pursue a strategy that focuses on relatively low labor costs or exploit institutional differences between regions (such as differences in subsidies or labor regulation systems) that directly affect price competition among firms. A strong (hard) regional competition strategy based primarily on the exploitation of the “soft” (eg identity, culture, institutions), intangible, region-specific assets described above is likely to be more effective in the long term. Policymakers, however, should be reluctant to imitate a successful (institutional) model (such as the Silicon Valley model) that originates in a different environment without considering the contexts specific to the region. There is no optimal model in evolutionary thinking, and therefore benchmarking studies are unlikely to reveal one.

- Socio-technical regime: coherent complex of scientific knowledge, engineering practices, production process technologies, product characteristics, skills and procedures, established user needs, regulatory requirements, institutions and infrastructures.

- Niche: New paths emerge from the strategic actions of heterogeneous groups of actors who collaborate on stuck structures and mobilize resources to create a new industry.

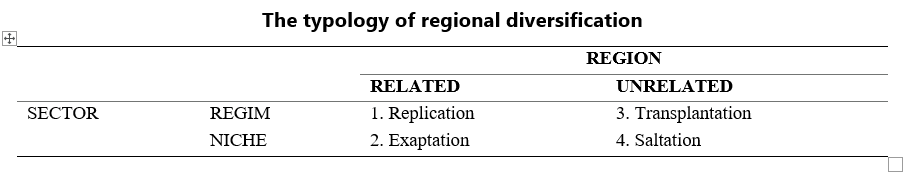

Related diversification: Existing local capabilities condition which new activities are more likely to develop in a region or country. Similarity is an important driver of regional diversification, even though studies use different dependent variables (such as new products, industries, technologies), similarity (e.g., similarity between products, technological, skills, inputs-outputs), spatial units of analysis (countries, regions, cities, labor market areas) and time periods.

Unrelated diversification: The more a new industry is unrelated to the capability base already built in the region, the more a new industry marks a radical departure from a region’s own past. Distinct (unrelated) diversification occurs when a region develops a new activity that requires very different capabilities from existing local activities and therefore tends to be led by actors who have consolidated their capabilities elsewhere (migrated, multinationals) and in some cases were supported by state policies. Alternatively, distinct diversification may arise from within the region through the recombination of previously unrelated technologies.

There can be four types of regional diversification. The related diversification of a region can be of two types: related and unrelated. Socio-technically this diversification can be based on the reproduction of a regime or on the creation of a new regime:

- replication within an existing global socio-technical regime

- exaptation by creating a niche that can develop into a new global regime.

- transplantation involves a change in the regional capacity base, but within the limits of the existing socio-technical regime,

- while salting represents the most radical type of regional diversification, which requires not only a transformation of regional capabilities, but also a complete regime change.

References

- Boschma, Ron (2016): Relatedness as driver of regional diversification: a research agenda, Regional Studies, 51(3): 351-364.

- Boschma, Ron, 2004. Competitiveness of Regions from an Evolutionary Perspective, Regional Studies, 38(9), 1001-1014, pp.1003.

- Boschma, Ron, Lars Coenen, Koen Frenken & Bernhard Truffer, 2017. Towards a theory of regional diversification: combining insights from Evolutionary Economic, Geography and Transition Studies, Regional Studies, 51(1):31-45

- Brenner, Neil, 2004. New State Spaces: Urban Governance and the Rescaling of Statehood, Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press

- Brenner, Neil, 2019. New Urban Spaces: Urban Theory and the Scale Question, p.60. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press.

- Harvey, David, 1982. Limits to Capital. London: Verso.

- Harvey, David, 2001. Geopolitics of Capitalism, Spaces of Capital: Towards a Critical Geography. London & New York: Taylor & Francis

- Smith, Neil, 1995. Remaking Scale: Competition and Cooperation in Pre-national and Post-national Europe. In: Eskelinen H., Snickars F. (eds) Competitive European Peripheries. Advances in Spatial Science, pp. 59-74. Berlin & Heidelberg: Springer.

Other Instructors

Florin FAJE

Lecturer

Cristian POP

Lecturer

Norbert PETROVICI

Associate Professor

Anca CHIȘ

Communication specialist

Ionuț FÖLDES

Lecturer

Syllabus

The aim of this class is to make students familiar with the concept of regions in two distinct traditions: of the institutionalist approach of the Evolutionary Economic Geography (Boschma, 2004) and of the Region as a Spatial fix for Capital Accumulation (Smith, 1995). While these two traditions of Regional Comparative Political Economy overlap, the paradigmatical underpinnings are starkly different, the first being Durkheimian, the second being Marxist. The implication are quite different for research, and the empirical enquiries rooted in the two traditions describe the European regional dynamic quite differently. In this class the accent will be on the research papers that problematizes European political economy at regional level.

O1.M1 UNDERSTANDING THE TERRITORY AS A SYSTEM

O1.M1.07 The political economy of regions in Europe

Type of format

Lecture & Workshop

Duration

Session 1 – 45 min: The concept of region in EU 30 min lecture on the foundations of the administrative division and hierarchies of region in Europe 15 min discussion with the participants regarding the main traits of a regions as an entity with agency, yet constrained by path dependences Session 2 – 90 min: Conceptualizing varieties at regional level in EU 30 min lecture on presenting the varieties of capitalism framework for defining the regions: the dominant paradigm of Evolutionary Economic Geography. 30 min lecture on presenting the knowledge underpinning of region and the central concept of spill-overs. 10 min break 20 min workshop – opening a geographical file with the regions in EU based on Eurostat classifications. Session 3 – 90 min: The region as a geographical scale 40 min lecture on presenting the de-/re-territorialization of capital framework for defining the regions. 20 min for presenting research and visualization of geographical scales: urban, regional, and national global 10 min break 20 min for preparing a list of interdependencies between a given region and the rest of the scales (in groups of students) Session 4 – 90 min: Regional competition and growth 20 min introductory lecture on the economic growth at regional level 40 min workshop on competition and cooperation among regions in EU 10 min break 20 min final discussion

Possible connections (with other schools / presented topics)

UAUIM O1.UAUIM 01 / Grid and border as instruments of planning and criticism in architecture SUSKO O1.M2.02 Introduction to GIS Story Maps

Main purpose & objectives

The main purpose of this class is to make students familiar with both the concept of region in EU and with the administrative definitions at EU level. The first objective is to master the basic concepts describing the regions. The second one is to provide the GIS delimitation of the NUTS and understand the keys necessary to connect to the geographical files. The third objective is to master the main variables used in research to describe the trajectory of a region, the cooperation and competition between regions.

Skills acquired

Basic knowledge required to understand EU regions. The ability to use GIS tools to connect to geographical files. Picking the appropriate conceptual language to describe a region. Learning how to discern valuable and useful empirical material describing the region.

Contents and teaching methods

All of the above-mentioned sessions will be based on a dynamic combination of lectures with a hands-on approach in the several workshops for each topic.

Reviews

Lorem Ipsn gravida nibh vel velit auctor aliquet. Aenean sollicitudin, lorem quis bibendum auci elit consequat ipsutis sem nibh id elit. Duis sed odio sit amet nibh vulputate cursus a sit amet mauris. Morbi accumsan ipsum velit. Nam nec tellus a odio tincidunt auctor a ornare odio. Sed non mauris vitae erat consequat auctor eu in elit.

Members

Lorem Ipsn gravida nibh vel velit auctor aliquet. Aenean sollicitudin, lorem quis bibendum auci elit consequat ipsutis sem nibh id elit. Duis sed odio sit amet nibh vulputate cursus a sit amet mauris. Morbi accumsan ipsum velit. Nam nec tellus a odio tincidunt auctor a ornare odio. Sed non mauris vitae erat consequat auctor eu in elit.